Nehru’s Perfidy Over Tibet In 1950

An extract from “Asia Reborn:A Continent rises from the ravages of colonialism and war to a New Dynamism”, by Prasenjit K Basu (Aleph, 2017)

Burma was the first nation outside the Soviet bloc to recognize Mao’s regime as the legitimate government of China (on 9 December 1949), and India was the second (on 30 December 1949), followed by Pakistan five days later. Soon after India accorded diplomatic recognition to Mao’s government, it began to periodically denounce Nehru as a hypocritical imperial lackey. In January 1950, Mao’s regime announced that its key unfinished tasks for 1950 included the ‘liberation’ of Tibet, Hainan Island and Taiwan.

‘Liberation from whom and what?’ the Tibetans plaintively but quite pointedly asked, ‘Ours is a happy country with a solvent government.’ A representative of the Manchu regime (almost always a Manchu rather than a Han Chinese) had been stationed in Lhasa for about two centuries until 1910 (but there had been no representative, and no relationship, between Tibet and the Ming or any previous Han Chinese dynasty). Even the Manchu representative was essentially an ambassador, although the Qing court—in the imperial manner to which China’s courts were accustomed—designated Tibet’s rulers as tributaries rather than allies or foreign powers. By 1950, however, Tibet had been completely independent for forty years—with no Chinese diplomat, sentry, postal system, language, newspaper or any other trappings of Chinese-ness visible in Lhasa or elsewhere in Tibet.

India and Nepal had always treated Tibet as an independent country, and it was only Curzon who had introduced the notion of ‘suzerainty’ into discussions about Tibet’s relationship with the Manchu regime (uncritically labelled ‘Chinese’). Matters were somewhat complicated by the fact that the KMT had used Tibetan (Khampa) warriors in its last stand in Sichuan (the western part of which was, in any case, part of the ‘Inner Tibet’ that the Qing dynasty had annexed in its final decade, the rest of Inner Tibet being the vast, beautiful plateau of Qinghai sometimes labelled ‘Shangri-la’).

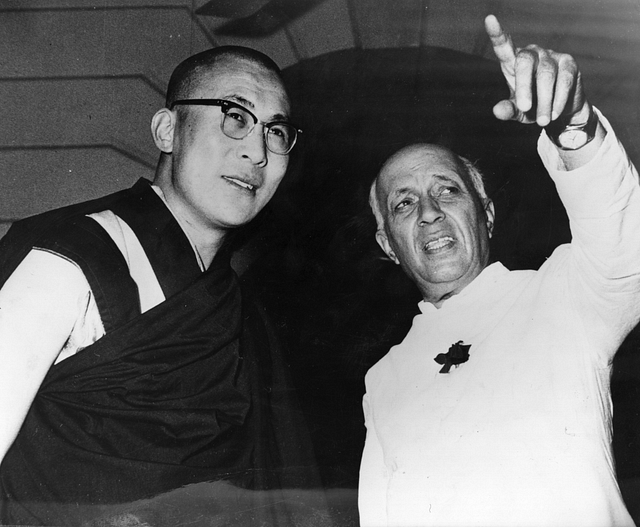

The fourteenth (and still current) Dalai Lama was not quite fifteen years old, but he urged his government to engage global opinion, to counter Communist China’s claim that Tibet was part of China or that somehow it needed to be ‘liberated’. In particular, Tibet sent letters to the US, UK and India. Nehru, who had invited a Tibetan delegation to the Asian conference of March 1947 now began taking a more conciliatory approach towards China; when repeatedly asked about Tibet, he maintained that India had good diplomatic relations with Tibet and China, but by April 1950 was beginning to use the word ‘suzerainty’ to describe China’s claim over Tibet. (That modern international law does not acknowledge any such concept as ‘suzerainty’ did not appear to give Nehru pause.) Nehru also kept assuring India’s press and Parliament that India’s traditional rights in Tibet would be maintained under his formulation of Chinese suzerainty over Tibet.

Ironically, China had no real access to Tibet at the time, and India was the only nation that had extensive representation in Tibet (including at Lhasa, Shigatse, Yatung and Gyantse); when a delegation from Beijing travelled to Lhasa in March 1950, they came via Calcutta, then Kalimpong (in India’s Darjeeling district) before entering Tibet from the south. The Americans were keen to support Tibet’s claim to sovereignty but needed support from India (or possibly Nepal) to solidify the claim. But the proto-communist Nehru (who believed, in his simple heart, that communism was the wave of the future, and the forces of history would inevitably lead to the triumph of communism) contemptuously brushed off the American offer of support. Nehru told his cabinet that it was not possible for India to help Tibet fend off the well-armed PLA (but he did not address the question of whether American support could have augmented the military potential of a combined effort). The Tibetans were on their own, and hence highly vulnerable, having neglected any military preparation during their forty years of full independence.

