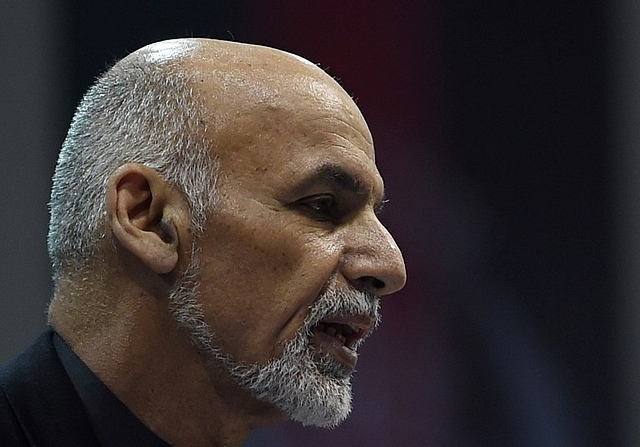

Ghani's Visit: Damage Control Opportunity For India

The Afghan President hasn’t been as warm towards India as his predecessor was. He has visited and made deals with China, the US and even Pakistan before scheduling a visit to New Delhi. Will this visit improve Indo-Afghan ties?

In a few hours, Afghan president Mohammad Ashraf Ghani will be landing in Delhi. This will be his first visit to India after he took over his new job in September 2014. Ghani’s visit is in response to an invitation extended to him by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the summit of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation in Kathmandu in November, 2014. This visit is important to both nations: for Modi, it is an opportunity to ensure that Afghanistan has not slipped out of India’s grasp, and if it has, to woo it back; for Ghani, it is to persuade a powerful neighbor and longstanding ally that, Afghanistan would never let a security threat emerge on its soil against India.

Afghanistan’s history with South Asia is long. Upon partition of the subcontinent, Kabul initially refused to recognize Pakistan. An old dispute over the Durand Line only added to the animosity between the two states. While it is difficult to call Afghanistan an Indian ally during the Cold War, it was certainly more sympathetic towards India than its younger Islamic cousin. Indians also remembered fondly the role of the Pashtuns, under Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, in the Freedom Movement and supported an independent country for the Pashtuns in the North West Frontier Province.

The rise of the Taliban in the early 1990s after the Soviet retreat from Afghanistan saw India’s star on the wane in Kabul. India’s fortunes shifted in 2001, when the United States invaded the mountainous Central Asian country and removed the Taliban from power. However, it was a brave new world, and non-state actors motivated by their faith and a desire to impose it upon the world did not give the Western coalition a clean victory. Though Indians are loathe to admit it, Afghanistan has been the site of a proxy war between India and Pakistani-backed terrorist organizations ever since.

The elections of 2014 also marked a slight tremor in Afghanistan’s foreign relations. Hamid Karzai, who had been the first post-Taliban president of Afghanistan, and his men who were cut from the old cloth, had studied in India or developed close personal connections with Indian officials during their war against the Taliban. Raised in their own country, they had a certain sense of its history and place in the world which usually tilted heavily towards India. Ghani’s ascendancy put an end to India’s soft power among Kabul’s lawmakers. Born in Afghanistan but educated in Lebanon and the United States, Ghani’s career was spent almost entirely in the West at universities and then the World Bank. Ghani’s topic of interest was his country and its neighbourhood. He returned home in 2002, serving his country most ably as its finance minister for two years until he became the chancellor of Kabul University. Unlike many Afghan leaders, including his CEO Abdullah Abdullah, Ghani has not exhibited any sentimental attachment to India; in fact, his reputation as a technocrat preceded him and he went about matters of state in a rational manner without the encumbrances of history.

Delhi has been watching with mounting concern the actions of the new Afghan president. Ghani’s first foreign visit, if such things are indicators of predilections, was to China in October 2014. This was followed by a trip to Pakistan in November of the same year, the United Arab Emirates in January 2015, Saudi Arabia in mid-March, and the United States soon after that. It is of note that the Afghan president is yet to visit India, Russia, or Iran (though Abdullah has been to Russia and India just before the trip to the United States). Kabul’s broad strategy seems to prioritise the end of terrorism in its realm. To do this, Islamabad must be engaged and hopefully assuaged that Afghanistan will not be an Indian knife in Pakistan’s back. Ghani’s pragmatism is on display when his first port of call in Pakistan was the Army General Headquarters in Rawalpindi rather than Islamabad, the seat of the Islamic Republic’s government.

To ensure that “the boys in Rawalpindi” deliver on their promises to his country, Ghani has reached out to China, who, he hopes, will have more influence over Pakistan. An additional reason to approach China is to entice it with lucrative economic opportunities. Beijing has shown in Central and Southeast Asia that it can invest enormous capital in projects of interest – energy and infrastructure. Ghani hopes that his developmental goals coincide with Beijing’s ambitions to restart the Silk Road wherein Afghanistan can emerge as the hub for transportation, energy, and telecommunications, connecting East and Central Asia to West Asia. China’s increased financial stake in the stability of Afghanistan would ensure its support against Pakistani-sponsored terrorism. This bet seems to have paid off with China offering – for the first time – to mediate a solution in another country’s internal affairs. Ghani has also courted Saudi Arabia and the UAE in the Gulf who are sources of financial assistance and possess the capability to exert financial pressure on Islamabad, if necessary.

