Nixon? Surely Not

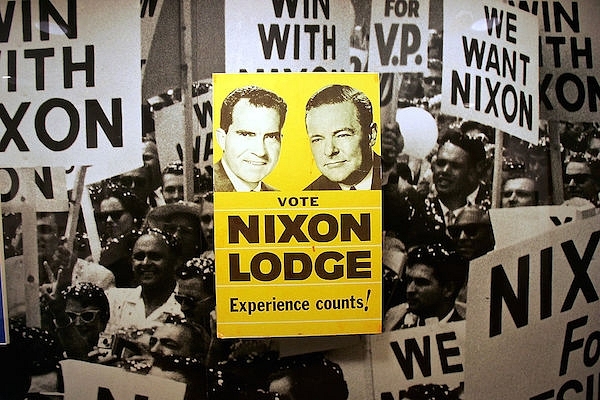

The model that the Donald Trump campaign is using for its public image, messaging, and policies was the one pioneered by Richard Nixon in 1968.

It’s a perfect time to remember what that Nixon generation learned: regardless of ideology, absolute power corrupts absolutely.

If you have followed the Republican trajectory over the last year, perhaps this will not surprise you. And maybe you discerned this last week when “Law and Order” became another official Republican campaign slogan, alongside “Make America Great Again.”

As it turns out, the model that the Donald Trump campaign is using for its public image, messaging, and policies was the one pioneered by Richard Nixon in 1968. Trump’s campaign manager Paul Manafort confirmed it.

Then the candidate himself agreed. “I think what Nixon understood is that when the world is falling apart, people want a strong leader whose highest priority is protecting America first,” Trump said. “The ’60s were bad, really bad. And it’s really bad now. Americans feel like it’s chaos again.”

Nixon Was the Turning Point

Nixon was a remarkable case. His public credibility was built by his big role in the 1948 congressional hearings that pitted State Department Official Alger Hiss against Whittaker Chambers. Nixon was then a congressman from California and a key player on the House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC). He publicly demonstrated Hiss’s Communist Party connections, and thereby, became a hero to the anti-communists of that time.

The event became the cornerstone of Nixon’s entire career, establishing him as the leader of the anti-leftist faction of the party. Based on this reputation, he went from the House to the Senate in 1950, to the Vice Presidency in 1952, and finally the Presidency in 1968. Upon his election, hopes were high among the libertarians of the time that he would perhaps work to dismantle the welfarism and warfarism of the Lyndon Johnson era.

I recall my father telling me about his own feelings at the time. “I never trusted Nixon,” he told me years later. “But we shared the same enemies. At the time, that was enough for me.”

Even in those days, the Republican Party was a coalition of disparate groups: foreign policy hawks, law and order conservatives, and the libertarian-minded merchant class that was sick of government spending, inflation, taxation, and regulation. The political priorities of the groups were in tension, often in contradiction. Which would prevail?

As it turned out, Nixon would devastate the anti-communist crowd by opening up diplomatic relations with China. But that was nothing compared to his complete betrayal of the libertarians, who had reluctantly supported him. He began the drug war that was specifically structured to harm blacks and hippies. He ordered IRS audits of his enemies.

Nixon closed the gold window and officially put the monetary system on a paper standard, thus, realizing the dreams of decades of Keynesians and backers of big government. He pushed the Fed for more inflation. He founded the Environmental Protection Agency, which has harassed private property owners ever since.

Most egregiously and shockingly, on 15 August 1971, Nixon announced to the nation a policy that hadn’t been experienced since World War II. It was like a scene from Atlas Shrugged. “I am today ordering a freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States,” he said. After the freeze, all price increases were to be approved by a pay board and a price commission.

This was the event that led the libertarians to gain a heightened consciousness of the task before them. What had previously been a loose association of intellectuals and a few other writers became a mass movement of students, donors, organizations, publications, and activists. The Libertarian Party was founded. Reason Magazine, founded as a mimeographed pamphlet in 1968, became a real magazine with an actual publication schedule. Ron Paul, under the intellectual influence of the Foundation for Economic Education, decided to enter public life.

Murray Rothbard captured the spirit of outrage that gave birth to the libertarian movement. He wrote the following in the New York Times on 4 September 1971:

On Aug. 15, 1971, fascism came to America. And everyone cheered, hailing the fact that a “strong President” was once again at the helm. The word fascism is scarcely an exaggeration to describe the New Economic Policy. The trend had been there for years, in the encroachment of Big Government over all aspects of the economy and society, in growing taxes, subsidies, and controls, and in the shift of economic decision-making from the free market to the Federal Government. The most recent ominous development was the bailout of Lockheed, which established the principle that no major corporation, no matter how inefficient, can be allowed to go under.

