Why Babus Remain Above Public Scrutiny: Will A TV Satire Do The Trick?

Reforms bandied about by the political class often do not see the light of day thanks to red-tape.

Minister Jim Hacker: What for? What is the ultimate purpose of government, if it isn’t for doing good?

Sir Humphrey Appleby: Minister, government isn’t about good and evil, it is only about order or chaos. (Yes, Minister: Third Season, Episode 6: The Whiskey Priest)

One might argue that all systems of governance eventually tend to a bureaucracy as it offers order and governance based on written rules and documents. In addition to this, the members of the bureaucracy are selected through a competitive and fair examination/recruitment process, and they are ranked in a hierarchical manner based on seniority once they enter the league. Further, each bureaucrat functions in his own fixed domain assigned to him/her. The sociologist, Max Weber, theorised the above features in his study of bureaucracies.

Bureaucratic intrigue, corruption and red tape are colonial vestiges adopted ably by our establishment in post-Independence India. The case may not be very different even in developed nations either. Some glimpses of this phenomenon have been captured well in the British TV series Yes, Minister and its sequel, Yes, Prime Minister.

Yes, Minister and its sequel Yes, Prime Minister are British satirical TV shows on the bureaucracy. The role of Jim Hacker, the minister of department of administrative affairs, is central to the TV series. Permanent secretary Humphrey Appleby and his junior in the ministry, Bernard Woolley, are close aides of the minister. The conversations and dealings between the three form the central storyline of the series. The role of chief secretary Sir Arnold Robinson articulates the position of the bureaucracy and guides Appleby through difficult times. The TV show covers a wide range of administrative issues that a government faces in its day-to-day functioning.

Most bureaucracies prefer status quo to any change, mainly to hedge against risks and personal liability for the consequences of their decisions. The desire for status quo of the sarkari babu (a term used for an Indian bureaucrat) is even stronger in a country as diverse and chaotic as India. One cannot deny the fact that the ‘steel frame’ of the civil services, as described by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, has contributed to the progress of India in the past seven decades. But the irreparable damage done by them through complicated regulations, corruption and their unholy nexus with politicians might never be quantified in real terms (no offence to the Iron Man of India).

Invention Of Hypothetical Barriers To Delay/Stall Work

Jim Hacker: When you give your evidence to the Think Tank, are you going to support my view that the Civil Service is over manned and feather-bedded, or not? Yes or no? Straight answer.

Sir Humphrey: Well, Minister, if you ask me for a straight answer, then I shall say that, as far as we can see, looking at it by and large, taking one thing with another in terms of the average of departments, then in the final analysis, it is probably true to say that at the end of the day, in general terms, you would probably find that, not to put too fine a point on it, there probably wasn't very much in it one way or the other, as far as one can see, at this stage (First Season, Episode Five: The Writing on the Wall).

On other occasions, when there are no risks in a decision/task, the babu twists the interpretations of the rule to make it impossible for the normal citizen or politician to get his work done. This move is often a ploy to obtain some sort of benefit for oneself before doing the work that the babu is obliged to do without such inducements. The refusal of the bureaucrat to get your work done with the excuse of ‘lack of time’ or ‘constraints imposed by rules’ itself is an indication to the other person that the work shall not be done without the customary inducement.

This claim deserves to be justified with a personal experience. I had my first straight encounter with a babu on my eighteenth birthday at the Regional Transport Office to get my learner's licence. The person promptly told me that learner's licence cannot be given until the next day as I cannot be considered an 18-year-old on my birthday. “You won't turn 18 till this day passes,” is what he told me. Thereafter, I realised that one can ensure that all perceived ‘barriers’ for a task would magically disappear when crisp notes were produced to the officer in question.

House-Trained Mantris

Sir Humphrey Appleby: We’ll have him house-trained in no time. (First Season, Episode One: Open Government)

Not many would disagree to the fact the every minister who gets into office is often ‘house trained’ by the bureaucracy so that he/she dances to the tune set by them. One can imagine the grip of the babus on Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has made them say on the floor of the house that Article 370 will not be repealed. The same clique would have influenced the likes of Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj to bend rules and cover up her mistake in the Tanvi/Sadia passport fiasco in order to save her ‘secular’ credentials. If the situation is so blatantly visible at the top echelons of central government, one can only wonder the effect of bureaucracy at the state level, where many ministers are often unaware of the complicated maze of laws, rules and twisted language deployed in government files. Sometimes, politicians and political parties are forced to water down their core ideologies because of the house training they receive from the bureaucracy. A classic example of this was the answer given in Parliament by the Minister of State for Home Affairs Hansraj Ahir. The answer provided by him, on 27 March 2018, is reproduced below:

Question: (a) whether the government is committed to scrapping Article 370 of the Constitution which gives special status to the State of Jammu and Kashmir; and (b) if so, the details including the present status thereof along with the procedure laid down for such scrapping?

Answer: (a): There is currently no such proposal under consideration of the government (b): Does not arise in view of (a) above.