China, while assuring India that it could retain its traditional rights within Tibet, began pressuring the Tibetan government by late September with a set of ‘three demands’, the first of which was to accept that Tibet was part of China. Accepting these demands would allow the ‘peaceful liberation’ of Tibet! The Dalai Lama was willing to discuss the other two terms, that China would control Tibet’s trade and would oversee its military, but refused to accept the first. And the Tibetans maintained that since there were no foreigners (apart from a single German and a single Briton) in Tibet, there was no need to ‘liberate’ Tibet from imperialist control and certainly no need for any Chinese troop presence in Tibet.

The leader of the Tibetan delegation asserted quite rationally: ‘Tibet will remain independent as it is at present, and we will continue to have very close “priest-patron” relations with China. Also, there is no need to liberate Tibet from imperialism, since there are no British, American or KMT imperialists in Tibet, and Tibet is ruled and protected by the Dalai Lama (not any foreign power).’ The ‘priest-patron’ relationship is what Tibet had with the Manchus and the Mongols (but, pointedly, not with the Ming or any other Han Chinese dynasty). It was based on mutual respect, with the Mongols and Manchus respecting the spiritual leadership of Tibet in exchange for some temporal rights. Tibet’s tragedy was that the world did not pay attention then, and has not paid much attention since.

Mao knew that, although the PLA was a well-oiled machine, it did not have the ability to fight a war on the high plateau of Tibet should India seriously seek to engage militarily. But it was clear to him (from Zhou Enlai’s initial contacts with Nehru) that there was scant chance of India intervening. So, despite some stout resistance from Khams in the area, Mao sent the PLA into battle across the Jinsha River on 7 October and, after some fierce fighting, the PLA captured the eastern Tibetan town of Chamdo on 19 October 1950. News of this fighting was kept very low-key, and only dim reports appeared in India about a fortnight later, while the rest of the world remained largely oblivious.

Nehru, fully engaged in his flights of fancy as an ‘honest broker’ between the two Koreas, was still insisting that the Chinese would adopt nothing but ‘peaceful means’ while dealing with Tibet. If he had any intelligence reports about China’s invasion, he kept them very much to himself until it was too late. When El Salvador introduced a resolution on behalf of Tibet into the UN, Britain and India shamefully thwarted any discussion of it. (This was especially ironic since the PRC, although recognized by Britain and India, was not a seated member of the UN at the time and regularly launched verbal attacks on Britain and India as arch imperialists.)

On 7 November 1950, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, India’s home minister, wrote to Nehru, ‘the Chinese government have tried to delude us by professions of peaceful intentions.... the final action of the Chinese, in my judgement, is little short of perfidy. The tragedy of it is that the Tibetans put faith in us; they chose to be guided by us; and we have been unable to get them out of the meshes of Chinese diplomacy or Chinese influence.’ Patel added tellingly, ‘We had a friendly Tibet which gave us no trouble.... We seem to have regarded Tibetan autonomy as extending to (an) independent treaty relationship. The Chinese interpretation of suzerainty appears to be different. We can, therefore, safely assume that very soon they will disown all the stipulations which Tibet has entered into with us in the past.’ This was amongst Patel’s last communications with his colleague; his health was deteriorating fast, and he died on 15 December. But his warnings proved prescient.

The fourteenth Dalai Lama was enthroned on 17 November 1950, and soon afterwards agreed to send a delegation to negotiate with Beijing. The delegation, far from negotiating, was faced with a seventeen-point set of demands that it was obliged to accept, and given no opportunity to communicate with their government back in Lhasa. After six months of effectively being held hostage, the delegation agreed to the seventeen points on 23 May 1951.

It was the first time any representative of Tibet had ever agreed to accept China’s sovereignty in any form over Tibet, although the Tibetan government (and its leader the Dalai Lama) had not accepted this. There was little to distinguish this ‘acceptance’ from Korea’s acceptance of Japanese sovereignty over Korea in 1909-10; the acquiescence of Teddy Roosevelt had made Japan’s annexation of Korea possible in 1910, and Nehru’s acquiescence similarly allowed China to annex Tibet by October 1951 (when its troops entered Tibet).

The Dalai Lama first sounded out Nehru on the possibility of obtaining political asylum in India in 1956 and was strongly rebuffed. Eventually, amid the brutal suppression of the Tibetan uprising of March 1959, the Dalai Lama (still only twenty-four years old) escaped on foot to Assam, and was finally granted asylum in India, where he established a ‘Little Lhasa’ at Dharamsala in Himachal Pradesh, just south of Ladakh, the region that Ranjit Singh and Gulab Singh had annexed from Tibet in the nineteenth century and that is today a redoubt of Buddhism in India.

In 1962, an Indian Army that had been starved of funds by the leftist defence minister, Krishna Menon, was given a bloody nose by China’s PLA. My newly-married mother was amongst many thousands who donated her jewellery to India’s cause but was told to flee north Bengal, as the Chinese swarmed into Assam before suddenly withdrawing after ‘teaching India a lesson.’

Prasenjit K Basu runs an independent economic consultancy focusing on Asia. He is a regular commentator on Asia at the BBC, Channel News Asia, CNBC, Zee-Business and NDTV-Profit, and has written commentaries for the Financial Times, International Herald Tribune, India Today, BBC Online, The Statesman and IndiaSe.