Books

Two Well-Researched Books Shatter Dravidianist Urban Legends And Anti-Brahmin Stereotypes

Aravindan Neelakandan

Apr 27, 2024, 06:59 PM | Updated Apr 28, 2024, 06:23 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

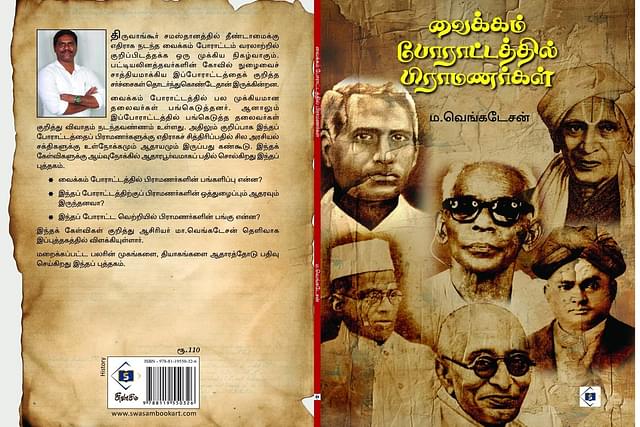

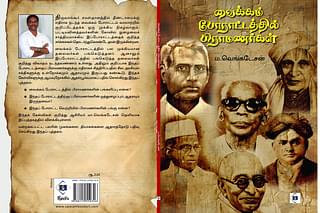

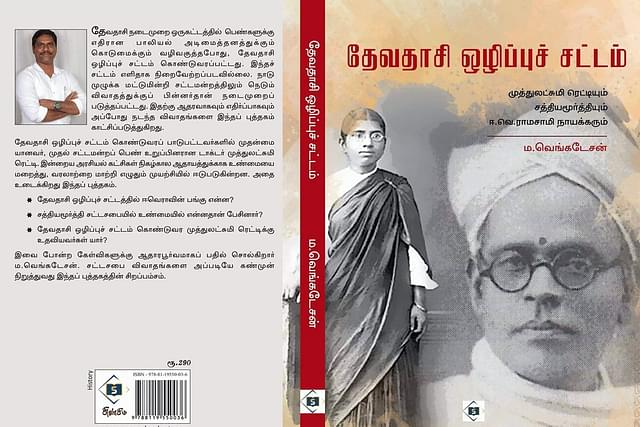

'Vaikam Satyagrahathil Brahmanarkal' (Brahmins in Vaikom Satyagraha). Ma. Venkatesan. Swasam Publications. Rs 110.

'Devadasi Ozhippuc Chattam' (Devadasi Abolition Law). Ma. Venkatesan. Swasam Publications. Rs 290.

Two recently released Tamil books challenge the Dravidianist narrative of social emancipation in southern India, particularly with respect to Tamil Nadu.

Ma. Venkatesan, the chairperson of National Commission for Safai Karamcharis, is considered as one of the most active of the chairpersons in the history of the commission, attending to the problems of the hygiene workers throughout India. But he is also a historian of a special kind.

He has documented through the last two decades the neglected dimensions of the social history of southern India.

In doing so he has burst quite a number of myths — particularly the myth of the landed caste Justice Party and Dravidianist movement, that they were in the forefront of bringing justice to oppressed Hindu communities.

A cultural historian of deep insights, he has brought out the deep spiritual ties that Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar had with the larger Hindu family of spiritual sampradayas including Buddhism, and also his patriotic dimensions in his much celebrated Tamil book Hindutva Ambedkar.

In 2024 he has come out with two important books.

The first one is about the role of Brahmins in the famous Vaikom satyagraha. The natural question is why Brahmins alone? Why not have books on the role of Nadars, role of Chettiars, etc?

The answer is important.

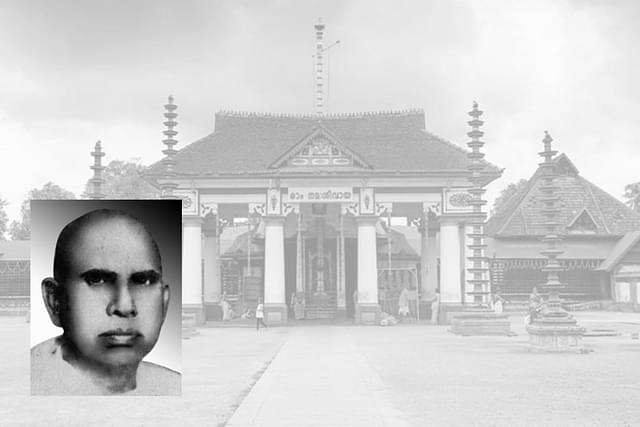

The satyagraha happened between 30 March 1924 and 23 November 1925. It was a movement that had its roots in the social implementation of Advaita Darshana as elucidated by Sri Narayana Guru.