But the wage-price freeze, imposed in sudden hysteria on Aug. 15, spells the end of the free price system and therefore of the entire system of free enterprise and free markets that have been the heart of the American economy. The main horror of the wage-price freeze is that this is totalitarianism and nobody seems to care…

The worst part of our leap into fascism is that no one and no group, left, right, or center, Democrat or Republican, businessman, journalist or economic, has attacked the principle of the move itself. The unions and the Democrats are only concerned that the policy wasn’t total enough, that it didn’t cover interest and profits. The ranks of business seem to have completely forgotten all their old rhetoric about free enterprise and the free price system; indeed, The Washington Post reported that the mood of business and banks is “almost euphoric.”…

The conservatives, too, seem to have forgotten their free enterprise rhetoric and are willing to join in the patriotic hoopla. The New Left and the practitioners of the New Politics seem to have forgotten all their rhetoric about the evils of central control...

It was this article, and the events he described, that made the libertarians realize that they needed their own movement, something different from the left and right, and outside the Democrats and Republicans, each of whom represent their own kind of tyranny. Never again would they trust the promises of a “strong president.” Never again would they trust a mainstream party.

The experience with Nixon taught those who seek more freedom that there is a huge difference between merely hating the left and actually loving liberty. The lesson was burned into the hearts and minds of a whole generation: to see your enemies crawl before you is not really a victory. The only real victory would be freedom itself. And to love liberty is neither left nor right. Libertarianism is a third way, a worthy successor to the great liberal movement from the 17th to 19th centuries, the movement that established free trade, worked for peace, celebrated prosperity through freedom, ended slavery, liberated women, and universalized human rights.

The realization marked a new era in American political life.

Then There Was Watergate

When Nixon was finally driven out of office following the Watergate scandal, conservatives wept. But the libertarians, having now developed a sense of their task quite apart from the rightest cultural and political agenda, cheered the end of the cult of the Presidency. By then, Nixon had become their bete noir.

Rothbard wrote:

It is Watergate that gives us the greatest single hope for the short-run victory of liberty in America. For Watergate, as politicians have been warning us ever since, destroyed the public’s “faith in government” – and it was high time, too. Watergate engendered a radical shift in the deep-seated attitudes of everyone – regardless of their explicit ideology – toward government itself. For in the first place, Watergate awakened everyone to the invasions of personal liberty and private property by government – to its bugging, drugging, wiretapping, mail covering, agents provocateurs – even assassinations. Watergate at last desanctified our previously sacrosanct FBI and CIA and caused them to be looked at clearly and coolly.

But more important, by bringing about the impeachment of the President, Watergate permanently desanctified an office that had come to be virtually considered as sovereign by the American public. No longer will the President be considered above the law; no longer will the President be able to do no wrong. But most important of all, government itself has been largely desanctified in America. No one trusts politicians or government anymore; all government is viewed with abiding hostility, thus returning us to that state of healthy distrust of government.

It’s almost a half century later and the Republicans have once again chosen a man who is loved mainly because of the people he hates and those who hate him back. And once again, we are being told that greatness, law, and order should be the goal. Once again, the right is defining itself as anti-left while the left is defining itself as anti-right, even while both favor centralist and nationalist agendas.

It’s a perfect time to remember what that Nixon generation learned: regardless of ideology, absolute power corrupts absolutely. Even 20 years later, libertarians were highly skeptical of Ronald Reagan for this reason. It wasn’t until he showed himself to be a very different kind of candidate than Nixon— Reagan was very clear that the real enemy of the American people was government itself— that libertarians went along.

Regardless of the personalities ascendent at the moment, the real struggle we face is between the voluntary associations that constitute the beautiful part of our lives, on the one hand and, on the other, the legal monopoly of violence and compulsion by the institutions of the state, which lives at the expense of society.

If you don’t like government as we know it, you need to decide why. Is it because you believe in a social order that minimises coercion and unleashes human creativity to build peace and prosperity? Or is it because you think the wrong people are running it and we need a strong leader to put them in their place? This is the major division in politics today.

This article was originally published on Foundation for Economic Education and has been republished here with permission.