Books

Why Police Reforms Don't Take Off In India

Surajit Dasgupta

Jan 03, 2016, 07:00 PM | Updated Feb 24, 2016, 04:18 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

We are asking the powerful to rid themselves of power.

Today India is debating “intolerance” and, as a corollary, freedom of expression. But how can you express yourself freely if the threat to your life and property you thus invite cannot be neutralized by the police?

It cannot be expected that the powers-that-be who consider the police an essential part of their power will let the power go. That is the crux of the problem of our law enforcement agencies working for the ruler rather than the ruled. On 22 September 2006, the Supreme Court Bench of Justice YK Sabharwal, Justice CK Thakker and Justice PK Balasubramanyam gave the historic judgment, ordering states to implement seven programmes in response to a petition filed by former IPS officer Prakash Singh. The apex court urged the states to come back to it with a compliance report within three months of the issuance of the order. Due to certain glitches pointed out by the states, the court let implementation of four provisions be delayed while the other three had to be implemented forthwith. (More about these seven steps later)

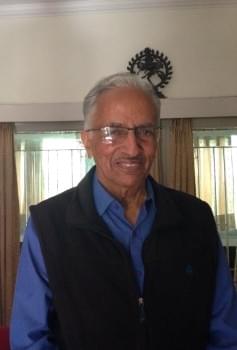

Singh agrees with the contention. “That is true. That is the main reason why it has not been possible to implement police reforms,” he said in an exclusive interview to Swarajya.

In this country, the strongest of formations are the political class and the bureaucracy. They are the strongest organized units in this country. And when they combine, you can take it from me that nothing in this country will move. If they join hands and decide ‘this has to be done’, there’s no stopping them, and if they decide ‘that cannot be done’, it’s bound to falter and fail. Leave aside the police, this formation has been able to humiliate the Indian Army, which is (otherwise) such a respected and strong body. Even the Army had to eat a humble pie on so many occasions; chiefs are humiliated on so many issues because of opposition (to their proposals) from the bureaucracy.

Police is completely under the control of the political class and the bureaucracy. They have wielded this power so long that it has had an intoxicating effect on them. Having become addicted to using the police, for certain purposes over and above its normal functions—for example, to frame somebody, to ensure their supporters do not get caught by the police, are not charge-sheeted, etc—they are not letting this power go out of their hands.

So, are we destined to be governed by the archaic and colonial police laws dating back to 1861? Along with Singh, another Director General of Police NK Singh had filed a PIL in the Supreme Court in 1996 to instruct all governments, both central and state, to address the issue of obsolete and dysfunctional policing in the country by implementing the recommendations of the National Police Commission. The committee then formed by the Union government under instructions of the highest court, under the leadership of JF Ribeiro, a former chief of Mumbai and Punjab police, spent all of 1998 and ’99 to produce two reports. Then Home Secretary K Padmanabhaiah came up with another set of recommendations in 2000. In 2003, there was yet another committee on reforms of the criminal justice system headed by retired Chief Justice of Kerala and Karnataka VS Malimath. Two years thereafter, the Soli Sorabjee report proposed a Model Police Act.

Speaking at the round-table conference on “Smart Policing – India’s Growth Imperative” organised by FICCI in the national capital this year in July, Ribeiro said,

The technology and all other advancement cannot be functional if the political class keeps interfering in the works of police. It is very sorrowful.

A year after the Supreme Court agreed with Prakash Singh’s arguments, 70 odd activists, police and government representatives under the aegis of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative had come together at a national workshop in Delhi to campaign for better policing. Several other citizens’ initiatives to make the police change in the last 40 years—and state governments’ commissions examining the problems of the police in the 1960s, the Government of India’s Committee on Police Training in 1971 and later the National Police Commission in 1977—have yielded only marginal steps in the direction of reforms.

The 1902 Sir AHL Fraser Commission constituted by the British Raj refused to acknowledge that the 1861 Police Act was the root cause of ineffective policing. Since the law was made in the aftermath of the 1857 struggle for independence, it naturally designed a force that would serve the ruler and look at the subjects perennially with suspicion as subversive elements. The attitude of the average policeman of today continues to be as colonial. The governments run wholly by Indians accepted that the 19th century statute was an issue, but were reluctant to change it as it couldn’t think of letting go of its unbridled powers.