Unfortunately, that narrative was hijacked by the Dravidianist movement which projected it as a fight against Brahmins by non-Brahmins.

The mapping of Hindu Dharma in general and the entire Brahmin community in particular to socially stagnant orthodoxy has been one of the favourite strategies of the Dravidianist forces in Tamil Nadu. The reality is that there were quite a number of Brahmins who went against their own caste leaders and at times even some religious leaders.

The spiritual inspiration for these Brahmins also came from the same Sanatana Dharma, which the socially conservative stagnant side called as their own. Particularly Vedanta and Advaita played an important role.

During the satyagraha, the socially stagnant orthodoxy asserted that the practice of restricting certain sections of the Hindu community from using the roads around the temple was a tradition initiated by Adi Shankara himself.

In their support, they produced a ‘Sankara Smriti’ supposedly written by the seer. This was shown to Mahatma Gandhi who had agreed that the satyagraha would be called off in this particular instance if it was a peculiar tradition there, even if he thought the tradition was based on wrong and unjust values.

But Gandhi ji had no literary knowledge of Sanskrit. It was a Nambudiri youngster, Krishnan Nambudri who went through the text and pointed out to Gandhiji the blatant grammatical errors and the sloppy style in which the text was written. He thus busted the claim that it was written by Adi Shankara.

Later, Krishnan Nambudri became a monk of Sri Ramakrishna Mission, named Swami Agamananda. Swami Agamananda played an important role in the upliftment of oppressed Hindu communities in Kerala. It was from his educational institutions that the first Scheduled Community entrant into civil services came.

The point is one should be very careful in distinguishing between crypto-casteists (like T M Krishna) and genuine Brahmins who fought for social emancipation against all odds because they were inspired by Sanatana Dharma.

Ma. Venkatesan's latest book is significant as it challenges negative stereotypes around Brahmins. It refutes the notion of alien Brahmins imposing their supremacy through religion and decadent social values.

The book highlights that the Dravidianist stereotype of Brahmins is akin to the Nazi caricature of Jews. At a time when the ruling dispensation in Tamil Nadu appears to endorse such hatred under the guise of social justice, this book emerges as a courageous voice against such animosity.

Equally important is the second book.

The legislative banning of the Devadasi system was an important milestone in gender emancipation. The system was originally designed with noble intentions.

But during the turbulent period of colonial wars, ongoing battles against Islamic colonialism, and the rise of feudal-like chieftains in southern India, it rapidly deteriorated into an exploitative practice.

This abomination, much to the satisfaction of colonisers and evangelists, was justified by those managing the temple institutions.

The fight against this system was championed by many reformers of the period. Among the fighters, the foremost name was that of Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy (1886-1968). She brought a bill in 1930 for the abolition of this system.

Dravidianist urban legends have it that it was E V Ramasamy (EVR), referred to by some as ‘Periyar’, who gave ideas to Dr Reddy to argue in the legislative assembly against one of the defenders of Devadasi system Sri Satyamurti, a Congress politician and conveniently a Brahmin.

Ma. Venkatesan in the book on the law abolishing the Devadasi system has torn into these urban legends with authentic information and data.

Actually, whenever Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy attacked social stagnation and its ill effects plaguing the society, she was careful to point out that genuine Hindu Dharma was not to be seen through the lens of social malice.

She spoke highly of Gargi and Maitreyi, the Vedic ideal of womanhood. She spoke of Sharada Devi and Sri Ramakrishna as the ideal Indian couple and quoted not EVR but Swami Vivekananda as the reference point for social emancipation.

Ma. Venkatesan has authored two books that remind us of the movements for social emancipation and the authentic Sanatana legacy within these movements. These books also debunk the pseudo-historical myths propagated by Dravidianists, who attempt to claim the legacy of social emancipation for themselves.

Swasam Publications, a publishing house that aims to bring a qualitatively better change in the intellectual and cultural landscape of Tamil Nadu, has brought out these two books.

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.