Politics

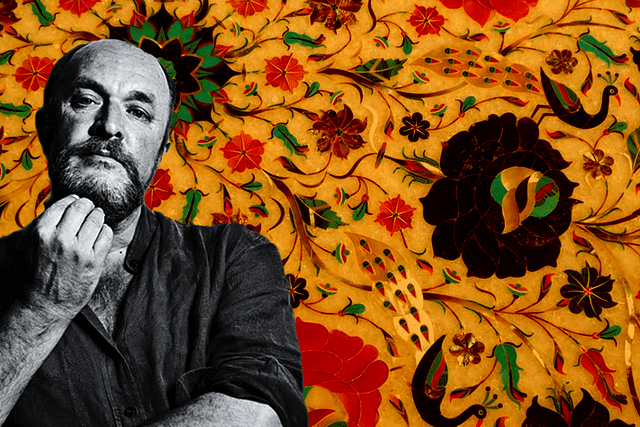

The Dalrymple Delusion: The Secret Of A Scottish Historian’s Mughal Love

B V Rudhraya

Aug 25, 2020, 12:19 PM | Updated 01:34 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In two earlier articles, we had covered William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy (Read here and here). We can now explore other facets of Britain’s favourite contemporary India historian.

Let us first take a detour. After decades in India, “Remarkably, Dalrymple is not fluent in any Indian language”.

Moreover, there is very little to indicate that Dalrymple understands the Hindu point of view on India. He may make claims to the contrary, but they do not indicate much more than a passing interest, an attempt to appear balanced.

This becomes a red flag because Western authors who have a poor understanding of what the world calls Hinduism rarely defend the rights of native India, leave alone provide an accurate portrayal.

Even Indian authors who are Anglicised, wearing elite 'liberal' or 'Marxist' hats, suffer from the same affliction.

Instead, what one reads is some version of the colonial liberal-Marxist theory, a deliberately distorted view of Indian history. Then it becomes natural to continue to find some method seemingly to criticise, yet essentially to whitewash, Islamic invasions and Mughal rule in India, at which Dalrymple is an acknowledged expert.

This does lead to the question: why would some British historians want to whitewash, at least partially, the horrors of Islamic invasions and tyranny?

Strangely, there is at least one good reason for it.

Essentially, British tyranny would not have been possible without piggy-backing on Islamic rule. Counter-factual history is difficult to assess, but one could venture the guess that the British would have had a far less chance of taking over Bengal in the 1750s, or any other part of India later, without the presence of the prior Abrahamic invader laying the groundwork.

Dalrymple’s Mughal love perhaps naturally flows out of that seemingly strange circumstance. Much later the British would carefully nurture and even 'gift' a part of Indian lands (ie, far North-West India and Eastern India, now Pakistan and Bangladesh) to the descendants of Islamic invaders, while pushing various theories including the trope that “there was no India before the British”, internalised by 'historians' coming out of Bollywood, no less.

The Oddness Of The Anarchy

Among the first mentions of caste in Dalrymple’s book on the East India Company, The Anarchy, comes when Dalrymple mentions how the British, when they took over Patna, set about looting it. But who did the looting? In his own writing, “…their army scum – dark, low-caste sepoys from Telangana…”

While it is unclear if these are taken from the source he references (Tarikhi-muzzafari), it is perhaps indicative of a shared (with Islamic medieval chroniclers) revulsion for the Hindu peasantry.

The reader might miss the simple idea that the British went about plundering not simply India, but especially India’s lower occupational castes of their livelihood.

Later, Indian students of all backgrounds would read in their liberal-Marxist school history books in independent India that it was Brahmins who 'oppressed' the lower castes.

“What madness to believe the words of the snake-oil salesmen of foreign origin over the experiences, deeds and faith of our own ancestors”, as has been highlighted here, using a mix of native and foreign sources.

Occasionally we see critiques of British troops, but it is not so much an “admission” but more a reflection of the contempt the British ruling classes of the time had, and perhaps still have, for their own 'low-born' compatriots.

Aristocratic British arrivals into India are often described with far more generosity. The English commoners who joined the East India Company (EIC) may in fact have been “prisoners, lunatics, whore-mongers and common drunkards”, as he mentions, but what does this tell you about the moral character of the British ruling elite and EIC shareholders who hired them and sent them off on an immoral 'trading expedition'?

When Dalrymple describes Shah Alam as ruling over a court of “high culture”, it is to be noted that native Hindus would not have described the debauchery of the Mughal courts in that way, while British arrivals and later British historians of the nineteenth century might have.

The early Marathas in the rugged Deccan might not have been described as “high culture”, but imagine describing Chhatrapati Shivaji as a “charismatic Maratha Hindu warlord”. A native son of the soil defending his land is a warlord?

