Economy

Modi’s DBT Review 3: Dear Mr Modi, Some Things You Need To Do To Salvage The Programme

Seetha

Oct 04, 2016, 12:09 PM | Updated 12:09 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

- It is clear that the Chandigarh Administration went into the pilot without adequate preparation

- An important part of the political management of a cash-instead-of-food programme is to politically de-risk the beneficiary

As the second part of this series showed , the teething troubles that the rollout of the cash transfer pilot in Chandigarh are facing is leading to nostalgia for the old public distribution system (PDS), even though beneficiaries admit that it was far from perfect. The many critics and opponents of cash transfers have been prompt to exploit these flaws, convincing affected people that the idea itself is problematic. The harried beneficiaries, who do not have the bandwidth to run around getting grievances redressed, are readily convinced.

Is this the result of a concept problem, a design flaw or just lackadaisical implementation? “The conceptual case for going to cash is very clear, but a lot of attention needs to be paid to implementation detail” says Karthik Muralidharan professor at the University of California San Diego, who has been involved in cash transfers experiments for several years.

Muralidharan flags two issues that need to be addressed in any cash transfer in lieu of PDS programme (he refuses to speak specifically about Chandigarh). One, before the policy change, there should be a political economy analysis of vested interests who could be affected and how they are to be neutralised. Two, the focus should be more on keeping the beneficiary experience as painless as possible rather than fiscal savings.

So, where did the government go wrong and what does it need to do?

It is clear that the Chandigarh Administration went into the pilot without adequate preparation, though it denies it. Hence, the problem of people getting left out because of bank accounts not being seeded with Aadhaar and the technical and administrative glitches that result in people not getting cash. It may have been worth the while for the rollout of the programme to have been delayed till the Administration ensured that all the identified beneficiaries had Aadhaar-linked bank accounts. The Chandigarh pilot may then have had a smoother ride and not generated resentment.

When problems do arise, effective grievance redressal mechanisms have to be available. Two successful cash transfer in lieu of food experiments have been managed by SEWA-Bharat, a civil society organisation. In both these cases, there was a lot of hand-holding by the activists. In Chandigarh, the grievance redressal mechanisms are there, but need to be toned up.

Two, implementing a programme with huge political consequences as a purely bureaucratic exercise is an unwise move. What appears to be missing in Chandigarh is political and perception management; the programme is seen as being driven by remote and faceless bureaucrats from Delhi.

The SEWA-Bharat pilots in Delhi and Indore were successful because the organisation took care to explain to people what they were signing up for and what it involved. The beneficiaries in Chandigarh are clueless about the logic behind cash transfers, how the Rs 95 per person figure has been worked out, how this is the same as the benefit reaching them earlier, except that the government is now actually putting in their hands the cost it used to bear.

This perception management cannot be done by the bureaucracy, which should focus on processes. Chandigarh did use the National Service Scheme to do a survey-cum-awareness building exercise, but student-volunteers do not have the same resonance with the people that civil society activists and grassroots political workers.

True, many civil society activists are ideologically opposed to cash transfers and cannot be used to explain its benefits. There could also be a problem in using party cadres. They are controlled by local leaders who are often in league with ration shop owners (the section that stands to lose out the most because of cash transfers). In Chandigarh, the chairman of the Govt Fair Price Shop Welfare Association is also the vice-president of the Chandigarh unit of the BJP and the president is a local Congress leader!

So, it is important for the central leadership of a political party to send out a clear message. The BJP aggressively marketed the Jan Dhan Yojana and Mudra schemes; why cannot it do the same with the cash transfers pilots? This will send out a message to local leaders as well. It may not always work. The Congress tried to involve local leaders and cadres when it rolled out a direct benefit transfer scheme in food, the Annapurna scheme, in 2012; but many of these leaders were unhappy with then chief minister Shiela Dikshit and so did not work to make the programme a success; it got discontinued when the NFSA was enacted. But it is worth a try.

