How India Can Unilaterally Walk Away From The Indus Waters Treaty

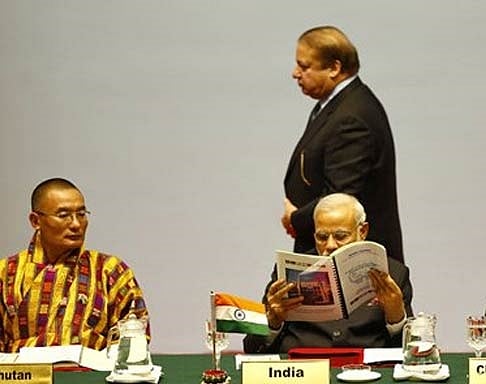

As India reviews the Indus Waters Treaty, Nawaz Sharif says no one country can walk away from the Treaty.

But as it turns out, India can separate itself from the Treaty on its own – and within the norms of international law.

Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has gone on record saying that no one country can unilaterally separate itself from the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960 (the Treaty).

This comes at a time when Pakistan has approached the World Bank, seeking to invoke the arbitration clause in Article IX of the Treaty to prevent India from exercising its rights to the maximum extent permissible under it.

On paper, Sharif may have a case. Article XII (4) of the Treaty reads:

The Provisions of this Treaty, or the provisions of the Treaty as modified under the provisions of Paragraph (3), shall continue in force until terminated by a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the two governments.

A plain reading of this provision would say that unless India and Pakistan mutually agree, the Treaty cannot be terminated. But international law does leave India with some options that it can exercise should it wish to terminate the Treaty unilaterally. With these options, India can terminate the arbitration clause as well and deny the Pakistani request for arbitration.

The law relating to treaties is largely governed by customary international law. This was codified by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969. India participated in the Vienna Conferences, which were held to discuss the draft text proposed by the International Law Commission. In fact, if one goes through the minutes of the sessions, one will find that India's contributions to the draft text have been quite substantial. (For instance, the minutes of Session 1 and Session 2)

However, India has neither signed nor ratified the law on treaties. So, it can make an argument that it is not bound by the additions in the text that were not a part of customary international law at the time of adoption. Put simply, India is party to the contract, but the Contract Act doesn't apply to it; only the general law of contract will.

So, then, how does India get around Article XII(4)?

India can cite the fact that the circumstances under which the Treaty was agreed upon have undergone a dramatic shift in the intervening years and those circumstances formed an essential basis for the consent that was given at the time. India cannot make use of hostilities with Pakistan to make this a straightforward argument, as it has not done so in the past. There have been hostilities in the past, in 1947, 1965, 1971 and, more recently, in Kargil in 1999, but the present circumstances are fundamentally different. Here is why:

Pakistan's duality in power

The Preamble to the Treaty speaks of the Government of India entering into the Treaty in a spirit of "goodwill and friendship" and states that the purpose of the Treaty is to make a settlement in a "cooperative" spirit of any such questions that may arise in the future on the use of such waters. India can cite the fact that it no longer knows who is the lawful civil power in Pakistan with which it is to conclude any agreement or arrangement, given the nexus between the military and civilian state apparatus.

At the time of entering into the agreement, Pakistan was under a military arrangement and has seen the restoration of a civilian government and further coups ever since. However, the current situation is a quasi one, where promises made by the Pakistani civilian government can no longer be held reliable on account of the military and security establishment running a parallel establishment since the apparent restoration of a civilian government after Musharraf.

In the past, India has either dealt with a Pakistani general or a Pakistani civilian leader. Today, India is in a situation where it is difficult to engage in negotiations with either, making goodwill, friendship and cooperation difficult, thereby fundamentally changing the circumstances.

The threat of terrorism

Previous engagements with Pakistan have been on a military level, with civilians largely left out of the picture. But Pakistani sponsorship of terrorism has changed the dimensions, as the Pakistani establishment has begun targeting civilian targets. With the Security Council's resolutions calling on states globally to take steps against nations who are known supporters of terrorism, India has a case to make that the Pakistan of 1960 is very different from the Pakistan of 2016 and, therefore, the circumstances under which India gave its consent to the Treaty in 1960 have been fundamentally altered.

Further, India's commitment to the global war on terrorism also requires it to cease all cooperation with state actors who support and sponsor designated terror outfits. India can cite Pakistan's support for groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jamaat-ud-Dawa (which Pakistan still hasn't banned) as a cause for ending all cooperation with Pakistan.

Indus Treaty was too liberal to Pakistan

India can also point out that the Treaty is one of the most liberal water sharing arrangements in the world, giving 80 per cent of the water to a lower riparian state and call for a realignment of the Treaty with existing norms of international law.

While Sharif may be right on a plain reading of Article XII (4), should India choose to, it can make the argument that this Article, along with the whole Treaty itself, does not bind India and unilaterally terminate it. This would also terminate the arbitration clause.

However, the government may also just exercise its full rights under the Treaty, as it currently plans to do, and make its case before the arbitral tribunal. The dams required to exercise these rights will take many years to construct, so Pakistan has a very weak case for interim relief as there is no impending construction. So if Pakistan is hoping to win any international brownie points by going before the arbitral tribunal, it needs to perhaps rethink its entire strategy..