ICJ Verdict On Jadhav Is A Half-Victory: It Buys India Time To Negotiate A Backdoor Release

What India has truly gained in the ICJ judgement is time and space to negotiate a backdoor release for Jadhav.

The long-term war with ‘Terroristan’ remains a major challenge for India, ICJ or no ICJ.

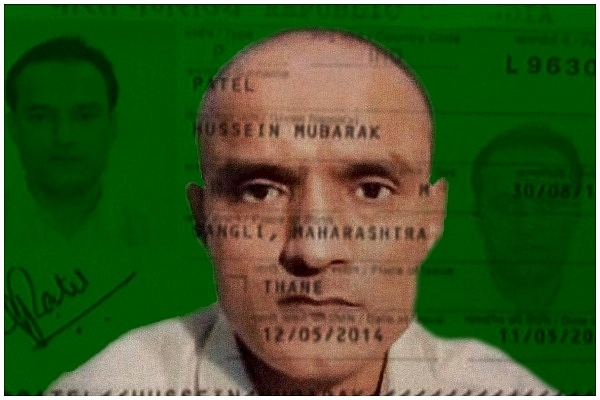

India has good reason to be happy with the 15-1 judgement of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) which held Pakistan guilty of not following the Vienna Convention in regard to Kulbhushan Jadhav, who was awarded a death sentence by a Pakistani military court in 2017.

The verdict, which had only the Pakistani judge dissenting, ensures that Jadhav will not be executed in the near future. It also grants India consular access to him, which raises the possibility of a proper legal defence being mounted on his behalf.

Among other things, Pakistan has accused Jadhav of being an Indian spy who also aided terrorism in that country.

However, the fact that the court did not order his release means that we need to keep our victory celebrations muted. There is much work to do, including preparing his defence, and mounting backroom pressures for his release at some point in time.

Pakistan is a rogue state, and it is not going to give up a bargaining chip like Jadhav so easily. If it really wanted to deal with a spy or alleged terrorist, it could have denied his existence and quietly executed him. That Pakistan made such a show of his capture in 2016, conducted a sham trial and awarded the death sentence suggest that it would like to blackmail India using him as hostage. Jadhav, a former naval officer who retired from service in 2001 and started his own business, is more useful to Pakistan as a propaganda prop than as someone executed without proper legal support. He can also be used as a lever to get India back to talks, something Prime Minister Imran Khan is desperate to revive in order to send the world the message that things are on track.

Pakistan is under global pressure not only on Jadhav, but also terror funding, where it is on the grey list of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). It has avoided joining the black-list only by the skin of its teeth, and even China – which abstained at the last meeting of the FATF – does not seem too eager to support its terrorist friend. In May, China has agreed to put Maulana Masood Azhar of the Jaish-e-Mohammed on UN list of banned terrorists, sending a quiet message to its friend that it also cannot help it endlessly. China probably negotiated a deal on Azhar by getting the US to designate the Baloch Liberation Army as a terrorist outfit, something it could offer Pakistan as a consolation prize in lieu of the Azhar ban.

India’s real leverage in dealing with Pakistan probably comes from two factors: one is the parlous state of the Pakistani economy, which prevents its military from entering into any major misadventure in India, at least in the near term. Secondly, there is China’s new need to avoid provoking India when it is embroiled in a serious trade war with the US, and when the Indian market is so vital to it. This may partially explain why China has gone along with the ICJ judgement on Jadhav and also the Azhar ban.

But China has not abandoned Pakistan, nor has Pakistan abandoned its backing for jihadis in Kashmir Valley. What we have now is a breather while both of them recalibrate their strategies to deal with the more pressing issues they face in today’s global environment.

What India has truly gained in the ICJ judgement is time and space to negotiate a backdoor release for Jadhav. The judgement has put Pakistan on the backfoot and reduced its ability to use Jadhav to bludgeon India into conceding what it wants – talks without preconditions on Kashmir. But Prime Minister Narendra Modi has seen through this game, and is no longer willing to play ball with a party that is unwilling to play by the rules. With National Security Adviser Ajit Doval by his side, the ICJ victory can best be used for a behind-the-scenes deal to free Jadhav, possibly in exchange for some low-level assets held by the Indian side.

The long-term war with ‘Terroristan’ remains a major challenge for India, ICJ or no ICJ.