Perhaps it was the easiest to reform the police when India was newly independent. Besides freedom from a foreign power, there was an immediate provocation. Days before the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, AG Noorani informed through an article last year, Jamshid Nagarvalla of the Bombay CID had sought the permission of Bombay’s then Home Minister Morarji Desai to arrest VD Savarkar on the basis of the assailant Madanlal Pahwa’s visit to him the week before. Desai refused. Though Savarkar was completely exonerated by the court during the trial of the conspirators of the Gandhi assassination, some like Noorani continue to believe that the arrest could have possibly averted Gandhiji’s murder.

A Commissariat for Kanpur is a more recent case in point. It was announced almost 40 years ago. Vasudev Panjani was tipped to be the commissioner holding that post. He along with the then Home Secretary of Uttar Pradesh Kalyan Kumar Bakshi toured the country to study the commissariats wherever they existed.

When they came back with Panjani designated to take over the charge of the Commissioner of Kanpur, the bureaucrats involved in the process played spoilsport. Their peers played the devil elsewhere and now a commissariat is nowhere to be seen in north India except in Delhi. Panjani today leads a dejected retired life in Dehra Dun.

“The bureaucracy scuttles any proposal which is otherwise committed by the political establishment,” Singh said. He finds the bureaucracy the bigger problem. He says that even when the political leadership agrees to certain definitive proposals, when the issue is taken to the respective secretariats of the states, the babus come up with all kinds of objections.

And sometimes one is witness to the farce of a political party asking its own government to execute reforms while the government does nothing about it! Two months ago, TRS MP from Karimnagar B Vinod Kumar had urged the state government to initiate reforms in the state police. In a letter to Telangana home minister N Narasimha Reddy, he wrote,

As you are aware, there is a strong need to reform the police in our country. Across the nation, including in our own state, they face allegations of corruption, inefficiency and citizen harassment.

Pointing out that no state had moved in this direction, Kumar said the new state of Telangana could create history if it implemented the directives. Are we supposed to be impressed by this intra-party communiqué?

Back in Uttar Pradesh, the proposal for a commissariat in Kanpur was significant because a commissariat witnesses little political and bureaucratic interference, and is recognised as the most effective policing system across the world. In its absence, the orders have to be taken from the district magistrate, with whom the superintendent of police may or may not agree. On critical occasions, it becomes a nightmarish experience for the policemen managing a city or township to locate the DM and seek his approval for necessary action. Then there is the local legislator who would induce politics into policing, asking the police to go soft on a set of unlawful persons while being harsh on others.

A commissariat exists in most south Indian states [In 1977, then Prime Minister Desai had wondered why the system couldn’t be incorporated in India that lies to the north of the Vindhyas]. That partly explains why law and order in that region is not conspicuous by its absence as it is in many north Indian states. Delhi has it, too; besides, the hands of the Union Home Ministry to which Delhi Police reports are so full that it cannot spare time to interfere in the capital’s daily policing activities. Of course, Delhi Police is also blessed with no crunch in resources. A citizen who lives in the National Capital Region can feel the difference while living in or travelling between, say, Gurgaon or Faridabad and NOIDA via Delhi. If there is a street-side brawl in Delhi, a PCR arrives in no time; if, God forbid, you are looted in Uttar Pradesh, the police, before taking action, would ascertain whether the criminal is a protégé of a local political honcho. If he is, forget police action.

It is possible that the autonomy Delhi Police enjoys breeds a little corruption and police autocracy, but in the overall cost-benefit analysis, the benefits far outweigh the costs, Singh believes. Nobody breathes down the neck of an officer and there is no political diktat on postings of SHOs in Delhi. In almost all other states, the MLA insists that the local thanedar must be of his or her choice. In some districts the situation is so bad, the SHO virtually posted by the MLA pays a hafta to the politician to keep him posted there so that he can keep extracting unscrupulous personal benefits from the area under him.

It is common knowledge in Uttar Pradesh that, to celebrate the birthday bash of former Chief Minister Mayawati, money was collected even from policemen down to the level of thanas (police stations) and chowkis (temporary or movable police posts). The Samajwadi Party is alleged to misuse the police in a different way. While residents of western parts of Uttar Pradesh allege that no Muslim hoodlum can be arrested unless the police receive a green signal from Azam Khan, during the infamous Badaun rape investigations, media was amazed to note that every policeman concerned with the case was a Yadav—a community, the Dalits who bore the brunt of the atrocity, don’t trust.

