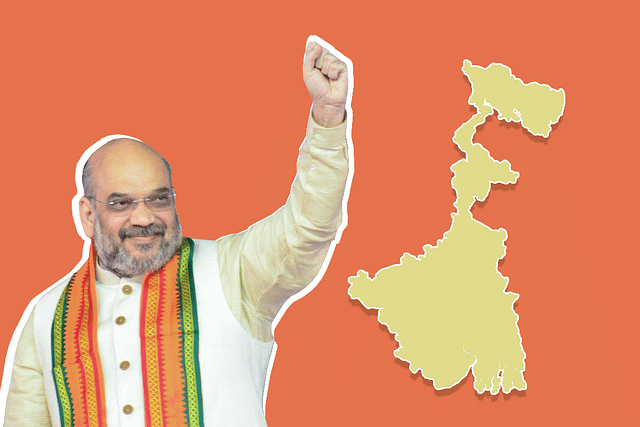

Why A BJP Victory In Bengal Could Change The Course Of Dalit Politics In India

The BJP’s and the larger Sangh Parivar’s openness to viewing Dalits and tribals through the prism of the larger Indic ecosystem places them in a position of advantage while reaching out to these groups.

The party’s success in the state could signal the next stage in the evolution of Hindutva politics in India.

A storm is brewing in West Bengal.

While there may be questions abound on the personal fate of the state’s current Chief Minister Mamta Banerjee in her ill-advised battle in Nandigram, almost all credible political indicators point towards the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) forming the government in the eastern state.

If these trends materialise, it would be the culmination of an incredible journey for the saffron party in Bengal. Just five years ago, the BJP’s vote share in the state was 10.16 per cent and it won only three seats. To put things in perspective, Banerjee’s Trinamool — whom people expect it to displace in 2021 — won 211 seats with a vote share that was more than four times that of the BJP.

It is not just the enormity of the electoral turnaround that is interesting — it is also the symbolism that goes with it. Bengal had been a Left citadel for 34 years and a ‘secular’ one for a decade longer.

Much of the intellectual class, which is inimical to the BJP as a matter of principle, have built it up over the years as an idyllic state, whose inhabitants were blessed by birth with an innate understanding of the Nehruvian ‘Idea of India’ — just the kind of place where the supposed crass tentacles of Hindutva would never get a hold.

These qualities of the state had also allowed its rulers — both the Left and Trinamool — to get a sort of blank cheque from the media and the Delhi elite. The state’s horrible developmental indices, non-existent law and order along with its rampant corruption were swept under the rug — in the larger interest of India’s ‘secular’ ideals.

For the BJP, a victory in Bengal would only be comparable (in scale and importance) to its sweep of Uttar Pradesh in the assembly polls of 2017. The state sends 42 MPs to the Lok Sabha — third only to UP and Maharashtra — making it a key conquest for the party in 2024.

Furthermore, the political capital invested by both the Prime Minister and the Home Minister in the state — in spite of the pandemic — makes it a must-win. The raising of the saffron flag in a state which was considered impossible for the party would send a big message to other hitherto untouched territories.

No doubt, the likely results in Bengal will be accompanied by the characteristic cries of the ‘murder of democracy’, ‘campaigning during the pandemic’ slogans which are being warmed up by the usual suspects as we speak.

However, what the political analysts at Lutyens are likely to gloss over is the marked difference which will characterise any BJP victory in Bengal over its previous successes. If they did manage to delve deep, the findings are likely to shock them more than ever before.

While the initial rumblings were seen during the 2018 local body polls, the BJP’s rise to become the primary political opponent to the Trinamool in the state was actually first evidenced in its unprecedented performance in the 2019 national elections, when it zoomed to a 40 per cent vote share in the state and won 18 seats — just four behind the Trinamool which was expected to sweep the state.

The scale of the party’s rise in the state was stunning. Out of the state’s 42 Lok Sabha seats, it had an increase of vote share in every constituency of the state — 19 of the seats saw a jump of over 25 per cent. The party’s increase in support managed to even engulf an increase in vote share for the frontrunner Trinamool in many constituencies. These are results that would make any political leader swoon.