Let us remind ourselves that the answer was given by a party, which has had the matter of Article 370 on its manifesto for Lok Sabha elections. There is no hint of scrapping the provision in future as well. The minister, no doubt, has read out the answer written by a babu obediently.

Policies Watered Down In Bureaucratic Language

Sir Humphrey: We'll have him house-trained in no time. He swallowed the whole diary in one gulp and I gather he did his boxes like a lamb last Saturday and Sunday. As long as we can head him off this open government nonsense.

Bernard: We are calling the white paper as ‘Open Government’.

Sir Humphrey: We dispose of the difficult bit in the title. It does less harm there than in the text.

Sir Arnold: It's the law of inverse relevance. The less you intend to do about something, the more you keep talking about it. (First Season, Episode One: Open Government)

The smart city idea of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is a classic example of ‘disposing the difficult bit in the title’ by the bureaucracy. If one opens the smart city mission site and goes to the section “What is a Smart City”, we find Humphrey-esque language:

<i>The first question is what is meant by a ‘smart city’. The answer is, there is no universally-accepted definition of a smart city. It means different things to different people. The conceptualisation of smart city, therefore, varies from city to city and country to country, depending on the level of development, willingness to change and reform, resources and aspirations of the city residents. A smart city would have a different connotation in India than, say, Europe. Even in India, there is no one way of defining a smart city.</i>

Considering the scarce financial resources of the government, we have reason to believe that Indian cities can't be transformed into premier metropolises like Singapore or London in a short term or even a long-term outlook. Every year, we see Mumbai's flooded streets in monsoon and the Bengaluru's roads are clogged with traffic. But one must note how smartly the bureaucracy has killed the project which gave many the impression that our cities would actually transform into ‘smart cities’.

The Work Of Bureaucracy Is Kept Under Wraps By Default

Bernard: But surely, the citizens of a democracy have a right to know.

Sir Humphrey Appleby: No. They have a right to be ignorant. Knowledge only means complicity in guilt; ignorance has a certain dignity. (First Season, Episode One: Open Government)

In spite of the Right To Information Act and its provisions, much of the work of the government is often not revealed. The public barely knows the inner workings of the government and effectiveness of government programmes. This short exchange between a junior bureaucrat, Bernard, and his senior, Humphrey, Appleby in Yes Minister's first episode mirrors the opinion of the typical babu regarding right to information.

At the same time, one truly wonders why a satire on the Indian bureaucracy has never been attempted by Indian television producers. Though there was an Indian adaptation of the series in India (Ji Mantri Ji, 2000), one would have hoped for an Indian series which captures the scenario in India.

Is Bureaucracy A White Elephant?

Humphrey Appleby: Bernard, you know perfectly well, that there has to be some way to measure success in the civil service. The British Leyland measure their success by the size of their profits, or to be more accurate, they measure their failure by the size of their losses. But we don't have profits and losses. We have to measure our success by the size of our staff and our budget. By definition, Bernard, a bigger department is more successful than a small one. (Season 1: Episode Three: The Economy Drive)

The bloated size of the civil service has been a matter of debate in India. The perks, benefits and prestige accorded to the service is a matter of envy. But the question remain as to whether the size of the bureaucracy justifies the workload of the specific departments. The PM's slogan ‘minimum government, maximum governance’ definitely calls for a trimmed down bureaucracy. Whether a step has been taken in the direction or not is a question that remains unanswered.

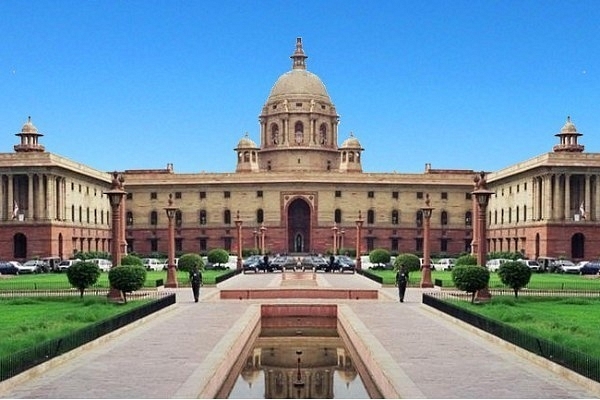

In spite of these striking similarities, the Indian scenario is complicated by entrenched ‘Lutyens class’ and a culture of nepotism. The situation is complicated even more by caste and religious diversity in India. In states such as Karnataka, pontiffs of religious mutts don't hesitate to speak out on transfer of officials belonging to their community. Though articles and op-eds are often written on the need for reforming and sizing down the bureaucracy, citizens are often apathetic regarding this issue. A satire on the bureaucracy would serve as a mirror to the permanent rulers of India. It would make people aware of the amount of power this class wields in the establishment. Unless the conduct of the bureaucracy becomes a matter of discussion on TV screens through a satire or otherwise, people will be under the impression that politicians are solely responsible for their plight. Meanwhile, the sarkari babu will continue to remain immune from public scrutiny and criticism.