What The New Geopolitical Global Order Looks Like

With the relations between the US and Russia plunging new lows, suggesting the start of a new cold war, the ceaseless sectarian conflict across the Middle East and the rise of the belligerent China, the global order is rearranging itself.

The collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR, in 1990 was as significant for the global order as the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 and, indeed, the decisive intrusion of Stalin’s Soviet Union as a superpower in 1945. The Soviet military might had reached beyond the Elbe, into Berlin, and created a wider global footprint, in the shape of the emergence of Mao Zedong’s China and Fidel Castro’s Cuba. It was of course immediately contested by the United States (US) and its Western allies. Thus began the Cold War and a constant violent struggle for position, from Asia to Africa. Much blood was split, mostly of the poor, their fate reduced to statistics.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s momentous decision in 1990 did not merely amount to throwing in the towel in the Cold War but led to a dramatic retreat from critical strategic positions in Europe. He apparently did not reflect on the serious consequences that faced his country. The US responded with feigned goodwill and alacrity, proclaiming a new era of amity, a post-Cold war peace dividend of reduced defence spending and respect for Soviet security interests. None of this came to pass. The US, the overwhelmingly dominant power that remained intact, chose a global surge to reap the fruits of victory in the Cold War. It sought to consolidate its global position as well as extend and deepen its influence across the world.

A most audacious and almost successful policy the US government adopted was to ally with newly emerging robber barons in post-Soviet Russia to promote favoured nominees. It also sponsored interference through Bretton Woods institutions, in the name of economic reform, to demolish the post-Soviet national economy. There could hardly have been a better confirmation of the inherent complicity that exists between supposedly neutral academic experts and government agencies whose bidding they eagerly execute. Much communist-era national assets, painfully accumulated over two generations, was looted by criminal insiders, who then shamefully flaunted their ill-gotten wealth while the average Russian struggled in worsening poverty.

The next move by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), reneging on assurances given when Russia withdrew from Eastern Europe, was to quickly expand itself as close to the Russian border as possible. Former Eastern European communist neighbours of Russia were offered the irresistible carrot of European Union (EU) membership. It meant significant economic aid, market access and free movement for their underpaid labour into more advanced EU neighbours. It was a no-brainer for these former members of the Warsaw Pact to join the EU, suffering catastrophic socio-economic dislocation in the aftermath of the Soviet retreat and the dismantling of their planned economies. Many were also inevitably cajoled into NATO membership, and the US began to patronise nationalist constituencies within these countries, easily arousing latent historical animus against their Russia neighbour. A renewed Cold War had commenced to deliver a coup de grace to a faltering Russia.

Yet, the anticipated free EU lunch ended up as complete domination of Eastern European economies by Germany. It also threatened to destroy countries like Latvia, its population mined by more prosperous EU countries like disposable raw material. In addition, attempts at regime change to install supine Eastern European leaderships, willing to do NATO’s bidding, prompted civil wars in some countries. Some nations broke up, Ukraine being the most recent victim of the cynical stratagem. But it didn’t all go according to plan, and a massive campaign was launched in pique, manfully taken up by an incorrigibly anti-Russian British media, to demonise Russia and its political leadership. As NATO forces moved closer to the Russian border and its territorial waters, an absurd chorus was instigated to accuse Russia of threatening the very Western forces moving purposefully towards it.

US machinations in Europe, enthusiastically supported by Britain, France and, with only slightly less conviction, Germany, were followed by invasions of Afghanistan and the Middle East. The 9/11 terror attacks provided the excuse for an all-out neocons-inspired Roman conquest, first overthrowing Saddam Hussein of Iraq and then Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, to shocking whoops of joy from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at his brutal public execution. The Gaddafi thorn on the side of US plans to install military bases in Africa had been removed. The Orange Revolutions patronised by the US to effectively channel popular protest against incumbent Eastern European governments also duly unfolded across the Middle East, in the shape of an Arab Spring. None lived up to the media-promulgated hype about the spread of human rights and democracy, succumbing successively to authoritarian governments or outright military dictatorships. A naive public was thoroughly duped and all was well under the sun.

