Politics

A Historical Survey Of The Left In Indian Politics

Shrikanth Krishnamachary

Jun 10, 2019, 10:02 AM | Updated 10:01 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The 2019 Indian general election has been acknowledged as a watershed already. It marks the first time since 1962 that the incumbent Prime minister has led his party to an absolute majority after a full five year term in office. It also marks the establishment of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as a pan-Indian force, with impressive number of seats and votes in states like Karnataka and West Bengal (WB).

However one aspect of the 2019 elections has gone largely under-discussed. It marks the death-knell of the Left in India as a major political force.

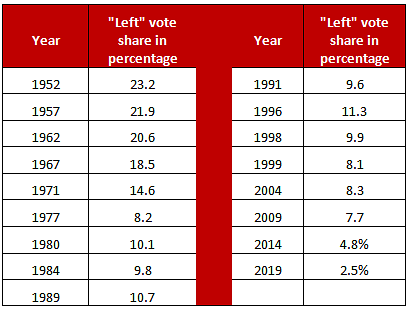

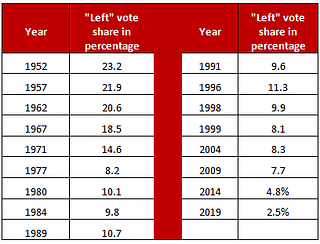

The share of the Left vote which was at 23 per cent in 1952 has been reduced to under 2.5 per cent in 2019! It’s the near terminal decline of an important strand in Indian political life, whose roots go back to over 150 years.

This might be a good occasion to reflect on the history of Left-wing politics in India — reflect on its incipience, its growth, its many electoral achievements, and the reasons for its stunted development and its imminent demise.

Defining the “Left”

Before we get started on this survey, it is worthwhile to clarify a few things. What do we mean by the “Left”? By "Left" I am referring not merely to the two Communist parties, but the socialist parties of various hues that have influenced India over the past 100 years. Parties, to varying degrees, committed to the ideal of a class struggle and social ownership of the means of production.

So, the label encompasses the following parties:

- Communist Party of India

- Communist Party of India –Marxist

- Communist Party of India - Marxist-Leninist

- Revolutionary Socialist Party

- Forward Bloc

- Socialist Party

- Praja Socialist Party

- Samyukta Socialist Party, among others

The label does not include the Congress, of course. It may be a center-left party but not quite "socialist". Nor does it encompass caste-based outfits and regional parties, which may toe a socialist line, but don't quite fit the classical definition of the "Left". For example, Janata Dal and its offshoots, Samajwadi Party, Rashtriya Janata Dal, Bahujan Samaj Party, etc.

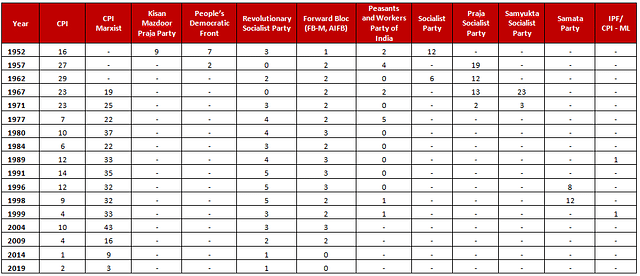

Now, let’s examine some numbers to illustrate why 2019 marks a momentous event in the electoral history of the “Left” in India. Here’s a look at the seat tally of “Left-wing” parties (as defined above) in our Parliament from 1952 to 2019 [Table 1].

The "Left" parties won 50 seats in the first Lok Sabha, reached a high of 82 seats in 1967, and have been reduced to single digits now in 2019.

In 1952, the “Left” was represented in the Lok Sabha by not just the Communist Party, but several other socialist parties - parties that have gone into the pages of history and which we barely recall today.

- Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party of Acharya Kripalani

- Socialist Party of Jayaprakash Narayan

- People’s Democratic Front - an offshoot of the Communist party with a regional base in Telengana.

Let’s examine how the seats were distributed across the Left Parties in every general election since 1952 [Table 2]. Notice the wide prevalence of socialist outfits in the early decades and the shrinking of the “Left” to mean just the two communist parties in our time.

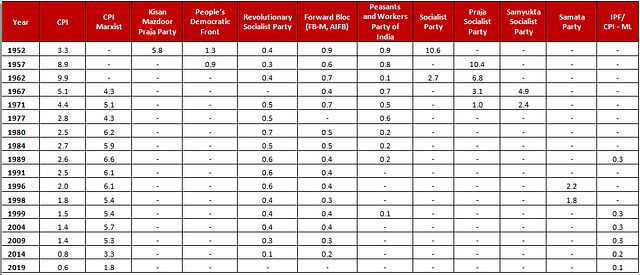

In terms of vote share, the decline is even starker In 1952, 23 per cent of the electorate voted for the parties identified as belonging to the “Left”. This remained stable at around 10-15 per cent for much of Indian history before going into a free-fall in the past decade.

And here’s how the vote shares have been distributed across parties since 1952.

Back in 1952, the leading party in terms of vote share was not CPI but the Socialist Party, which accounted for 11 per cent of the vote, while CPI was at just over 3 per cent. So the numbers clearly suggest that we are now at the end of a long tradition in India politics.