This vision is most clear in Ghani’s address to a joint session of the US Congress. He spoke of women’s education and rights, security, corruption, and development. Ghani reiterated that he sees the United States as a partner in the fight against terrorism, and that the new Afghanistan can have no place for radicalism or intolerance but encourage rationalism and scientific enquiry. He stressed reconciliation and justice, but at the same time reminded everyone that the Afghan knew how to fight if necessary.

Ghani embraced globalisation and promised to develop institutions that will take the country forward in an inclusive manner, using the wealth of natural resources for the benefit of all. In essence, the president laid out his dream for an economic miracle in Afghanistan, a dream that could come true only through security and stability. To emphasize to his hosts that he meant business, Ghani took Abdullah along with him to demonstrate that their alliance, mid-wifed by the United States, was still strong. This has played well, with US newspapers proclaiming that Ghani is the sort of leader that Washington needs in Kabul. In response to a direct request, US President Barack Obama has slowed down the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan to give the Afghan National Army more time to arm and train its soldiers.

If India feels left out of the party, it is because the new leadership in Kabul sees it as an unreliable partner. India was hesitant to deploy troops in Afghanistan even to better protect its own assets; when Kabul came knocking repeatedly for arms, Delhi would offer all support short of help. India even failed to arrange supplies and spares for the ANA. Relations between the two states have cooled somewhat over the past six months, notwithstanding separate visits by India’s foreign minister, national security advisor, and the foreign secretary to Kabul. Admittedly, India has invested two billion dollars in Afghanistan and extended assistance in several sectors such as education, health, and telecommunications but that is a drop in the bucket compared to what Kabul needs and others such as Beijing and Riyadh can offer.

One sign of this coolness is that Ghani has suspended the construction of a $400 million tank and aircraft refurbishing plant funded by India while increasing the number of Afghan officers trained by Pakistan; it is rumoured that a request for heavy arms from India has been similarly suspended. While Islamabad is yet to take steps to combat terrorism emanating from its soil into Afghanistan, the Chinese have already facilitated a meeting between the Taliban and Kabul during Ghani’s visit to Beijing. It is anyone’s guess as to how much pressure was put on Pakistan to arrange the meeting.

Ghani’s visit now will be to convince Raisina Hill that his actions do not threaten Indian interests. However, Delhi cannot countenance the increased influence of its two rivals over Kabul. Whether Ghani can be won over or not, it would go a long way in strengthening the hand of the Indian lobby in Ghani’s government, were India to now take a stronger interest in its neighbour.

So far, Modi has demonstrated a vision and acumen with the countries of the Indian Ocean Region that has never been seen before. The question is if he can do the same with Afghanistan and reverse that country’s slide away from India. One thing that may help Modi is Ghani himself: so far, the Afghan leader’s developmental plans have been all about the long term and have had little to show for themselves in the present. There has been dissatisfaction among Afghans with Ghani’s olive branch to Rawalpindi; powerful voices among Afghanistan’s tribes may lend their weight to the unhappy rumblings and weaken Ghani’s alliance. The ANA has no goodwill for Pakistan either, believing the latter to be in cahoots with Afghanistan’s non-state enemies. With poverty and unemployment rampant, an economic crisis or an insurgency can be devastating for Ghani, as well as for Afghanistan. If Modi can promise – and deliver on – a more proactive Indian role in Afghanistan vis-a-vis security and infrastructure, it will bring some balance in Ghani’s strategy.

It would be myopic of Islamabad to squeeze the maximum concessions out of Ghani and then abandon him. For one, the concessions may be easily reversed by Ghani’s successor. Secondly, Ghani is the most pro-Pakistan Afghan leader since the Taliban and it would be foolish for Islamabad to undermine his power. However, if Rawalpindi does take steps against terrorism as they promised Ghani, it will also be to India’s benefit. Thus, not all is lost for Delhi.

Rather than leave India’s fate in the hands of others, the commonsensical thing for Modi to do is deepen the Indo-Afghan relations via more sensitive areas of defence and intelligence cooperation and soon. It is argued that such measures will only instigate Pakistan but India’s hesitation thus far has hardly borne any fruit either.

Immediate Indian assistance in infrastructural projects and security will be an important demonstration of the increasingly responsible role Modi wants India to play at the regional level. What better place to take that first step than a long-time friend and ally? In the long term, Ghani’s plans for his country serve India’s interests as well; in the meantime, increased influence in Kabul will be a pleasant sweetener for Delhi.