However, what is more interesting is the areas and voter groups where the BJP made these gains. Unlike the conventional political wisdom surrounding the party being an urban and upper caste phenomenon, especially when it seeks to grow in new territories, the Bengal experience turns such notions on its head.

In 2019, the BJP swept both Northern Bengal and the western, tribal-dominated regions of Jungle Mahal — both regions which are primarily rural — while the Trinamool managed to hold on to its dominance of the urban Kolkata regions.

The key groups which moved towards the saffron party in large numbers were not from the upper or middle castes either — rather it was from the Schedule Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes.

The party’s increased popularity among SC communities like the Koch Rajbanshis and Namasudras was the base upon which its growth in Bengal was built.

The Rajbanshis are primarily concentrated in the north of Bengal while the Namasudras are a numerically powerful SC community present across the state. Both communities have voted for other parties in the past — the Matua sect of the Namasudras, with their anti-Brahmin history behind them, used to be Left voters traditionally before a section began to move to the Trinamool in 2011.

Neither of these communities are the ones that most political watchers would select as first movers towards the BJP but a glance at Banerjee’s politics in Bengal post 2011 and an understanding of the legacies of both communities provide fairly easy explanations for this shift.

The Rajbanshis are primarily found in the north of Bengal — the region most hit by illegal immigration from Bangladesh — and have found themselves at the receiving end of Banerjee’s heavy minority appeasement and the rapid demographic changes seen in the region.

The stark communal polarisation can be evidenced from the fact that while the BJP swept this region, the TMC also managed to increase its vote share in the northern constituencies in 2019.

The Namasudras, on the other hand, form a bulk of the immigrants who came back to India from Bangladesh. The remnants of their experiences in Bangladesh, the minority politics of the TMC and the promise of citizenship from the BJP have moved this community decisively towards the saffron front.

The movement of tribal votes for the BJP in the Jungle Mahal region follows a similar pattern as well — of historically disadvantaged communities migrating to the Hindutva politics of the BJP in the face of the goondaism and blatant appeasement politics of the Trinamool.

While the importance of immediate motivations for such shifts cannot be ignored, there also exists the cultural legacy that these groups hold which makes them primed for Hindutva. For example, the Matua sect of the Namasudras have a history of staunch Vaishnavism — no doubt a catalyst in them choosing to align with a Hindu-leaning front the moment it became a credible political option.

If these trends hold, West Bengal could signal a change in how Hindutva politics and also, Dalit politics are conducted across the country going forward.

For long, anti-Hindutva political alignments have worked on the assumption that Dalits and tribals have, by default, an inimical relationship with Hindu iconography. Hence, the aggressive targeting of Dalits, the promulgation of anti-Hindu narratives and attempts at artificial coupling of Dalits with minority groups have been the staple strategies of any anti-BJP political formation across the country.

Most of these political formations are Leftist or have a socialist background. The legacy of the Left worldview encourages these parties to look at Dalits through the prism of class warfare and then, as realities of India’s caste structure arise, superimpose generic caste interpretations onto Dalit groups as a whole.

What Bengal shows is that such interpretations are incorrect and that Dalits across the nation do not exist as a unified group with homogenic experiences and motivations. Even more importantly, it also shows that in the face of demographic changes and cultural attacks, Dalit groups can move towards the larger Hindu tent and become key players in a rainbow Hindu alliance.

In such a situation, the BJP’s and the larger Sangh Parivar’s, understanding and openness to viewing Dalits and tribals through the prism of the larger Indic ecosystem places them in a position of advantage while reaching out to these groups.

And, more importantly in the larger scheme of things, it signifies that the crude anti-India and anti-Hindu narratives being pushed across Dalit and tribal communities across the country by ‘breaking India’ forces will not reap the dividends that its owners imagine.

Whether this will push the ‘secular’ parties to adjust their strategies or not is a question that remains to be answered but what is certain is that limits of the current approach are close to getting reached.

Politics, of course, is never uni-dimensional. The BJP’s long-term fate will depend on several factors other than its performance in Bengal — including the response to the ongoing pandemic.

However, if the post-pandemic political environment turns out to be favourable, the party’s success in the state could signal the next stage in the evolution of Hindutva politics in India.

Praful Shankar is a political enthusiast and tweets at @shankarpraful