Raghuram Rajan’s Missing ‘Third Pillar’ Thesis Is Applicable To West, Not India

Rajan’s remedy of civic nationalism is something that cannot be mandated by law or imposed from above; it has to evolve by choice once the state and markets become stronger relative to community.

Rather than trying to create artificial communities defined by civic nationalism, the focus should be on strengthening the state, its institutions, and the markets.

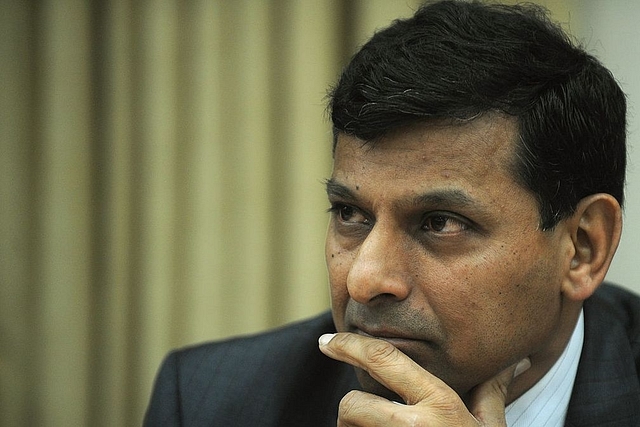

In his latest book, The Third Pillar, former Reserve Bank governor Raghuram Rajan talks about economics’ blind spot. The focus of research has been on the relationship between the state and the markets, while community has been ignored. As a social science, economics cannot ignore the societal aspects that are critical to development, progress, equity and justice.

Rajan makes the case that the crisis of confidence in capitalism in the west flows largely from the fact that state and markets have grown too powerful at the cost of the “third pillar” – strong communities. Strong communities are vital if the benefits of state and markets are to be taken advantage of by people in general in order to lift themselves up.

Rajan’s hypothesis, that community is the weak pillar in the west, cannot easily be applied to a country like India, where community networks of caste, religion and language are strong. In fact, one can argue that India’s problem is the exact opposite of that of the west, a super-strong community that overawes the state and markets.

Our democracy has been hijacked by vested community interests who do block voting and try and capture the state and its institutions in order to direct state resources towards specific communities. Once some castes and religious groups come to power, they use state power to suborn its institutions, from the police to parts of the judiciary to even some state corporations and regulators. At another level, crony capitalists capture the loyalties of caste-based politicians and parties by giving them electoral funding. They enter into cosy deals to capture markets and tilt regulations in their favour to the detriment of the rule of law and citizen and consumer interests. Thus, both state and markets are subverted by strong communities.

In India’s first-past-the-post electoral system (FPTP), it takes barely 30-and-odd per cent of the popular vote in multi-party contests for anyone to win a majority of seats. This means the rulers are beholden to a minority of voters. Why then would they strengthen state and markets to reflect a neutrality between competing interests? Why would they invest in public goods like law and order, schools and hospitals, and not gift freebies to their specific voters? In India, no party has any interest in doing so. The combination of FPTP and strong communities ensures that neither state nor market is strong.

Whether it is cow-related lynchings or shows of violent strength by various caste and community groups (Dalits, Jats, Muslims, et al), communities tend to overawe the state. Many states ban cow slaughter in order to respect popular Hindu sentiments on this, but they simply do not have the resources or even the inclination to enforce their own laws. Thus, this job then gets illegally outsourced to assorted vigilante groups, who may use this as an opportunity to collect protection money or indulge in violence. When a violent Muslim mob torches a police station in Kaliachak in West Bengal, the state quietly repairs the damage instead of asserting itself and calling out the miscreants. Community trumps law and state.

We know how the CBI has been called a caged parrot, but we also know that the local state police act like the power arm of the ruling party. In a recent bid by the CBI to question a Kolkata police officer, the state police obstructed its efforts. Even assuming the entire CBI effort was politically motivated, there is little doubt that the West Bengal police acted on behalf of its political masters and not as per law and protocol. And it isn’t as if the judiciary itself has not been compromised. In 2010, lawyer Shanti Bhushan made an open allegation in the Supreme Court that eight of the previous 16 chief justices were corrupt, but the court did not act on this allegation. And the evidence is that the selection of judges to the higher judiciary is non-transparent. An Indian Express report from 2012 noted that of the 21 Supreme Court judges who retired in the previous four years, 18 were given post-retirement sinecures by the United Progressive Alliance government. A judiciary that seems on a wink-and-a-nod relationship with the executive cannot protect the citizen when the state intrudes into his privacy and tramples over his rights.

As for markets, the less said the better. One reason why the farm sector – the largest in terms of people dependent on it – is in distress is the refusal of politicians to let the markets work in favour of the farmer. The agriculture market is rigged to suit the vested interests and middlemen. As for the non-farm markets, it is only now that cronyism is being addressed, and market capture by monopoly interests is facing some restraint. But the job of freeing markets from the clutches of cronies and politicians is far from over.

By Rajan’s definition, two of the three pillars – state and markets – are weak. But in India’s case, he would probably be equally cautious about the strength of communities, which tend not to be inclusive and may sometimes privilege narrow nationalism. In his idealistic view, the exclusionary nature of community groups which represent narrow nationalism should be replaced by a form of “civic nationalism”, where communities remain communities only in the social sphere, but become one when they interact with state and markets. This, of course, is not going to happen anytime soon as long as our electoral system privileges a re-emphasis on caste and community.

There is a mistaken notion, often propounded by opponents of the Narendra Modi government, that the state has become all-powerful under a single-party majority government. This is questionable, for the state is not the same as an individual who has become powerful for various reasons, including charisma, high personal popularity and a parliamentary majority. Such individuals come and go, but the state remains. A strong state is strong despite the rise of strong individuals like Modi. So, it is wrong to presume we have a strong state just because Modi may be a strong leader. We need a strong but limited state where institutions protect the individuals from the excesses of the state, and the state can uphold the rule of law against recalcitrant individuals.

The other myth is that Modi is destroying institutions. The truth is somewhere in-between. Not giving the CBI freedom to operate as an independent institution or sitting tight on embarrassing NSSO jobs data can weaken these institutions, but one must also add up the positives. One of the first things the Modi government did was put in place a more transparent mechanism, the National Judicial Appointments Commission, for judicial selection, but the Supreme Court nixed that. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code is a key weapon to cut crony capitalists down to size and rebalance the lender-borrower equation. This will make the exit of incompetent managements better.

Rajan’s remedy of civic nationalism is something that cannot be mandated by law or imposed from above; it has to evolve by choice once the state and markets become stronger relative to community. Rather than trying to create artificial communities defined by civic nationalism, the focus should be on strengthening the state, its institutions, and the markets.

This is India’s challenge No 1.