We must use this opportunity to reflect on history a bit and ask some difficult questions.

- Why did the “Left” never take off in India?

- Why is Socialism in the classic sense unpopular in India despite India being a poor country?

- Did the left-wing character of the Congress post 1960s rid the Socialists and Communists of talking points?

- Did the Indian institution of Caste come in the way of creating effective narratives around Class struggle?

These are questions worth asking.

Origins of the Indian “Left”

The origins of the “Left” as a strand in Indian polity go very far back in time. It even predates the Russian Revolution. Some of the early key figures were in Bengal - a region where the Left has remained formidable for the longest period of time, along with Kerala.

One early figure is a man named Shashipada Banerji - 1840 to 1924, a Brahmo Samaj leader and social reformer. The “Working Men’s Club” that he founded in 1870 is viewed as one of the very first labour organizations in India. He was also the founder of a journal named “Bharat Sramajibi” - which enjoyed a circulation in excess of 15,000 at its peak.

But Banerji may not be regarded as a ‘socialist’, let alone a ‘communist’, in a modern sense. He was more akin to a philanthropist. A well-wisher of the working class. Hardly an advocate of class struggle.

But socialist ideas were very much in currency in Bengal at the time. Even a nationalist figure like Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (who we don’t even remotely associate with the “Left” today), was influenced by socialism.

Here’s what he wrote in his essay collection - “Samya” (Equality) in 1879.

The great tree which Rousseau had planted,through his theory that ‘the land belongs to the common people’ bore ever newer fruits. Europe is full of the fruits of that theory till date. ‘Communism’ is a fruit of that tree. The ‘International’ is a fruit of that tree

It was in 1912, that Karl Marx first found explicit mention in Indian literature. In a write-up titled, “Karl Marx - a Modern Rishi” by one Lala Hardayal in the Modern Review, a Calcutta journal. Two years later the first biography of Marx featured in the Malayalam language - by one Ramakrishna Pillai.

But it was with the Russian Revolution of 1917 that the socialist wave in Indian thought really took off. Many strands in Indian political life were greatly influenced by it.

The Ghadar Party, comprising of expatriate revolutionaries in Canada and Punjab, were influenced by Bolshevik ideals. Lala Hardayal, whom we have alluded to, was an influential Ghadar leader. Elsewhere in Punjab, young men like even Bhagat Singh were very much taken in by Socialism. So the penetration of these ideas wasn’t just coffee table talk. It was fairly deep.

Founding of the Communist Party of India and the Congress Socialist Party

In 1920, the Communist Party of India (CPI) was founded, curiously enough, in Tashkent! One of its co-founders was Manabendra Roy (better known MN Roy) - an interesting man, who founded the Communist Party of Mexico, even before he was involved in founding CPI.

Interestingly Roy got disillusioned with Communism in his later years, and abandoned the Communist Party post World War II.

Meanwhile the Congress party itself was also impacted by the leher of Socialist ideas. There was a socialist caucus within the Congress - the Congress Socialist Party (CSP) which was founded in 1934. Its leaders included the very young Jayaprakash Narayan, Ram Manohar Lohia as well as Minoo Masani! Men who would play key roles in post-independence Indian politics.

Interestingly Minoo Masani, a co-founder of CSP, moved completely away from Socialism to the other side post-independence. He embraced free market economics, and became a collaborator of Rajaji and a stellar leader of the conservative, right-wing Swatantra Party.

So the key point to note here is that some of the progenitors of Communism and Socialism in India (men like MN Roy and Minoo Masani) underwent major conversions of sorts (especially Masani) later in life. However, the intellectual and political traditions they kick-started remained a fixture in Indian life for many decades. Until now, that is.

Subhas Bose founded another left-wing party, the Forward Bloc in 1939, after being pushed out of the Congress by Gandhi and the more politically conservative Congress leaders. The Forward Bloc remained a political party long after Bose’s passing, and in fact has won seats in just about every Lok Sabha from 1952 till 2014 with one or two exceptions.

Meanwhile the CPI (founded in 1920), obtained a foothold in Kerala in 1937, when several influential members of the CSP (Congress Socialist Party) became CPI members.

Among them was EMS Namboodiripad. There was considerable co-operation between socialists and communists in that period. EMS Namboodiripad for instance was both a CPI member and a general secretary of CSP.

But throughout this period, the CPI remained an illegal entity. It was only in 1942 that it was legalized by the British Government, in part because of the War effort, and the British alliance with Soviet Union against Nazi Germany.

Post-independence successes

In the years immediately following Independence, Communist party leaders were involved in several local rebellions against monarchs and feudal lords. Most notably in Telengana. Puchalapalli Sundarayya is an example of a prominent CPI leader who was involved in the violent peasant revolts and guerrilla warfare in Hyderabad state.

In fact, the People’s Democratic Front that won 7 seats in the first Lok Sabha (1952) was an offshoot of the CPI, and centered around Telangana - comprising mostly of leaders who had led the revolts few years previously.

