Books

Book Review: Building A Case For The Emergence Of A ‘New Consensus Figure’ In Narendra Modi

Dr Anushree

Mar 21, 2024, 04:16 PM | Updated 04:19 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

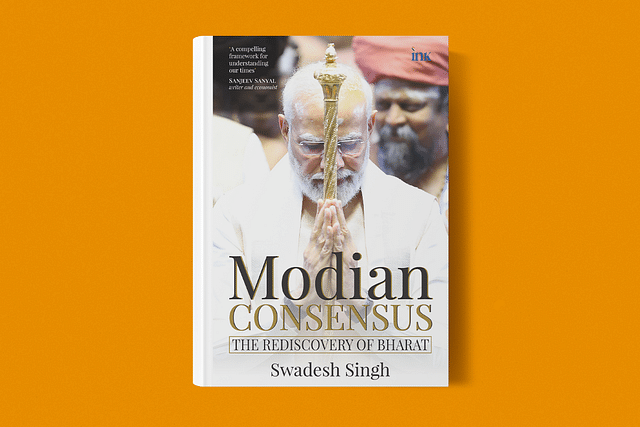

Modian Consensus: The Rediscovery Of Bharat. Swadesh Singh. BluOne Ink, 2024. Pages 304.

A few weeks before the general elections in India, the Time Magazine cover story of May 2019 by British-American Journalist Aatish Taseer, called Narendra Modi as the ‘divider-in-chief’.

However, just a few days later, the same magazine celebrated his thumping electoral victory in another article titled, ‘Modi has united India like no Prime Minister in decades’ by Manoj Ladwa.

The persona of Modi is such that his admirers and detractors are constantly engaged in building narratives around his speeches, policies, programs; some hinting at fissures, while others insinuating at the emergence of a consensus under his leadership.

One such narrative that attempts to theorise (150 years of) Indian politics vis-a-vis phases of consensus emerges in a recent book ‘Modian Consensus: The Rediscovery Of Bharat’ by academician Swadesh Singh. This is Singh’s second book in a row, the previous one being ‘Ayodhya: Ram Mandir’ (Rupa, 2024) on the Ayodhya Ram Mandir movement.

Modian Consensus running through 10 chapters divided into three sections categorises five phases of consensus namely: Civilisational, Gandhian, Nehruvian, Secular and the latest being the Modian. The beginning of this new phase in Indian politics under Narendra Modi’s leadership is characterised by three norms — welfare for all, assertive nationalism and cultural rootedness.

Singh claims that those who wish to gain electoral credibility and respectability in mainstream politics, including Modi’s opponents are bound to follow these norms. Modian consensus is however, not confined to the realm of politics, but has taken roots in the field of art, literature, cinema, culture and academics.

While the first section is devoted to the consensus in pre-independence and a few decades post-independence and includes two consensus figures, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Jawahar Lal Nehru, the rest two revolve around the Modian consensus.

One of the basic concerns of the book is to look for moments and phases in the political history of the country to counter the Western-driven distorted view of India and to present an alternative vision of ‘Bhartiya Rashtra’.

Nehruvian Consensus And The Secular Paradox

Singh presents an honest and unbiased account of the Nehruvian consensus, which revolves around the bulwark of socialism, secularism and non-alignment.

He presents him as an institutional builder who played a crucial role in developing the modern Indian state. He however, alleges that Nehru’s myopic vision, flawed political experiments and a distorted understanding of the Indian society cost the nation badly, whether it was the issue of Kashmir, China or the gaps in the five-year plans.

He considers the succession of Motilal Nehru by J L Nehru as the Congress President in 1929, as the first case of dynasty politics in the history of modern India, further perpetuated by Indira and her sons post-independence.

The Nehru-Gandhi family were able to establish their hegemony by establishing an educational system that disregarded India’s ancient civilisational values, by giving the mantle of education to left-leaning intellectuals.