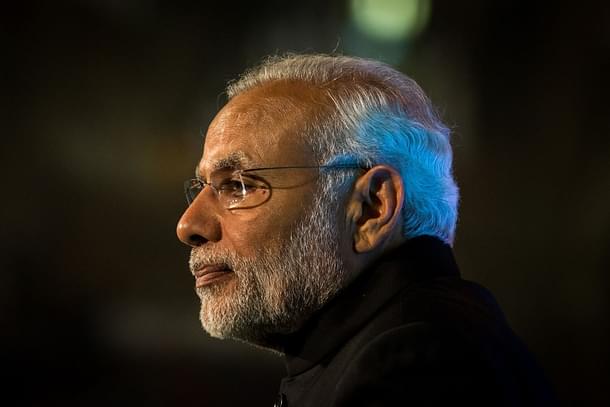

Politically sensitive programmes need a party big gun to market them. In Delhi, chief minister Arvind Kejriwal often takes to FM radio to explain new initiatives, especially when they could generate resistance. After the floods in Chennai, residents of affected areas got phone calls with a recorded message from chief minister J Jayalalithaa assuring them that the government would reach compensation to them. Though the cash transfers programme is known as a pet scheme of the Prime Minister, it does not have his branding. Could the government not have somehow used Narendra Modi to sell the idea? Could other ministers (Ram Vilas Paswan, food and public distribution minister or finance minister Jayant Sinha) not have been deployed in some way? At least in Chandigarh, both these leaders could have struck a chord with the migrant labour population from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

A clear signal should also go out to all levels of the bureaucracy – that this is an important programme and that any dawdling or active sabotage will not be tolerated. Such a message went out from no less than the chief minister in the case of flood relief in Chennai. Bureaucrats facilitating the programme should be supported; those erecting roadblocks should be face the rap (except if they are raising genuine concerns).

Muralidharan points out that implementation hassles could often be the result of deliberate sabotage by those who lose out. “There are enough powerful intermediaries who would fight back,” he notes.

J-PAL did a proof of concept study on cash transfers in lieu of PDS in Patna in 2012 and its report highlighted the problem of pushback from local power-brokers, including ration shop owners who actively discouraged people from exercising choice (people could choose between cash and PDS grains).

Indeed, ration shop owners are closer to the beneficiaries than even the lowest level food inspector is and have enormous potential to influence opinions. In Chandigarh, too, the ration shop owners are often the first point of contact when beneficiaries face problems and are quick to add fuel to the resentment fire. There are complaints of open market prices rising after the launch of the programme and, if true, then this could be deliberate.

Perhaps the biggest mistake made in Chandigarh was to completely shut down all the 93 ration shops. The only sop they got was licences to sell 5 kg LPG cylinders. This was hardly sufficient to make up for the loss in business. The angry backlash was inevitable.

Last year, the Rajasthan government started branding ration shops as Annapurna Bhandars in collaboration with Future Retail, allowing them to stock select non-PDS items and thus increase footfalls. One of the four objectives of this initiative was to act as a sweetener to get ration shop owners to shift to biometric POS machines which will curb diversion – what they would have lost in earnings from pilferages would hopefully be made up with the extra business. The buy-in to Annapurna Bhandars is still slow, but it does attempt to address the resistance problem.

An important part of the political management of a cash-instead-of-food programme, says Muralidharan, is to politically de-risk the beneficiary. “It is necessary to think about a transition path that protects the poor.”

This is best done by giving people choice – let cash transfers work along with PDS to see which works better. In Chandigarh, the shutting down of all ration shops was a huge mistake - people had no alternative when their transfers did not come through and the government came across as callous. Renana Jhabvala of SEWA-Bharat points out that the one-year pilot programme it conducted in Delhi showed that errant ration shop owners started falling in line when they realised people were preferring to buy from the open market. Perhaps, the Chandigarh Administration has realised this and has now re-issued licences of 45 ration shops.

Six months is not enough to pronounce a cash-in-lieu-of-food programme either a resounding success or an abysmal failure. It is, however, time to fix the problems dogging it. If Narendra Modi wants to make his mark in the field of subsidy reform, he has to pay attention to this.

Seetha is a senior journalist and author