In the 1952 elections, we have already seen how impressive the performance of the Left was. The Socialist Party (comprising of JP among other leaders) got the most votes (11 per cent vote share) but in terms of seats the CPI was the leader with 16 seats despite just 3 per cent of the votes. Interestingly most of CPI’s seats were from Madras (now Chennai), and not Travancore-Cochin. In the state elections of Travancore-Cochin in 1952, CPI was banned. But it was just a matter of time before this was reversed, for five years later in 1957, history was made.

The CPI defeated the Congress and stormed to power to form the government in Kerala. The first time anywhere in the world that a Communist party had been democratically elected to power (barring San Marino). EMS Namboodiripad was the chief minister.

Split among Communists

In 1964, the CPI split into two — the CPI and CPI (Marxist) — both parties are with us to this day. The basis for the split appears to have been around political strategy. While CPI favored greater collaboration with the Congress, CPI (M) sought greater distance and greater ideological purity.

Today, CPI(M) remains much more dominant than CPI, both in West Bengal and Kerala.

Interestingly enough this ideological division between the two parties persisted even as late as the 1990s - when in 1996, CPI was open to joining the United Front led by Deve Gowda, whereas, the CPI (M) chose to stay more aloof, and provide outside support.

The decline of the non-Communist Left

Back in the 1950s, the Socialists were no less strong in Indian polity than the Communists. The Socialist party won 11 per cent of the votes in 1952, as already alluded to. Besides that there was also the Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party, founded by Acharya Kripalani. The KMPP won 6 per cent of the votes in 1952. So these two socialist parties between them won 17 per cent! In the late 50s, they merged to form the Praja Socialist Party — a party that won over 10 per cent of the votes in 1957.

But in the ‘60s, Socialism weakened, while the Communist party vote shares continued to stay healthy. The Praja Socialist party split, with a breakaway faction called Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP) that was influential in the ‘60s-‘70s.

The Lohia supporters were associated with SSP, and so was George Fernandez, who in later years, would serve in conservative governments like that headed by Vajpayee! And as a Defense Minister to boot!

The fate of Socialist and Communist parties was very starkly different in the decades between ‘70s and ‘90s. While the two Communist parties remained strong in their two regional bases — Kerala and West Bengal, the Socialist parties declined terminally, thanks to the Emergency.

The rise of caste-based parties in Northern India

The formation of the Janata Party — an amalgamation of all anti-Indira forces in 1977 — meant that many parties on both the Left and the Right lost their identity post-merger, be it the Swatantra Party on the Right, or parties like Praja Socialist party and Samyukta Socialist party on the Left. By staying aloof from the JP movement, the Communist parties maintained their distinct identity to live another day, whereas Socialism died as a political force.

In the ‘80s/’90s , as Janata Party broke up, the various shrapnel thrown up by that implosion transformed into the different caste-based parties of North India — be it Janata Dal in Bihar, or the Samajwadi Party in UP. While these parties called themselves “socialist” (Samajwadi), they were not left-wing in a classical sense. Their embrace of caste and identity meant that they were a far cry from the left-wing ideal espoused by JP, Lohia or Fernandez.

Fernandez in fact was an honorable exception, in terms of staying away from identity politics and forming the Samata Party in 1994, along with Nitish Kumar — which can be regarded as the last “socialist” party of India. But Samata too eventually bit the dust when it merged with the Janata Dal (United), and became a regional Bihar force.

The Communist parties on the other hand, remained regional forces, strong in West Bengal (WB) and Kerala but non-entities elsewhere. In fact, the CPM ruled WB from 1977 till 2011. But the decline of CPM in Bengal started in the new millennium with the emergence of a regional Bengali power — the Mamta-led Trinamool, a party that broke away from the Congress.

Diagnosing the causes for the Left’s decline

So clearly, the decline of the Left in India can be attributed to two reasons: –

- Caste - the politics of caste is more potent in India than the politics of class.

- The Left got overwhelmed by other regional powers that articulated regional aspirations in a more effective way.

And 2019 was the final blow for the Left in India, though a pretty severe blow had been dealt in 2014 as well.

The mass shift of the Left vote to BJP tells us something. The lesson probably is that the Indian voter is not as ideological as the Left would like. Moreover with the BJP embracing the economics of welfare very effectively, while at the same time holding out the promise of upward mobility, the Left’s class warfare rhetoric is less attractive than ever before.

The Left’s ideological attempt to oppose the masses in Sabarimala also served them poorly, resulting in a resounding defeat in Kerala as well. The Sabarimala fiasco points to one of the major failures of the "Left" in India — the tendency to underrate the religious character of the Indian masses.

Conclusion

That brings this survey to an end. Left-wing politics never really took off in India. There are many reasons for this: Indian diversity, the conservative Indian character, regional faultlines, caste, the Hindu predilection for order and non-violence. One can go on.

There is a lot to learn here for students of politics. Imported ideologies, removed from Indian culture and Indian realities, don’t work very well in India.

We will conclude on that note.

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Shrikanth Krishnamachary is a data scientist in financial services based out of New York City, whose interests include economics, political philosophy, Hinduism, American history, and cricket.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.