Policemen by and large have unfortunately come to terms with this reality. Officers now identify themselves with one of the two political groupings in all electorally bipolar states. As an IPS officer is transferred immediately after a new party takes to power, he is so resigned to fate that he does not complain.

On 5 September, in a meeting convened at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) to create new institutions, of which this writer was a part, Prakash Singh was visibly peeved at the Narendra Modi government doing nothing to change policing in the country. However, during the exclusive interview in November, he said the BJP had a better record than other parties in matters of corruption. He did add though that the political character across the parties is the same. His missives to the Modi government bore no fruit. The silver lining in the cloud came in the form of the Prime Minister’s address at the All India Police Congress in Guwahati where he stressed the need for SMART police, wherein the acronym stood for Sensitive, Mobile, Accountable, Responsive and Tech-Savvy. But speeches are not enough. Police under the present system, where they are not accountable to the people, cannot be sensitive.

Singh told Swarajya that he had met with the then chief ministers of Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra after the court order.

When they meet they are very polite; they are courteous, too; they say, ‘Yes, we will look into it,’ or ‘aap jo kaghaz laaye hain, de deejiye hamein; ham us pe karyavahi karenge’ (give us the papers you have brought; we will take action on it). A vague kind of assurance is always given, but beyond that nothing happens.

For example, in March this year, a day after the Devendra Fadnavis government had brought in an ordinance to change the Police Reforms Act, several activists rubbished the move as an eyewash. The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), the collected materials of which are a great reference material for all concerned with police reforms, was upset. Activist Saurav Datta of the said NGO was of the opinion that the entire legislation was flawed and no “piecemeal” changes could turn the Maharashtra Police into a pro-people force, given that the state has had a long, dubious record of politically inspired postings and transfers. Dolphy D’Souza of the Police Reforms Watch found the ordinance a “patchwork”. The activists demand a complete replacement of the “flawed” Maharashtra Police (Amendment and Continuance) Act, 2014. Ironically, Chief Minister Fadnavis used to take these activists along in his campaign against the Congress government’s “excessive and unjustified” control over the police as the then opposition leader, and now he finds no time to spare for them.

Prakash Singh had to deal with political interference as DIG – Meerut, DIG – Assam and DGP – UP. While he said that it was up to an officer how much interference he would live with, his own refusal to bend before the political executive led to his ouster from all these places. So, after his retirement, he took the matter to court in public interest.

But, out of all the reform measures the Supreme Court advised the governments to carry out, what they have given us is a diluted version of a few and plain refusal to execute the rest. The court had ordered the governments to take these seven steps:

- Formation of state security commissions,

- Making a transparent selection procedure and assuring a minimum tenure of the DGPs of states,

- Assuring a minimum tenure of IGs of zones and ranges and all officers down to the rank of SP of a district, a circle officer of the subdivision and an SHO,

- Separating investigation from the routine law-and-order mechanism,

- Forming a police establishment board,

- Constituting a police complaints authority, and

- Forming a national security commission.

Besides, Lok Satta Party founder N Jaya Prakash Narayana has proposed recruiting only persons of officer cadre to the investigation wing, increasing the strength of police by 50 per cent, setting up an independent prosecution wing and local courts for every 50,000 population, which Telangana Director General of Police Anurag Sharma accepts as necessary.

“The states are averse to having state security commissions,” Singh informed. Besides, ensuring a minimum tenure for DGPs, IGs and other officers—under normal conditions and not in case they are found to be corrupt—and setting up a police complaints authority are the sticking points. The Supreme Court listed some exceptions to the minimum tenure order to ensure no posting turns into the assured officer’s fiefdom.

A state like Bihar made the exceptions more overarching, thus reducing the reforms to a travesty. The first state to pass a new Police Act in 2007, Bihar under Chief Minister Nitish Kumar diluted the SC directions by appointing only government members in its SSC. A DGP could be removed before his completion of the assured two years on “administrative grounds” or “any other reason”. The Police Establishment Board (PEB) of Bihar can only transfer low-ranking officers; it cannot reject appeals on illegal orders by the state government.