While Singh acknowledges the initiatives like MNREGA and Right to Information by United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in its first term, their second term was defined by rampant corruption and confusion. Furthermore, 10 years of the Congress-led UPA rule highlighted the contradictions of the secular consensus, best defined as ‘pseudo-secular’ and appeasement politics.

The book vouches for ‘positive secularism’ as defined by Shri A B Vajpayee to mean ‘Sarva Dharm Sambhav.’

Modi Sarkar And The New Consensus

In the subsequent sections, Singh builds a case for the emergence of a ‘new consensus figure’ in Narendra Modi, first as the chief minister of Gujarat and later as the Prime Minister for two consecutive terms.

His ‘Gujarat model of governance’ based on agrarian growth, infrastructure development, promotion of solar power leading to double digit growth rate has been presented as ‘sarvasparshi’ and ‘sarvamaveshi.’

With Modi’s election as the Gujarat chief minister for the third time, a new term ‘pro-incumbency’ was added to the political lexicon. The 2014 presidential-style campaign of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) centered around Modi’s persona was owing to the fact that the popularity ratings of Modi (47 per cent) was way higher than the BJP (31-32 per cent).

The subsequent chapters in this section read like the report card of the two terms of the Modi government highlighting all his achievements in the domestic and international fronts including ban on triple talaq, scrapping of Article 370 and the construction of Ram temple.

The surgical strikes of 2016 and 2019 are being seen as the new strategy of offensive defence under Modi government’s assertive nationalism and ‘Nation first’ policy.

An alumnus of JNU, Singh uses his lived experience to reflect on the student politics on campus. He highlights the anti-national sentiments of some of the student wings of the ultra-left who vilify students of the opposite camp, whom Singh calls as nationalists.

Singh applauds Modi government for actualising Jan Sangh leader Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s philosophy of integral humanism by initiating and implementing several welfare schemes from Start-Up India to Jan Dhan Yojana and to the gigantic COVID-19 vaccination drive.

How did Modi fare on the cultural leadership front? Singh associates cultural rootedness with the faith in glorifying the ancient civilisational values and imbibing them into the modern system.

He gives several instances such as temple tourism, inauguration of Kashi Vishwanath Corridor, creation of a new ministry for AYUSH and the installation of the Sengol in the Indian Parliament to vouch for Narendra Modi’s cultural leadership.

An interesting question drawing the attention of readers in this section is, whether BJP and Modi’s quest for cultural rootedness should be seen as Hindu revivalism against the Muslims.

The author outlines BJP’s Muslim outreach programmes, especially its recent initiatives for the socially and economically backward Pasmanda Muslims, including women, to counter such narratives.

In the concluding chapter on the challenges to the Modian Consensus coming from the barriers of semantics, semiotics and context, Singh cautions about attempts by the ‘anti-Modi ecosystem’ to present doctored narratives against the Prime Minister and the need for the proponents of the Modian consensus to collaborate for an alternative discourse.

At the end, one finds Singh optimistic about the sustenance of the Modian Consensus and suggests setting-up of 'amrit lakshya' in amrit kaal to forge a fine balance between technology and human values.

The students of Indian politics must read this work to understand the emerging consensus in new Bharat, led by the cult of Narendra Modi. The work is beneficial for both, the supporters of Narendra Modi, as well as his detractors — who may take a leaf out of this book to understand the traits needed to claim grand legitimacy on the domestic and international front in such a short span.

The book takes note of the recent ‘Mood of the nation’ survey (India Today) respondent’s unhappiness with the unemployment situation during and post covid-19 pandemic.

Singh, however, posits it as a challenge to be overcome and not as a failure of the current regime.

This book appears as an affirmative response to the rhetorical question of the March 2012 issue of the Time Magazine, ‘Modi means business, can he lead India?'

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Dr Anushree is an alumna of Miranda House and JNU. She had previously taught at Zakir Husain Delhi College, and contributed on several socio-political issues for print media, journals and online platforms.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.