Mentioning the Anglo-French wars in India serve the purpose of making it look like the British were simply the valiant 'last man standing' in a free-for-all. Basically, the idea here is that the triumphant British had earned the right to gloat as they fought all, and imposed order, over an 'anarchy', for which we should look back and be grateful. Secondly, since everyone was scrambling for India, why just blame the victorious ones (naturally, the British) who were the bravest and most organised?

Wrong on both counts. More accurate might have been that the natives of India were finding it very hard to survive the multi-century onslaught that came via Islam and then the church.

In fact, we might be “the only country in the world that has still largely retained our native identity”, something Dalrymple could have pointed out as a source of pride for India. But he doesn’t, as he feels no real connect to native Hindu India. His connect to India is its Mughals, his fellow-Abrahamists.

There is a section in the book where, over two pages, the British-led troops are compared to their opponents using words including “unruly”, “strict discipline”, “contempt and indifference”, “usual devious tactics”, and “bravery”.

The reader can guess which positive descriptions are used for which troops. It’s not that Dalrymple doesn’t offer compliments to the natives in other sections, but it is the subtlety by which he pushes the 'bravery' and 'courage' of the European, especially British, arrivals.

Furthermore, we have his fellow academic Maya Jasanoff pushing the idea that India was in the midst of a 'civil war', as told by “contemporary Indian chroniclers”. No, it wasn’t a civil war, and they weren’t 'Indian'.

The GDP Question

One of the references given is to the well-known Angus Maddison GDP (gross domestic product) estimates, where the British were better off 'per capita' than India by 1600 itself.

Here, perhaps, we can say the source itself might be questionable, and that it is not really Dalrymple’s error, but rather an inaccurate reference. Enquiry suggests that, though he was a sincere researcher, Maddison’s estimates are a tentative useful reference, not the final authority.

England was far poorer than India in 1600, backward technologically, so what conditions would make it better off 'per capita'? One possibility is that the Mughals were corralling the loot away from the natives out of India towards West Asia (multiple sources confirm this, including Will Durant).

The other option is that the British were themselves simultaneously colonising and looting some other part of the world, and able to catch up on a per capita basis by 1600. None of this is explored and, in this reviewer’s estimate, Dalrymple’s claim is unlikely to be true.

Further, Dalrymple, in a footnote, makes the claim that since England’s GDP per head was already higher than India’s (p. 411), it “…implies that the wealth in India in this period, as today, was concentrated in the ruling and business classes, and very unevenly distributed”.

Is this a subtle attempt to say England was more egalitarian than India? Or did he just miss the opportunity to say that northern India was far more uneven in its distribution of wealth, not just with the Mughal-subjugated Hindus, but also amongst the Mughals themselves?

The former would, of course, be true, and the latter surprisingly would also be true, as the Mughals, like earlier sultans, were not exactly egalitarian by any means.

He goes on to say that in the seventeenth century, India’s GDP per head was higher than in the 16th century India (per Maddison’s estimates), another clever way of saying the Mughals improved the economy.

One could object here too: at best, the foreign Mughal rulers, once they established paramountcy over northern India, were able to reverse the disastrous GDP slide that came with the Islamic onslaught on India over centuries, possibly because they had become a more stable power in the North.

In any case, this reviewer for one is not about to accept these conclusions without clarifications, whether from Dalrymple or Angus Maddison.

The Circuit

Let us get away from his book and take a look at his tours and speeches, which aren’t redeeming either. In a recent event, he spoke to an Indian audience offering them a version that sounded like the debunked Aryan Invasion Theory via the trope “India is a land of immigrants”.

Of course, he was careful to insert that the upper castes have genes from the Caucasus. He did not talk about the composition of pre-Islamic India and nor does he reveal that Hindu doctrine, unlike Christian and Islamic doctrine, does not approve of such crimes against humanity, whitewashed by some historians as 'migrations'.

As most of us know by now, the earlier Europeans and Africans who went to the Americas and Caribbean were not “immigrants”.

Arab Islamic imperialists out of Arabia and later into the regions of Central and West Asia were never immigrants, nor were their successors into India.

The Mongol hordes being held back in what is now Poland and Austria were not due to a lack of appropriate documentation. There is no proof that (some of) the modern native Hindus of India arrived into India on the back of a genocidal religion-inspired dogma.

Dalrymple also mentions members of his own family who were operative in India (not as immigrants, of course) but, as to the nature of his own family background, things do appear as if he has an incurable colonial hangover.

There are moments when it feels we should be paying more attention to Dalrymple, but not for the right reasons. Perhaps the next time one of our Indian liberal friend ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs’ over Dalrymple, a read-up of this article might wake them up from their Dalrymple Delusion. Till then, we will have to make do with his subtle Dalrympian distortions.

The reader is requested to read the two-part review here: 1 and 2, for additional references.

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

B V Rudhraya is an independent researcher, and has been published on YourAwesomeIndia and IndiaFacts.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.