Should Political Parties Be Subjected To The RTI Act?

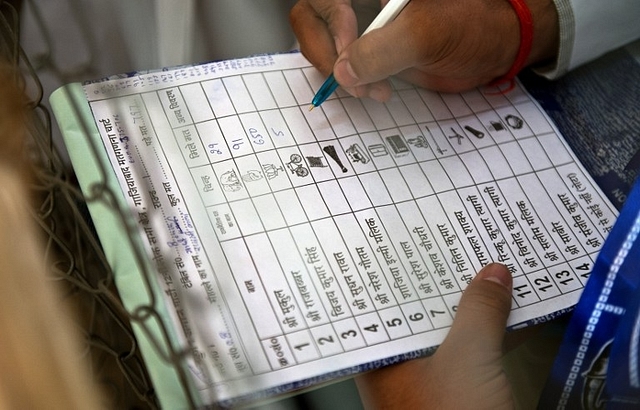

The very recent affidavit filed by the Centre before the Supreme Court on its concerns in subjecting all the political parties to the Right to Information Act, 2005 is one move that will be met with consensus across party lines. The need to include political parties under the purview of the RTI was precipitated by a complaint filed by RTI activist Subhash Aggarwal, against the BJP, Congress, CPM, CPI, NCP and the BSP.

The central grievance of Mr. Aggarwal in his complaint pertained to the want of financial transparency, in support of which he has cited exhaustive data relating to concessions, property allotments, tax exemptions granted to the concerned parties, among other things. However, the center suspects that the ruling of the Central Information Commission on June 3, 2013 that expanded the scope of the RTI to these 6 political parties qualifying them as “public authorities” could be a recipe for disaster.

While a citizen’s ‘right to know’ is already a constitutionally protected right under Article 19 of the Constitution, the need to implement the RTI in order to make the political parties more accountable poses a more complex question.

Political parties as public authority

In order to encompass any authority under the ambit of the RTI, it must first satisfy the definition of a public authority under Section 2(h) of the Act. Thus, “public authority” includes “any body made by the government that is owned, controlled or substantially financed” or a “non-governmental organization substantially financed, directly or indirectly by funds provided by the appropriate government.”

Political parties exercise immense control over the cognitive faculties of their electorate and from time to time provide a sense of optimism to give vent to the people’s thoughts. It is because of the direct and indirect power wielded by political parties, by way of which they influence public policy and opinion that they garner the character of a ‘public authority’, the same that was echoed by the Central Information Commission order dated June 3rd, 2013. More importantly, political parties enjoy a constitutional mandate as per the 10th Schedule of the Indian Constitution and have the power to disqualify its members on grounds of defection, or at times when they perform contrary to the party whip. This ability of a political party to shape public opinion and punish members fundamentally opposed to its stance reinforces its ‘public character’.

Perhaps, the most important aspect that lends political parties the color of a public authority is the fact that they receive “substantial” indirect financing from the government.

Section 13 (A) of the Income Tax Act, entitles political parties to full exemption of tax on their incomes. Further, the Information Commission has taken into account that during the last three years, parties such as the BJP received IT-exemption to the tune of 141.25 Crores, the Congress received exemptions up to 300 Crores & the BSP received 39.84 Crores worth of exemption from Income Tax. Even a Cricket Board, enjoying substantial exemption from income tax has been considered to be a public authority. Similarly, the amount spent by the Government on All India Radio providing free airtime to political parties during the 2009 Lok Sabha polls was 28.56 Lakhs.

While interpreting the word ‘substantial’ in the RTI Act, the Delhi High Court in its decision stated that the word ‘substantial’ does not have to be read as ‘majority’. Thus, considering the aforementioned figures and the fact that large plots of land have been allotted to political parties at concessional rates, one can deduce that political parties are public authorities that are in consonance with Section 2 (h) of the RTI Act.

Questioning the need

Having conceded that political parties can be considered ‘public authorities’ for the purpose of the Act, one needs to probe the object of this move. It needs to be understood that not all political parties have the requisite infrastructure, manpower or financial clout to cater to the queries raised by the RTI proposals, primarily because the Indian political horizon is dotted with diverse political parties that have very different operational machineries. Not only could this move be futile, but also counterproductive, since it could take parties away from the prime purpose for which they have been set up- espousing and sharing an ideology, which according to them would bolster or conceive programs for the country, if political rivals use such RTI proposals frivolously.

More importantly, pleas raised by advocates wanting to subject political parties to the RTI Act have shown to highlight questions regarding whether a political party fulfilled its guarantees mentioned in the election manifestos. There have also been some pleas pertaining to deliberations taking place in party meetings. While RTI proposals wanting to access discussions of political meetings may carry with themselves the potential to be misused by rampant and needless requests, it is more important to note that even before the conception of the RTI, political parties had been voted in and voted out solely based on the promises they did or did not fulfill!

Finally, financial accountability of political parties remains an uncompromising need, however, looking at the existing mechanism, the Election Commission already has the power to request the accounts of all the donations received by political parties that are in excess of 20, 000 rupees, every year under Section 29 (C) of the Representation of People Act.

There does also exist judicial precedent that has aided in cleansing Indian politics. In 2002, the Supreme Court issued 5 guidelines to the Election Commission on the voter’s right to know about the candidates that included declaration of assets, liabilities, educational qualifications and a criminal record of the candidate. Thus it can be said that despite the RTI Act, the voters can yet hold political parties accountable.

Holding political parties accountable is an indispensable need since they are the final brokers between the aspirations of an electorate and the will of the government to actualize them. However, it would be fallacious to say that a mechanism working on those lines is absent. Although a political party could be construed as a public authority for those wanting it to do so, the practical harm arising out of it would outweigh the benefit. Let’s not let emotion come in the way of pragmatism.