Business

Where Is USD-INR Likely To Be In 2047?

Harsh Gupta Madhusudan

Feb 15, 2023, 02:46 PM | Updated 02:45 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Currency dynamics can be a niche area even within the broader macro-economic field, and is one of the topics that I have been fascinated with.

I have written about it in the past, and intend to again. Understanding this better can help both policy makers and investors.

Since everyone is talking of the symbolically important date of 2047 (being the 100th year of Indian independence), let us try to walk through how to think about the USD-INR exchange rate then.

It is another matter that I think the rupee will be a hard currency, indeed a reserve currency, by then (hence, others will also benchmark their currency against ours) but there will be many cycles and slips between then and now, so let us play this out.

India’s average per capita income at current USD-INR rates is less than 1/30th of the US. Its cost of living is around 1/4th of the US. Adjusted for purchasing power, Indian incomes are say 1/8th.

Now let us think for a moment Indian incomes converge with the US in the mid-2060s. Some may think they may never converge, and I may think they may converge a bit earlier, but let us continue with this thought experiment to understand how to think about USD-INR’s trajectory.

So 2023 to 2065 is 42 years. ~8x convergence in that period (Indian incomes catching up with American ones) means relative doubling every 14 years (42/3 = 14 years, 8 times being 3 doublings).

That means a relative faster growth in India of about 5 per cent — by the so-called rule of 70, a rough rule of thumb.

Which means if India and America have roughly the same population growth rates in the foreseeable future of say 0.5 per cent and if American real per capita income growth is at 1.5 per cent, then Indian real GDP is likely to grow at 0.5 per cent + 1.5 per cent + 5 per cent = about 7 per cent on average.

These numbers sound plausible. We can disagree and there is detail as well as nuance here, but let us proceed.

If this broadly happens, then as incomes converge between countries (with large populations) so should the cost of living. Which means that Indian cost of living should have a higher appreciation of 3-3.5 per cent per year on average, compared to the American one for the same nominal exchange rate (To be exact, 4^(1/42) = 3.36 per cent).

Of course the nominal exchange rate is not likely to be the same. But one way to understand real appreciation is, it is equal to the relative increase in cost of living provided the nominal rate is the same.

When that is the case, the country with the higher cost of living increase is said to have seen real currency appreciation. Its exports are likely to be less attractive and imports more attractive — unless it has seen a productivity increase in the tradable sector, which is what should cause any sustainable real appreciation in the first place. But I digress towards nerd-land.

Now to go from the real appreciation of say 3 per cent for India, to the nominal rate in the future versus the dollar, one must predict or guess the inflation differentials.

There is again a lot of devil in the detail, but let us assume the difference is 2 per cent. India has a 4 per cent inflation target and the US has a 2 per cent target.

Last year, both did not meet their targets (America missed by much more), but going forward as the Indian economy further matures and America ages (again, many nuances here) — we can assume the difference to be 2 per cent.

Then the nominal appreciation is simply the real appreciation minus the inflation differential. Which is 3 minus 2 or about 1 per cent over the next ~20-50 years approximately speaking.

In my view, this is actually not aggressive at all as an estimate and not to mention that, in periods less than 20 years, the cyclical element is much more prominent than the structural one.

Still, even with this conservative appreciation in my view, the rupee should roughly be in the 60s when modern India turns 100, down (rather it should be “up”) from low 80s now. Of course, we are talking in terms of probabilities and scenarios here.

The more interesting and relevant number may be the 2030 one — and remember right now the cyclical tailwind for the rest of the decade is with the rupee.

I will conclude by saying that as growth differentials expand between India and the United States (a proxy for the global tech-economic frontier) and inflation differentials decrease or broadly remain stable, the extant through-cycle real appreciation of the rupee will turn into nominal appreciation.

We already see that in the data over the last 20 years and the underlying trend will likely accelerate.

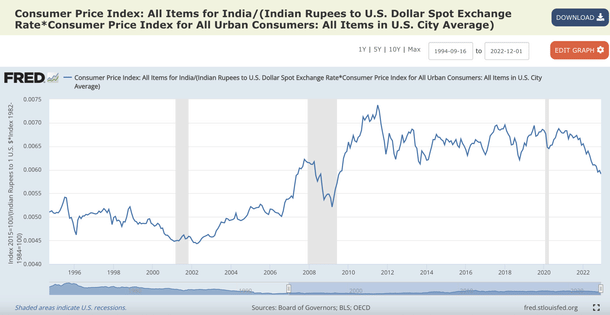

The graph below shows USD-INR appreciated for relative inflation differentials. We can see the structural real appreciation of the rupee over time, especially in a through-cycle sense over the last 20 years.

Remember that in 2002 to 2011, which was the last weak dollar cycle leg, the rupee remained nominally stable at 50 or below despite a huge inflation gap.

It is just that the pandemic and the war have delayed the next dollar weak cycle by a few years, but it is overdue — indeed, geopolitical and technological changes are likely to go in India’s favour.

Of course, nobody can predict the very short term. Happy arguing, investing and policy making!

Harsh is an investor, and the coauthor of two books - latest being 'A New Idea of India'.