The situation is as bad in Goa where the PEB’s powers are restricted to transfers below the rank of deputy superintendent. In Karnataka, while a new Act by BS Yeddyurappa’s BJP government had brought all transfers above the rank of additional superintendent of police including those of IPS officers under the purview of the PEB, Siddaramaiah’s Congress government pushed through an amendment in 2013 to give the political establishment fresh control over the state PEB.

That does not mean, however, that Yeddyurappa was all clean on this count. Before demitting office, his dispensation pressured the PEB to transfer several IPS officers. About half-a-dozen legal cases are running against the board and the state government in courts as a result. In one such case, Bangalore’s then rural deputy superintendent Shankarappa is accused to have ordered closure of his office to avoid another officer taking charge!

Separating the investigation arm of the police from its regular maintenance of law and order job should be the easiest for the provincial governments. A bench of Justice TS Thakur, Justice RK Agrawal and Justice Adarsh Kumar Goel rightly said last year that this was where reforms could begin in earnest. Calling the judiciary a stakeholder in the process of police reforms, the judges expressed concern at the fact that shoddy investigations often led to a weak prosecution, due to which the court has no option but to let the accused go scot-free.

One recalls the Badaun case where the CBI concluded there was no rape, or the 2008 murder of Aarushi Talwar in which the people still cannot make out whether the CBI version or that of the victim’s parents is correct. Though this central investigating agency is better equipped than the state polices, more often than not, by the time it receives a case, the evidence has been tampered with or even eliminated and the witnesses have been browbeaten to silence. At times, the state police are suspected to have connived with the criminals to deliberately botch the case up before it is forced to hand over the files to the CBI.

The process of separation should begin in the metropolitan cities where the population is in tune of 10 lakh or more and, based on the experience, the model can be replicated in the smaller policing districts. The metros should be the priority because that is where law and order is a constant issue. Policemen busy in bandobast cannot spare the time required for investigations into individual cases. So, several states moved in this direction without any fundamental objection to the directive except for the refrain that they did not have adequate manpower—and the finances needed for the purpose—for the requisite separation. That’s a ruse; “They just don’t want to invest in the police,” according to Singh.

The fact that funds are not a constraint is seen in the reality of our terror-fighting apparatus. Weeks after the 26/11 attacks on Mumbai, the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & Systems (CCTNS) was formed for coordinated database sharing between 14,000 odd police stations across the country. Seven years later, the network is not ready despite a total budget of thousands of crores of rupees including Rs 800 crore spent on the CCTNS. Government proposals, committee recommendations, police reports, red tape and inter-departmental territorial fights have together put in place a mess in the name of an integrated security system.

Now, if the police do not have adequate manpower for separation of departments, how can it have enough to provide security to every individual who wishes to express his opinion freely? That tolerance and freedom of expression are terms being used politically these days is a different story altogether.

We have the Ford Foundation’s Abhijit Banerjee complaining through an article in Hindustan Times that “our democratic culture does not prioritise protecting an individual’s right to live life her way, especially if that is not our way or the way of the community.” He talks of bans on books, films, works of art etc. Singh finds this a cavil. He believes that the society has its own rights, too, and these cannot be violated to offer incontestable freedom of speech to individuals. He mentions incidents like a politician (Akbaruddin Owaisi) saying he could teach the Hindus a lesson if the police were to stand at bay for 15 minutes and another (Lalu Prasad Yadav) calling the Prime Minister a narbhakshi (cannibal). The former IPS officer would like to tell the protesting intellectuals that these politicos are still hale and hearty, and questions how anybody could say there was no freedom of expression in the country.

A state security commission is the main provision the Supreme Court visualized to stop interference in policing. This is supposed to be a watchdog between the government and the police. It would ensure on the one hand that the government wouldn’t interfere in policing while, on the other, the police wouldn’t transgress law. For that, a balance in the composition of this commission—between government and non-government representatives—was an imperative. The second set of people had to be such who inspired public confidence with their record of personal integrity. It so transpired that the commissions were constituted, but “there was a preponderance of government representatives” and those picked from the civil society were ill-famed as “chamchas” (stooges) of the government, whether they were retired judges or retired police officers, Singh said.

