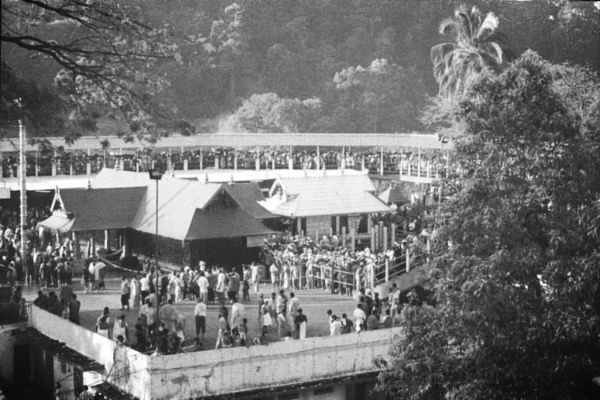

When A ‘Christian Conspiracy’ Was Hatched in 1950 To ‘Destroy’ Sabarimala

In 1950, the Sabarimala temple was found gutted by fire with damages to the Ayyappa idol.

Saying that the act of setting fire was deliberate, a senior police official said it was not possible for any Hindu group to have committed the crime.

Circumstantial evidence pointed at the Christian community.

The stand-off between devotees and the Kerala government in allowing women of reproductive age into the Sabarimala Ayyappa Temple, following a Supreme Court judgement, has led to allegations of conspiracy. Though the Supreme Court has said women of all ages should be allowed into the temple, there has been a widespread demand for a review of the judgement.

The Kerala government, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, however, seems keen to implement the judgement and has ruled out any review. Critics point out that Vijayan has not shown the same keenness to implement other Supreme Court judgements. The apex court on Tuesday (23 October) said it would hear the review petitions on 13 November.

On the other hand, a majority of the devotees, opposed to the entry of women of reproductive age that will affect Ayyappa’s eternal bachelor status, allege that a conspiracy is being hatched to dilute the significance of the holy shrine itself. Their argument is based on the enquiry report filed by K Keshava Menon, Deputy Inspector General of Police, Special Branch, Criminal Investigation Department (on special duty), in the 1950 Sabarimala temple arson case.

The case is about the Sreekovil (main temple), mandapam (hall), and store room being found gutted by fire on 14 June 1950 by a temple employee. Unravelling the mystery behind the fire was challenging because the temple had been closed from 20 May 1950 until its opening on 16 June, and the employee had gone to prepare for the opening. A disturbing bit of information on the fire incident was that Ayyappa’s idol was found damaged.

A police team that went to Sabarimala found 15 violent cut marks on the door leading to the main temple, which, Menon said, indicated forcible entry into the premises. The idol’s head was broken and its left palm and fingers were separated with cut marks on its face and forehead. Menon said the team’s conclusion was that an attempt was made to break the idol and an axe, found at the spot of the incident, was used to cause the damage.

The police official straightaway concluded that the fire caused to the temple was not an accident. They ruled out any robbery attempt since none of the jewels or valuables were taken away. Saying that the act of setting fire was deliberate, and one that was well-conceived and executed, Menon said it was not possible for any Hindu group to have committed the crime.

Pointing out that Christians in the area were more familiar with the region as they were living at the base of the hill, the police official said no Hindu group could have gone up without the Christians noting them. On the other hand, the Christians had no regard for Hindu temples or idols, and circumstantial evidence pointed at the community.

One reason for Menon to see the arson as a Christian conspiracy is that the areas or “necklace” surrounding Sabarimala was treated as a garden (Pungavanom) of Ayyappa by Hindus and, hence, they opposed hunting of wild animals like bisons by Christians in the area. The police official said long before Mahatma Gandhi advocated entry of all castes into temples, Sabarimala had seen Brahmins rubbing shoulders with lower castes. This had acted as a barrier from well-to-do Christians absorbing poorer Hindus into their religion.

The formation of Hindu Mahamandal and controversial remarks by its leaders at a convention could have contributed as a cause or motive for setting the Ayyappa temple afire. Menon said he had investigated the case as an ordinary arson incident and the motive became clear during the course of his probing. The investigating team had a tough time in ascertaining the date of the incident, but after investigations estimated the date as between 26 May and 27 May 1950 (on the seventh and eighth days of the Malayalam month “Edavam”).

Listing out the name of four groups that had moved around the temple’s vicinity during the period when the arson took place, Menon says a group of Christian hunters were in the vicinity of the temple, raising suspicion of the group in setting it on fire. Though those who were probed had made statements before a magistrate that they had not visited the temple, their very presence in the area was suspicious. However, in the absence of any confession, police could not proceed further.

