Culture

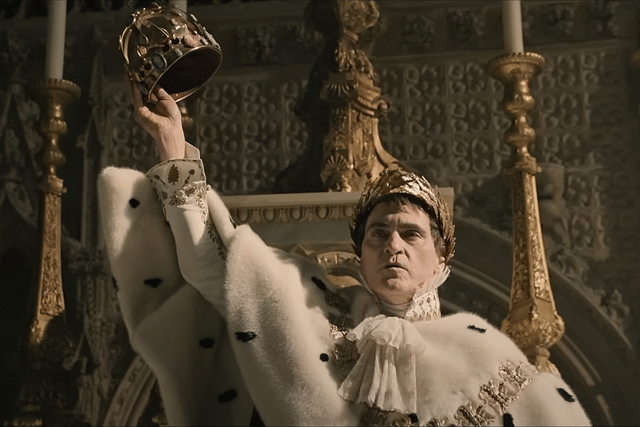

Napoleon Film Review: Ridley Scott’s Waterloo

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Dec 02, 2023, 12:07 PM | Updated 12:07 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Napoleon Bonaparte is probably the only major figure in world history to rise from total obscurity through sheer military genius to win his nation twice, be crowned emperor twice, lose his crown twice, nearly conquer a continent twice, and be exiled back to obscurity for his efforts twice.

His is a remarkable story, breaking the glass ceilings of lineage and convention, to become Emperor of France, win battles any other general would have lost, and to write himself so forcefully into the chapters of history that his successes and failures are still studied with undying interest in the halls of public discourse, academia, and military staff colleges alike.

Is there another character who had it in him to destroy the very revolution which birthed his career?

Which war aficionado has not heard of Napoleon’s masterful recapture of the French port city of Toulon from the English — the one decisive, primordial act that established his credentials as a battle commander and brought him into the limelight of political stardom?

Historians and generals never cease to marvel at his ambitions, of capturing Egypt, Asia Minor, Russia, and even the route to India, to bring England to her knees — without a navy?

Where is the military historian — amateur or professional — who cannot reel off the names of Napoleon’s many campaigns and battles?

The Battle of Tarvis, 1797, where he defeated the Austrians; Marengo, 1800, when he slaughtered the Austrians, again; the subsequent treaty of Amiens in 1802, which allowed him to make the Louisiana Purchase; Austerlitz in 1805, where he weakened his flanks on purpose to riskily draw his enemy into a fatal trap; and Corunna, 1809, during the Spanish campaign, when he defeated the English comprehensively.

Of equal historical significance are his failures: the French navy’s defeat at the hands of the British Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, and then again at the battle of Trafalgar in 1805; and, of course, Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815 by the Duke of Wellington (with some help from the Prussians).

There is enough primary source material on Napoleon to fill a library. Yet, alas, even with so much information available on hand, with such rich detail, director Ridley Scott has squandered a brilliant opportunity to make a memorable epic, failing to match the standards he set with masterpieces like Alien, Blade Runner, Gladiator, and Black Hawk Down.

What is the basic problem with the film?

Sadly, Napoleon is less of the epic it could have been and more of a tedious, soporific conflict between unfettered, self-indulgent movie-making and spectators’ yearnings.

Scott goes the psychoanalyst route, delving into the emotional motivations of the man. This approach clashes with the viewers’ expectations, and hopes, that they might understand Napoleon’s military mind.

After all, audiences certainly didn’t cough up the big bucks at plush multiplexes to get 160 mind-numbing minutes of morose narrations of letters between Napoleon and his wife Josephine. No! They are in the theatre to try and learn how a man repeatedly turned defeat into victory, motivated his troops to overcome incredible rigours, and earned the undying loyalty of men who marched through hell and back for him.

Another inexplicable facet of the film is that Napoleon’s entire Egyptian campaign of 1798-1801 is reduced to a few brief scenes with the Pyramids in the backdrop, and one in which he comes face to face with the mummy of an Egyptian Pharaoh.

This bit is an unfortunate condensation, since Napoleon’s army carried a sizeable contingent of scientists and scholars.

The famous mathematician Joseph Fourier did most of his work on heat during this campaign. This was also when the first plans for the Suez Canal were prepared. The printing press was introduced to the world by the French through Egypt. And it was then that Pierre-François Bouchard discovered the Rosetta Stone — a path-breaking event that led to the deciphering of ancient Pharaonic hieroglyphics.

The film, apart from entirely glossing over the critical French loss to the British Navy at the Battle of the Nile, and Napoleon’s victory over the Ottomans at the Battle of Aboukir Bay, also introduces an historical irregularity: it portrays Napoleon’s abrupt, unauthorised return to Paris in mid-1799, which then led to a French defeat by the British, as a result of having learnt of his wife Josephine’s infidelities, rather than the truth, which is that he felt he had accomplished as much as he could in Egypt and now needed to return home.

This event would have brought out the whimsicality in the man, which conflicted with his military and political greatness, a factor which showed itself again, disastrously, in 1812 in Russia when he foolishly sought to pursue the Russian Tsar from Moscow to St Petersburg in the midst of winter, and which eventually let to the decimation of his army and his first exile to the island of Elba.

It is, no doubt, Scott’s prerogative to delve into the mind of the man, but to have done it to such an extent that he sadly reduces Napoleon to a caricature is a directorial no-no, and a discredit to the subject.

Alas, as a result, Scott’s Napoleon is pigeonholed for much of the film into a brooding, quirky man, who was driven more by his love for Josephine, an obsessive desire for an heir, and an uncontrollable libido, at the cost of everything else he achieved, and squandered.

This choice is regrettable because, while a talented filmmaker like Scott had the brilliant opportunity to craft a magnificent epic, a cinematographic Austerlitz if you will, he has instead chosen to compose a directorial Waterloo.

We can only hope that, just as Napoleon recovered from the humiliations of his unilateral departure from Egypt, by seizing power and becoming ruler of France, and then winning the battle of Marengo, Ridley Scott, too, recovers from his self-inflicted blunders and goes on to become the king of cinema again.

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.