In states that observe bipolar electoral contests, when the opposition comes to power, it does to the unseated party what the latter had done unto it during the previous regime: witch-hunt. When the party at the receiving end regains power, it seeks revenge. A typical case is that of West Bengal where for 34 years the Congress and then the Trinamool Congress complained of no progress in the cases of political murders. Now the Trinamool Congress is using the state police with as much impunity as the CPI(M) did during its tenure. Watching regional television channels, one comes to know that the allegation of witch hunt is as commonplace in Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. DMK and AIADMK in the first and SP and BSP in the second state take turns to be the perpetrator and the aggrieved party. This vicious cycle could end if the state security commission were to become a reality.

It is surprising that the Supreme Court, which variously betrays sensitivity about its supremacy, does not issue a Contempt of Court notice against the states for non-compliance of its 2006 order. The petitioners have approached the apex court at least twice—only to see that the court let the state secretaries go with just a “tongue lashing”. The babus returned from the court happy that they could take the judges for a ride by citing procedural hassles.

In July 2013, for instance, after the secretaries got away with their cop-outs, director of the CHRI Maja Daruwala said,

The fact that the court has reason to summon chief secretaries to hear why its orders have not been obeyed indicates the deep resistance governments in loosening their complete control over how policing is done. The court’s orders condition the relationship of police and political executive, and will help reduce undue political interference. It will also create more professional, less biased policing.

The police complaints authority was turned down by most of the states with the excuse that it would lead to a multiplicity of authorities. The bureaucracy cited departmental institutions, the magistracy, state human rights commissions and women’s commissions, Scheduled Caste commissions etc as adequate mechanisms for redress. Ergo, some states constituted the body with diluted provisions; others flatly refused to have the body in the first place.

At the state level, a retired Supreme Court or High Court judge was supposed to head it; at the district level, a retired District & Sessions Court judge had to lead the authority. In Gujarat, it is but headed by an IAS officer who is not sure where his jurisdiction ends and that of the Lokayukta begins. Andhra Pradesh, while hastily setting up its security commission, the Police Establishment Board and ensuring the selection and tenure arrangements for the DGP, violated the court’s order in the implementation of each provision—the apex court found in 2013.

Apart from these two states, Punjab, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh had actually filed review petitions, rattled by the 2006 order of the Supreme Court. These petitions were dismissed by the Supreme Court on 23 August 2007.

The apex court had advised the formation of a complaints authority to look into the charges of grave misconduct, which the bodies cited as adequate by the bureaucracy are too supine to act upon. This is not a complaint of such officers alone who are dying for reforms; as an activist, I have taken victims of police abuse to the women’s commissions of Haryana and Uttar Pradesh and found that their “duty” ended with issuance of querulous letters to the police. On one occasion where a distressed woman had moved from Gurgaon to Delhi for reprieve, but received none, then chairperson of the NCW Mamta Sharma—who was otherwise very attentive while we presented our case—told me her powers entailed no more than reprimanding the policemen concerned. Mercifully, as indicated above, the Delhi Police took the misbehaving cops of the thana concerned to task soon. Haryana Police had taken no action against the police officials who had made light of a case of molestation in front of a mall in Gurgaon on the 2012 New Year’s eve, after they cast aspersions on the character of the victim. Worse, a certain section of the civil society proved as callous, calling me over the phone and seeking an explanation as to why I was after the erring policemen’s jobs!

The insensitivity on the part of the authorities is also a result of a tacit understanding between the wings of the government to not make life difficult for each other. And then there is casteism! Certain sections of the population are to be treated with kid gloves for the sake of political correctness.

Singh agrees that the colonial hangover and the further fault lines that a regressive society added to policing have gone on for so long that now many officers and citizens alike look at cases of misconduct by law enforcers as “business as usual”.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court had factored in the issue of multiplicity of authority and noted that a matter need not be taken to the police complaints authority if another state-level authority was already seized of the matter. Thus, there is no room left for the states to deny citizens the much-needed reforms.

Mind you, Singh does not approve of activism by serving policemen. On my giving him the example of Amitabh Thakur, who famously invited Mulayam Singh Yadav’s ire this year, he said activism was not bad but it could be practiced only after the years in service or after voluntary retirement from the job, until which time the code of conduct for the men in uniform must be respected.