Menon said the case of two persons—Kunhupappan and Paili, a game watcher—falling sick all of a sudden on 29 May and 30 May 1950 were the ones that pointed at a conspiracy. Paili, in particular, had said he had been sick for over a week before that period and had visited the hospital only on 29 May, which was questionable. Paili’s house was nearer to the hospital, and he had told his officer that he had fallen sick at a different place called Rannikovil.

On another occasion, Paili said he was at another place called Mathamba. His officer said Paili did not fall sick and had been marked absent without permission at his workplace. An employee of Mathamba estate, Verghese had requested the officer to excuse Paili’s absence. Menon said the game watcher had deliberately tried to create alibis for his absence and, hence, he prepared a hospital record of his illness.

Wondering what made Paili to not admit that he was part of the hunting party, Menon said something sinister and damaging was committed by him. It made the police suspect that Paili could have been involved in the arson of burning down the Ayyappa Sreekovil, mandapam, and storeroom. As a game watcher, Paili could have prevented any offence in the forest, or, at least, he would have been well-informed of the offences there.

Kunhupappan, falling sick during the same period as Paili, was also strange and suspicious, though he had satisfactorily explained his movements, the police official said. What actually left Menon unconvinced about the Christian hunters’ explanation of their movements was their version that they had set out to the forests to harvest cardamom for a marriage in their owner’s family.

The statement by another person, Ouseph, that he went back to his owner to report that there was no cardamom plant and, hence, he couldn’t get any was a trumped-up story, the police official said, adding that it was an attempt to cover up his movements or knowledge of the incident at the Ayyappa temple.

The point is, the police official is questioning why a team was sent to harvest cardamom incurring huge costs when there were no plants there. The owner, who had allegedly sent the team to harvest cardamom, could have got the spice easier and cheaper as his brother owned a cardamom plantation.

This meant that Ouseph and a few of his friends had moved about in the forest not for harvesting cardamom but for some other purpose. Menon says the irresistible conclusion is that it was an attempt to camouflage his complicity in the offence. Otherwise, he would have to confess his presence near the temple and explain his activities. The statement of Ouseph and his co-hunters all seem to be a cock-and-bull story made up on instructions of some party, who they were trying to protect.

The police official also finds another statement by these hunters weird. Kunhupappan said before setting out for hunting, they had bought Rs 50 worth provisions on credit, but Ouseph said they had paid cash. Menon says the shop from where the provisions were bought doesn’t have goods totally worth over Rs 20 and the shopkeeper had denied selling any provisions to the team!

Menon draws attention to a curious incident in January that year that could indicate an organised plan to destroy Sabarimala. Ouseph said he had gone with a group of six Christian plantations owners that had set out from Erumeli in a jeep to a place called Kalaketti, from where the team went on foot to Kollamuzhi and halted there. After asking their employees to go into the forest for hunting, Ouseph and the six owners had gone to Nilakkal in search of a church that was believed to be existing there.

Saying that such a search was surprising, the police official said they were either trying to set up a church there or prove the existence of one at that place. The desire for a church around Sabarimala was deep-rooted among the owners, and there was no other purpose for them to go to Nilakkal.

The Christians were disturbed by the poor and lower-caste Hindus visiting Sabarimala with devotion and fervour, and wanted to check it. Otherwise, the growing trend of converting lower-caste Hindus would be checked, the police official concluded, adding that, in the long run, it would have helped the Christians colonise the area and exploit the fertile region.

Menon said a Game Association Ranger had reported the movements of K T Abraham, a member of one of the plantation families, in March, April, and May in the Sabarimala area. The police official said when seen in the background of various events, including the fire incident and Nilakkal visit, the movements were something to do against the existence of the Sabarimala temple.

Menon concluded that based on the statements of the suspected persons, there was no doubt that the crime was “a fanatical one and perpetuated with a view to satiate fanaticism”. The police could have arrested the suspect, but the team could not conceive the next step due to various difficulties and, hence, it shelved such a move. Rains soon after the crime was committed compounded the problems for the investigation team and, thus, the team could only point at the suspicions against persons like Kunhupappan and Ouseph.

Interesting, the Ayyappa idol that replaced the damaged one was made by P T Rajan, father of P T R Palanivel Rajan, who was a minister in the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, which is sworn to atheism, and grandfather of the party’s Madurai Central Assembly member, P Thiagarajan. Unfortunately, despite Rajan publishing documents on this, the Travancore Board of Devaswom (TBD) doesn’t mention this on its website. Thiagarajan’s letter to Kerala Chief Minister Vijayan and TBD in this regard has met with no response.