Merits Of A ‘Forward Policy’ With China

Modi’s ‘bottoms-up approach’ to Beijing may well succeed in tackling a tough neighbor.

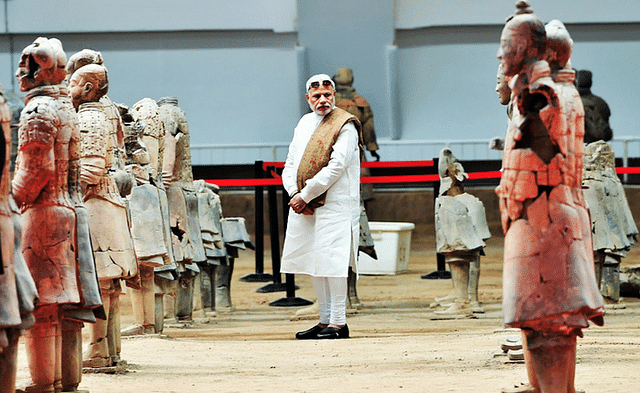

In his first 12 months in office, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has travelled to as many as 19 nations, but none were harder than the just-concluded trip to China. New Delhi’s time-tested policy of appeasement to all has constantly been stretched to its limits by a belligerent Beijing.

Last year, President Xi Jinping’s maiden visit to India was hijacked by repeated incursions by the Chinese army into India’s North East, with sections of the Chinese state-run media deriding New Delhi. And only days before he was to land in China this year, Modi was lampooned yet again by the Chinese state media. Accusing the Prime Minister of “playing tricks” over the border dispute, an opinion piece in the Global Timessaid, “Due to the Indian elites’ blind arrogance and confidence in their democracy, and the inferiority of its ordinary people, very few Indians are able to treat Sino-Indian relations accurately, objectively and rationally.”

India and China have tried to revive their sweet-and-sour relationship numerous times in the past, and each time, they have gotten off on the wrong foot. Differences over the international border, the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean have plagued any positive attempts by either side. Often, the Chinese army and state media have demonstrated a mind of their own – contrary to the official conciliatory tones that come out of Beijing.

But this isn’t just about India. China’s relationships with all its neighbors – from Mongolia to Vietnam – mirror the same carrot-and-stick reality. Early this year, the Chinese began expanding islands in the disputed South China Sea, drawing the ire of the ASEAN. Beijing calmly played it all down, with sweet words of friendship. While states in the ASEAN have long been demanding a multilateral negotiation to the dispute, Beijing has resolutely stuck to its claims, building islands and sending out naval fleet into the sea from time to time.

China’s hostile and imperial attitude towards its neighbors is almost medieval in nature and most unbecoming of an aspiring superpower in the 21st century. Yet, many believe, with good reason that a muscular foreign policy serves Beijing well – internally. With income levels rising among the Chinese middle class, expressions for greater democratic freedom are beginning to get more vocal. In Hong Kong, last year, pro-democracy protests brought the city to a standstill, with separatists in faraway Xinjiang and Tibet granted their support to the movement. To divert attention away from internal threats, Beijing began finding a common ground to unite its people: external threats. By painting its neighbors as imminent dangers to the Chinese people and their very existence, Beijing has managed to justify the need for a strong Chinese state. The recent talk among the Chinese on Japan’s aggression during World War II is, perhaps, part of that threat propaganda – and so are the vicious opinion pieces on India’s claim over Arunachal Pradesh.

Such hostility leaves little room for China’s neighbors to engage with Beijing. Yet, all of China’s neighbors stand to benefit from closer economic and trade ties with Beijing. In the case of India, the benefits are mutual. With the trade deficit widening against India, New Delhi is increasingly in need of Chinese investments inside India. And with the Chinese labor force growing older and more expensive with each passing year, Chinese enterprises are in need of cheaper and younger workers from across the border in India.

For New Delhi, engagement with Beijing can’t come at the cost of letting its guard down on glaring political differences, and the answer to balancing the two is a ‘bottoms-up, forward policy’ – designed to look forward, rather than back. If New Delhi and Beijing can’t collaborate more meaningfully with each other, then their people, businesses and provinces should. Geopolitical differences are for mandarins in the capital city – not the common man on the street. The average Indian and Chinese student, businessman and professional have much to gain through people-to-people exchanges and investments. This is why Prime Minister Modi chose to set aside his geopolitical differences with Beijing for the while and supervised the conclusion of business deals worth $22 billion, along with cultural and educational parks in Bengaluru and Beijing.

Bottoms-up engagement with China has one other, less obvious advantage for New Delhi; it quietly fights the anti-neighbor propaganda machine set alive by Beijing at home. By fostering closer relations between people and businesses, India can thwart any anti-India sentiments among the Chinese people, thereby playing down the idea of New Delhi being a danger to the Chinese.

India must engage with China – for the good of their own people and that of the larger region around them. But New Delhi can’t do so as recklessly in good faith as it had done in the past. This is one bilateral relationship that has to be driven from the bottom rather than from above.