Lynch-Mobbery Isn’t Going To Be Solved By A New Law; It Needs Deeper Police And Legal Reforms

Reform of the police-legal-judicial system is the key to ending vigilantism, and not legislating tougher and tougher laws, as this will not bring about deterrence or compliance by a people who feel cheated by the law and order machinery.

If one were to look at the Supreme Court’s orders on mob violence and lynching, the short-term remedies suggested by the bench are unexceptionable: asking states to designate officers of the rank of superintendent of police in each district to prevent mob violence is something states ought to have done themselves; sending messages of warnings on TV and mass media that lynching will have serious consequences for those involved is an obvious thing to do; compulsory filing of FIRs and setting up of fast-track courts to deliver verdicts in six months ought to be the norm for almost any serious crime; and compensating victims does not need reiteration.

The three-judge bench, which had Chief Justice Dipak Misra, Justice A M Khanwilkar and Justice D Y Chandrachud as its members, also sought compliance reports from states within a time-frame and – as a long-term measure - asked for a new law specifically focused on preventing and prosecuting mob violence.

The problem with the court’s order stems not from its intent, but two related weaknesses: no law can be administered and overseen purely through court interventions in the long run; and having more and more stringent laws to deal with specific crimes will ultimately defeat the purpose of having a polity that respects the law. If every crime needs special laws and draconian powers for enforcement – whether it is dowry, or domestic violence, or atrocities against Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, or mob violence – ordinary laws meant to prevent crime will lose their meaning. It will be an admission that only giving draconian powers to law enforcement officers can we maintain law and order. And giving any arm of government draconian powers will result in state-led crimes and corruption.

What the Supreme Court has essentially suggested is that the law and order machinery in states and Centre has essentially crumbled, and that there is no way citizens can get fair treatment or justice except through direct monitoring by courts and special laws. Since the Supreme Court or even the high courts cannot become watchdogs on law and order in every state and in every case, ultimately we are not going to obtain compliance.

The record of non-compliance on a host of Supreme Court directives is indicative of this:

- A Supreme Court order on the demolition of illegal religious structures in public spaces is still to be complied with, even after various benches have threatened state officials with contempt and action. The first order in this case dates back to 2009.

- A Supreme Court verdict in 2012 against the Sahara group has gone unimplemented to this day despite repeated incarceration of Sahara boss Subrata Roy.

- In 2016, the Karnataka government defied the orders of the top court to release water to Tamil Nadu, after then Chief Minister Siddaramaiah used his legislature to back his defiance.

- The Supreme Court, in a major verdict in 2006 (Prakash Singh versus Union of India) ordered police reforms to be implemented so that there is greater professionalism and less political interference in their working. But to date many elements of its orders remain unimplemented – in spirit if not in law. No less a person that the last Chief Justice, J S Khehar, when confronted with yet another petition demanding implementation of reforms, threw up his hands and said: “Nobody listens to our orders.”

The lesson for the courts is this: you cannot deliver justice all on your own, and making more and more interventions, instead of merely in those cases with the biggest impact, will undercut the judicial system’s own credibility and authority in the long run.

Lynching and mob violence will not go away until and unless the basic laws on crime are enforced through normal laws. These are symptoms that the law and order and legal systems are not working as they should, and till this is fixed, people and motivated groups will take the law in their own hands, never mind what the Supreme Court thinks of them. If there is only one key reform the court should supervise till its logical end, it should be this one.

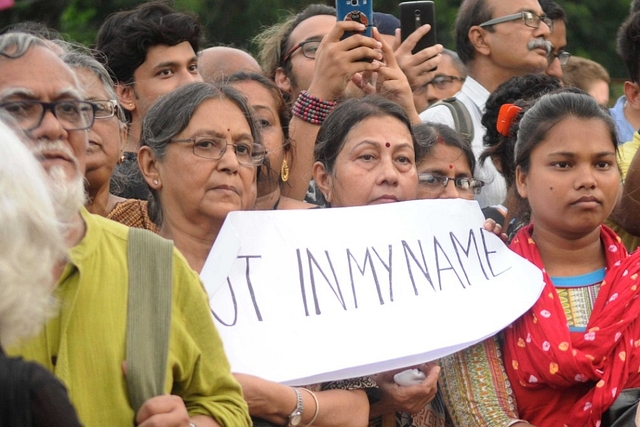

The media must take its share of the blame in making our laws worse than they need be. Attempts to paint lynch-mobs as purely a Hindutva phenomenon are wrong-headed and possibly partisan, as it divides law-makers on political lines when what we need is a consensus. The recent bouts of mob-lynching based on WhatsApp rumours about child-lifting prove that lynching is the result of an absence of the law when crimes get committed, and not related to only one group of people. Sure, there is cow vigilantism and lynching related to cow smuggling, but this, once again, represents the failure of states to implement their own laws on the cow slaughter ban. Either they must have the courage to modify these laws or create a regular law and order machinery to implement them. If you don’t implement your own law, someone else will – to the ultimate detriment of everybody’s interests. In fact, the emergence of TV channels with the same vigilante mentality is evidence that lynch-mobbery has gone mainstream – even if this lynching is verbal rather than physical.

Media on both sides of the Narendra Modi/BJP divide are pandering to this latent lynch-mob mentality in society by behaving in a partisan way – where the same crime is viewed with different lenses depending on your political inclinations.

Two simple conclusions emerge from the above discussion.

First, reform of the police-legal-judicial system is the key to ending vigilantism. You can keep legislating tougher and tougher laws for the same crime, but you are not going to get deterrence or compliance by a people who feel cheated by the law and order machinery. The only right way to go about it is by making the police leadership professional and insulated from political pressures, so that they can do their jobs as the law mandates them to. A judicial system, including one which fast-tracks cases, is not good enough on its own without a reform of legal and criminal processes and proceedings. It is worth noting that in the Nirbhaya (Jyoti Singh) case, which was decided by a “fast-track” court, the Supreme Court has only now confirmed the death sentences on the accused. And there is one more appeal left, and after that the President still has the right to pardon and commute the sentence. This kind of judicial process cannot deliver closure to victims, and today Jyoti Singh’s mother wants the rapists burnt alive as a form of retribution for the brutality her daughter was subjected to. We would call this a lynch-mob mentality if we did not know who she was, and how she has suffered.

Second, making laws work is not something the judiciary can impose or even supervise from above. Effective law comes from a joint commitment on the part of both law-makers and the judiciary to work together to achieve this end, with additional support coming from saner elements of civil society. No politician will ultimately implement what he does not believe is worth doing in his political interests. And civil society does not mean those activists who are verbal lynch-mobs of one kind or the other, whether they are mindless feminists, or human rights activists whose hearts only bleed for Maoists, or free-speech advocates who want only one kind of free speech – the kind they support. It is moderate elements in civil society who need to drive this change, not IYIs (intellectual yet idiot) activists. (IYI is a phrase popularised by Nassim Nicholas Taleb). India’s is a wounded society with many raw and unhealed wounds on its body politic, and slow but steady change towards a more liberal but law-abiding society is what is required. India’s “liberals” repeatedly make the sensible the enemy of the ideal, thus making progress twice as tough.

More than yet another tough law to handle just lynch-mobs or child rapists, we need to start the long and arduous process of changing mindsets through education, media campaigns, and a law and order machinery that begins to work for the people than against them.

Postscript: Even as the Supreme Court was telling us that mob violence cannot be the “new normal”, lawyers in Chennai were busy roughing up 17 people accused of repeatedly raping a 12-year-old girl over months. When people who know the law act like lynch-mobs, we know that a new law alone is not going to solve the problems of mob violence.