The unfinished Middle Eastern agenda is the horrendous Shia-Sunni sectarian conflict that Western intervention unleashed across the world, from Pakistan to the entire Middle East. The shocking Islamic State phenomenon is only a spin-off that didn’t quite go according to plan, to have it focus primarily on overthrowing the Bashar al-Assad regime of Syria. Russian refusal to abandon the admittedly murderous President Assad, lacking an iota of respect for basic human rights, was the product of a new post-Cold War that the geopolitics of Russian reluctance to persist with the interminable flight Gorbachev had presided over. Vladimir Putin’s Russia refused to concede total rout and Russia’s elimination as a major player in the international arena. It is noteworthy that the contemporaneous US-Iranian engagement is merely a tactical ploy. There is an expectation that Iran’s deeply unpopular and brutal clerical rulers will be overthrown once the US bogey to justify their continuance weakens. In the meantime, one of the world’s worst violators of human rights and sources of global terror, the bloodthirsty Saudi royalists, were easily re-elected to the United Nations Human Rights Council, with Western backing, while Russia was ejected.

Some negligible issues with recalcitrant neighbouring Latin America governments are being addressed by the US through local proxies in Brazil and Venezuela. The unceremonious demise of quasi-nationalist populist elites, failing to comprehend the conditionality of their own sovereignty and the sheer weight of US economic interests and political prowess, was facilitated by unreconstructed, local comprador elites. Cuba’s economic absorption, since its recent opening to the wider world, by the US mainland will occur in short order by virtue of the massive disproportion in their relative sizes and will restore its historically subaltern relationship.

The US is also creating military bases across Africa, though allies like France are sharing in the spoils by, for example, usurping the uranium deposits of Niger in West Africa. The resumption of imperial control of Africa is being accomplished through the age-old ploy of accentuating local societal fissures and mobilising factions against each other. The end of the bipolar Cold War freeze on global imperial designs is allowing their resumption, echoing the history of several past centuries.

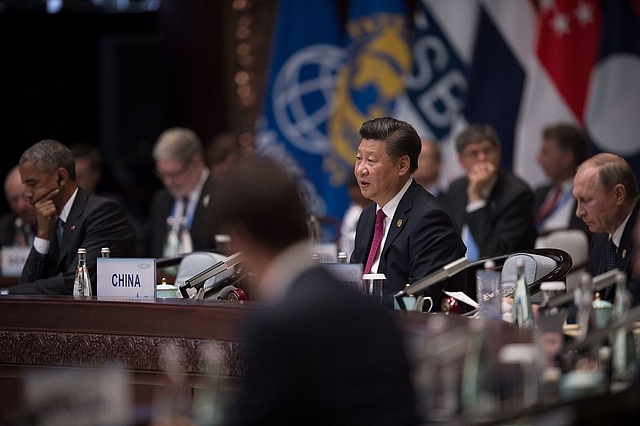

The elephant in the room remains a crudely ambitious China, claiming vast swathes of the high seas and nurturing the two worst rogue states in the world, North Korea and Pakistan, fuelling their belligerence. China is no military threat yet to the US in Asia, certainly as a nuclear weapons state. There are also indications it may suffer serious setback owing to underlying economic instability that may arrest its apparently irresistible rise. And the US is busy organising a coalition of Asian powers to curb Chinese overreach. This medley of Asians powers includes Japan, India and Vietnam, all of who have territorial and military disputes with China. However, ultimately, the US is likely to negotiate an Asian condominium with China from a position of strength that now includes control over Nepal and its rapid transformation into a frontline military base for intervention in Tibet. Such a negotiated accord with China will occur at the expense of erstwhile Asian allies of the US. But such is the nature of international relations, in which permanent interests alone endure.