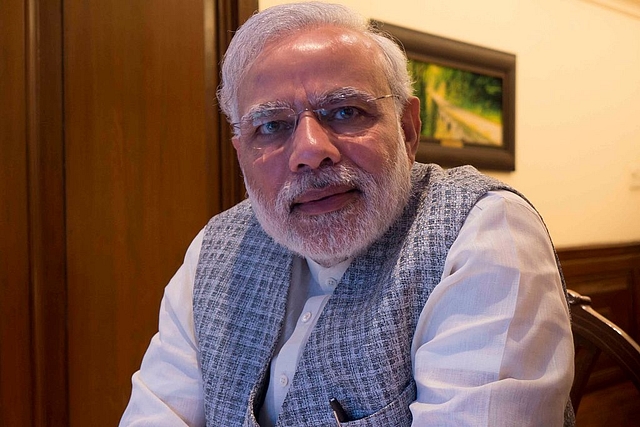

Narendra Modi: The Person, The Politician And His Penchant For Progressiveness

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has with his distinct ways raised the bar for governance, conduct of foreign policy and financial reforms.

A glance into the three-and-a-half-years of Modi government.

Narendra Damodardas Modi has now been India’s Prime Minister for three and a half years. Before that, he was the chief minister of Gujarat for a little over 12 years. He won three successive elections there, and since becoming Prime Minister, he has led his party to several electoral victories, the most notable being the one in Uttar Pradesh in March this year and Jammu and Kashmir in 2016.

Apart from electoral victories, Modi is also slowly – some would say too slowly – transforming some aspects of the way in which India is administered. He has also brought about a sea change in the way it is governed, most notably in Kashmir where he has adopted an uncompromisingly tough stand vis a vis the separatists.

His most outstanding success has come in foreign policy where he has managed to stare down China which had tried to occupy Bhutanese territory in the Doklam plateau. India is treaty bound to defend Bhutan. Modi’s unexpected firmness has taken China by surprise, which had been threatening to attack India. Of course, it may still do that.

There are many other less visible successes Modi has notched up such as focusing the country’s attention on the empowerment of women via the triple talaq issue; the Swachch Bharat campaign; the direct benefits transfer initiative; and few others. There has also been some movement on ease of business initiatives, overall administrative reform and reducing the size of the state.

The Man’s Mind

It is useful, in this overall background, to ask: how does his mind work? How does he cope with crises? What lies behind his mental resilience and approach? This article is a small effort to answer some of these questions.

First and foremost, Modi takes his cues from Hindu scriptures when confronted with challenges. This has given him a formula, as it were, in his emphasis on taking a problem and turning it around to make it an opportunity. That is how he turned around the 2001 earthquake narrative: his narrative was that he had done outstanding relief work and thus taking the focus away from the disaster as well as the previous administration’s inefficient response, instead of focusing on his management skills.

Another example – and not the only other one – can be found in 2012 when the opposition in Gujarat kept saying he had 250 kurtas. Realising there was little to be gained from countering such fabrications he simply turned the narrative around, retorting that that was far better than having a son-in-law who had Rs 250 crore in ill-gotten wealth. He thus managed to highlight his clean image and the complete absence of nepotism in his working.

He is also an expert in taking very calculated risks. In Gujarat, he clamped down on electricity theft with some very tough measures such as jail for farmers and others who were found stealing electricity. This was somewhat of a gamble for him, as it took on the powerful farmer constituency. But Modi knew it was the lack of electricity that bothered farmers, not paying for it. Farmers were happy to pay for a reliable supply. Another illustration of this was when he used to berate his voters telling them if their cities were so filthy, how could he invite international guests to Gujarat?

He also lays a great deal of store by Indic principles that emphasise ideas of cordiality. His invitation to South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) heads of government wasn’t an impulsive one. He had thought it through. His first instinct is to try and resolve a problem via tact and prudence. It is only when these fail that he turns on the pressure. He more-or-less said so recently while addressing CEOs. If people had paid heed to my entreaties to pay tax honestly, he said, 8 November would not have happened referring to the day demonetisation was announced.

Another characteristic is his inclination to listen to as many people as possible and understand what they are trying to put across to him with utter concentration. But having heard them out, he acts entirely from the prism of his experience and worldview. But he generally meets those who come recommended. His operating principle is “the king must only meet someone who is introduced by an acquaintance”.

His general method of reducing discretionary powers of government is using information technology and automation. So in Gujarat part of the driving licence test was computer based, thus reducing government’s discretionary powers. As he animatedly explained to people, “If the RTO test sahib was in a disagreeable mood, he was likely to flunk the candidate; now with computerised testing that was not possible”

He has deep respect for dignity of the human person. So once at a graduation ceremony, he pointed out that the success the students had achieved was also in part due to people such as sweepers or domestic help or anyone who helped smooth out their lives – a politician trying to get his middle class audience to become grateful to all the contributors of society, in our status-driven world was poignant. He also encouraged newlyweds and state transport bus drivers to study further, so that they could achieve their fullest potential.

The environment is also something that animates him passionately. He would gently persuade people to plant trees. If they found watering the plants every day tiresome, he had a solution for that too – all they needed to do was place an earthen pot filled with water next to the tree and by drip irrigation the tree would be water-fed. Or of conserving water via using drip irrigation, in farming.

He is certainly not an elitist. So in Gujarat he would say “When more people use rail stations, why should they not be as good as airports?” With the new Ahmadabad and Surat bus stations in Gujarat, he kept his promise. They don’t look anything like the decrepit infrastructure of old-socialist India. It was excellence in infrastructure which he broadly aimed for

His enduring love of learning came through in various ways – his suggestion to architects to have a little corner for a library in every house, to remind people to read. Or when at the Ahmedabad book fair, he appealed to Gujaratis to revere Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge just as they revere worship Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth.

In a more lighthearted vein, he also suggested that whilst evaluating potential suitors for marriage, just ask them what they read, if they are well read, that was a sort of guarantee of a good upbringing and values, one need not ask for any more references.

He is also a trifle self-deprecating. In Gujarat once, he gently rebuked his hosts who had invited him to the inauguration of a new temple in Sabalpur, in north Gujarat. His hosts said the ground which the chief minister had walked on had become sacred, to which he offered a sardonic riposte. He told them how as a boy he travelled on this same land, often to buy vegetables, so what was so different now?

Once he also pardoned a Muslim who threatened him and in fact invited him for dinner with his parents.

The author was associated with political communication for Narendra Modi when he was chief minister of Gujarat.