Modi 2.0 Reset: A Shift From Distrust Of Business To “Trust, But Verify” Mode

In the UPA era, the trust factor with business was higher simply because it was based on a share-of-the-spoils concept.

But somewhere along the Modi government line, the fear of being labelled a suit-boot-ki-sarkar forced the establishment to keep businessmen at arm’s length.

Budget 2020-21 signals is a shift.

The Narendra Modi government has come half circle in terms of its relationship with citizens, businesspersons and traders.

In the first term, the government's theme song was black-money reduction, tax-compliance and an end to cronyism.

The net result was a gradual expansion of the extractive state, where “tax terrorism” was being whispered louder than before. The fallout was growing mistrust.

But the government has realised that the growing mistrust between government and business has gone too far, and, in the last two budgets, and even in his last Independence-Day speech, Modi made respect for “wealth creators” his new catchphrase.

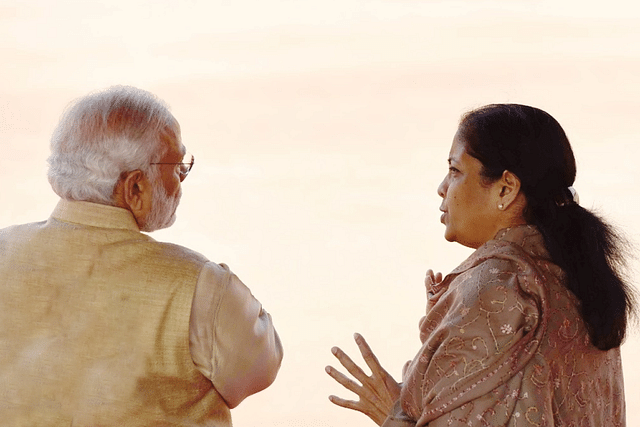

In both the latest Economic Survey and Nirmala Sitharaman’s 2020-21 budget speech on 1 February, there is a new emphasis on “trust”.

While the Survey’s very first chapter talks of the need for the “invisible hand” of the markets to be backed by “the hand of trust” in order to enhance wealth creation, the budget makes several references to trust — in citizens, taxpayers, small businesses, et al.

The Survey noted: “India’s aspiration to become a $5 trillion economy depends critically on strengthening the invisible hand of markets together with the hand of trust that can support markets. The invisible hand needs to be strengthened by promoting pro-business policies to (i) provide equal opportunities for new entrants, enable fair competition and ease doing business, (ii) eliminate policies that undermine markets through government intervention even where it is not necessary, (iii) enable trade for job creation, and (iv) efficiently scale up the banking sector to be proportionate to the size of the Indian economy.”

It emphasises the need for “introducing the idea of trust as a public good that gets enhanced with greater use.”

The idealistic tone of the Survey, of course, is difficult to implement in a diverse society where mistrust is writ large — not only between government and public or business, but also between various segments of the public.

This is why various governments have found it so hard to pursue factor market reforms or effective welfarism.

They have preferred to take the fiscally ruinous route of offering voters freebies and “private goods” as opposed to public goods like better law and order, good roads, schools and hospitals.

Excess diversity militates against trust, which is, perhaps, why the Modi government has opted for the more nuanced and practical idea of moving towards “trust” with a caveat: offering trust as long as it is possible to verify that the trust is not being betrayed.

In the UPA era, the trust factor with business was higher simply because it was based on a share-of-the-spoils concept.

Just as there is honour among thieves, there is a fair amount of trust in the state as long as it allows various categories of people to loot it on the sly.

This trust based on loot-and-scoot existed not only between government and business, but also between state and citizens, as politicians played middlemen to obtain benefits for favoured voters both at the time of elections, and afterwards.

If you want a water connection, it comes not as a right, but as a result of your politician’s ability to deliver the benefit as a special favour.

Under Modi, this system of trust based on share-of-spoils and cronyism has been upended, resulting in increasing mistrust.

This was worsened by the Prime Minister’s concern with his image, and avoiding the label of “suit-boot-ki-sarkar”.

In trying to prove his pro-poor credentials, Modi effectively kept all businessmen at arm’s length in his first term and never got to hear about their genuine pain and problems.

Modi 2.0 has course-corrected now. The new watchwords are about building trust cautiously, ie, “trust, but verify.”

This is the essential reset that has happened without anyone acknowledging it openly.

In his last term, Modi extended the “trust, but verify” concept to various subsidy schemes by making direct benefits transfers transparent as long as they were Aadhaar-authenticated.

He thus reduced leakages and improved trust among beneficiaries.

This time, this same idea is being extended to small businesses as well. Consider what Sitharaman said in her speech: “Currently, businesses having turnover of more than one crore rupees are required to get their books of accounts audited by an accountant. In order to reduce the compliance burden on small retailers, traders and shopkeepers who comprise the MSME sector, I propose to raise by five times the turnover threshold for audit from the existing Rs 1 crore to Rs 5 crore. Further, in order to boost the less-cash economy, I propose that the increased limit shall apply only to those businesses which carry out less than 5 per cent of their business transactions in cash.”

This is a classic “trust, but verify” position. The government is essentially offering small businesses the right to avoid compulsory auditing of accounts only if they do their business in non-cash ways.

In short, no need for an audit, if you anyway create a financial trail for your business transactions that the taxman can verify.

In many ways, Modi’s enthusiasm for the Goods and Services Tax (GST) flowed from the same “trust, but verify” thought process. Under GST, compliance is ensured by the buyer of an intermediary product getting input tax credits only if the seller has paid his own taxes.

In short, the buyer is the verifier on behalf of the government, ensuring compliance. While the GST is far from reaching its ideal state, it is a “trust, but verify” scheme.

Then there is the amnesty-but-not-quite-an-amnesty scheme announced in the budget — which again marks a shift from the mistrustful amnesty schemes of Modi 1.0.

The three black money amnesty schemes announced in Modi 1.0 in 2015 and 2016 were about telling businessmen that since you are crooks, you should be penalised heavily even for seeking amnesty.

These schemes were largely flops, with very little of India’s back wealth emerging from the woodwork.

But there is clearly a rethink now. The Finance Minister said in her speech: “In the past, our government has taken several measures to reduce tax litigations. In the last budget, Sabka Vishwas Scheme was brought in to reduce litigation in indirect taxes. It resulted in settling over 189,000 cases. Currently, there are 483,000 direct tax cases pending in various appellate forums...This year, I propose to bring a scheme similar to the indirect tax Sabka Vishwas for reducing litigation even in the direct taxes. Under the proposed ‘Vivad Se Vishwas’ scheme, a taxpayer would be required to pay only the amount of the disputed taxes and will get complete waiver of interest and penalty provided he pays by 31 March, 2020. Those who avail this scheme after 31 March, 2020 will have to pay some additional amount. The scheme will remain open till 30 June 2020.”

This again is a variant of the “trust, but verify” idea. In effect, the FM is saying ‘I won’t harass you and involve you in endless litigation if you pay up at least what we demanded earlier’.

For taxpayers with small demands that have bloated to large amounts due to the accrual of interest and penalties, this could well be worth the taxes paid. The tax dues of, say, 2010, have now been shrunk by the effects of inflation.

What budget 2020-21 signals is a shift from mistrust to not trust, but a region of intermediate trust, where trust can be earned by doing the right things. This is the “trust, but verify” phase of India’s evolution into a more tax-compliant society.