Science

How India Is Using AI To Build The Internet For Local Languages

Karan Kamble

Jul 30, 2023, 11:15 AM | Updated 11:15 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Imagine a future where everyone, unimpeded by the language barrier, receives education in the language most familiar to them — their mother tongue.

With the medium of instruction squarely in their comfort zone, crores of Indians would be able to focus on knowledge and skill rather than worry about tripping over every step on a minefield of unfamiliar lingo.

Similarly, consider a time when people are better able to access services in critical areas like healthcare, banking, and law, free from the worries of communication, thanks to the ease accorded by a diverse language platter delivered through accessible technology.

Such an empowered future is firmly in the works, courtesy of an Indian government initiative supporting and coordinating wide-ranging efforts by a whole ecosystem of players, from researchers to startups, to ensure language isn’t a barrier for the world’s most populous country.

The Language Divide

For many, the internet may feel as ubiquitous as air. So connected are we to the world wide web that we gasp for that mobile data or WiFi signal when, to our anxious surprise, its supply diminishes, say, high up in the hills or in remote areas.

This perception, of course, doesn’t tally with reality. Only about 66 per cent of the world’s population is using the internet, according to the 2022 figures posted by the United Nations agency International Telecommunication Union (ITU). That’s not very “ubiquitous.”

The extent of internet connectivity falls further in countries categorised as ‘least developed’ (LDCs). Only 36 per cent of the LDC population used the internet last year.

While this internet access and usage gap is concerning in the face of the world wide web’s great promise for upliftment, it is likely to be comfortably bridged someday — as is the endeavour of, for instance, the companies building internet-enabling satellite constellations in space.

However, there is a different kind of internet “access” that is similarly necessary but not sufficiently catered to, especially for a diverse country like India.

The medium over which this access, or digital bridge, gets extended is not physical cables or electromagnetic signals but the good old written and spoken word.

Internet’s English Bias

English is the dominant language of the world wide web — it is used by over 54 per cent of all the websites whose content language we know. That’s a high figure for just about 18 per cent of the world that speaks the language properly — close to 1.5 billion speakers.

In contrast, Hindi, the world’s third-most spoken language, and India’s top-most, with about 602 million speakers globally and accounting for over 7.5 per cent of the world, doesn’t even feature in the top 20 content languages for websites. Only 0.1 per cent of all websites are in Hindi.

Hindi is only one of the 22 major languages in India, as recognised under the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India. Going by languages taught in schools, there are between 69 and 72. Considering the languages and dialects in which the radio network operates, there are 146. The Census of India 2011 identifies as many as 1,369 mother tongues.

Juxtaposing this whopping language diversity of India with the fact that about 70 per cent of the country still doesn’t speak or understand English properly, a strong case emerges instantly for building an internet that embraces the many languages of India.

This is more so the case considering the rise of internet users in the country. By 2025, India is estimated to have as many as 900 million active internet users — meaning those who access the internet at least once a month. This figure is only expected to move further north.

The paucity of content in India’s many local languages, therefore, is less an inconvenience and more a lapse. The language barrier to the internet needs to be bridged, just as the expansion of internet access, in terms of the ability to connect to broadband internet, is essential.

Mission Bhashini

Recognising this language hindrance, as also potential, for Indians and Indian-language speakers, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), Government of India, has been running a novel initiative called Mission Bhashini.

Short for BHASHa INterface for India, Bhashini first found a mention as the “National Language Translation Mission (NLTM)” in Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s Budget 2021-22 speech.

“This (mission) will enable the wealth of governance- and policy-related knowledge on the internet being made available in major Indian languages,” Sitharaman said, providing some context.

The mission came into being after it was recommended by the Prime Minister’s Science, Technology, and Innovation Advisory Council (PM-STIAC).

The idea was to leverage technology for the translation of content into Indian languages, with a focus on making science and technology accessible to all citizens in their mother tongue.

After Sitharaman’s announcement in February 2021, the language translation mission got the MeitY nod in October that year. The Digital India Bhashini Mission, as it came to be called later, received an allocation of Rs 495.51 crore for three years.

Early next year, in February 2022, the nuts-and-bolts work under Bhashini began, and the mission was formally launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 4 July, at the inauguration of Digital India Week 2022 in Gandhinagar, Gujarat.

Bhashini’s aim is to enable easy access to the internet and digital services for all Indians in their own language and increase the availability of online content in Indian languages.

At its core, the means to accomplish this aim is simply language translation through technology.

For this purpose, Bhashini has created an ecosystem, pooled in data and models contributed by the ecosystem into a shared repository, and encouraged the development of products and services in Indian languages by drawing from the open repository. This is an ongoing process.

The Bhashini ecosystem comprises government, academia, research groups, startups, industry, and even citizens, who are natural repositories of languages in India.

Within the ecosystem, the work in progress is building up abundant language data that can be used by researchers to develop artificial intelligence (AI) language models, on the basis of which startups, the industry, and government will build innovative products and services for citizens.

In this way, Bhashini is striving to enable a more inclusive and empowered future for all Indians.

Bhashini’s Great Potential

The translation mission will obviously transcend the language divide, since that is its primary motive, but it will also bridge the digital and literary divide along the way, according to Amitabh Nag, chief executive officer of Digital India Bhashini Division.

Digital India Bhashini Division, an independent business division under the Digital India Corporation set up by MeitY, is in charge of Bhashini implementation.

“We are enabling voice understanding; that means we are providing tools through which the machine can understand voice, automatically recognise the voice, and translate it to the person who understands other language,” Nag says.

Additionally, by enabling speech-to-speech communication through machines, Bhashini will be able to lift the barrier associated with literacy — the ability to read and write — by ensuring one can acquire knowledge and get things done through speech alone.

Consequently, many of the digital public infrastructures and goods which are already in place for the benefit of citizens will be able to cross the “last mile” hurdle and reach anyone previously thwarted by language, literacy, or technology.

Bhashini will have cultural significance, too — by helping preserve India’s rich knowledge and culture, which are alive and kicking in all its native tongues but missing from the English lexicon.

It will also foster greater innovation by helping expand collaborative research and development across India, after language has ceased to obstruct communication among individuals.

Furthermore, Bhashini will open up new economic opportunities for an aspirational India.

Indian businesses — including many young startups and especially those which are digital-native — will suddenly get access to a much wider non-English-speaking Indian market. This will especially benefit the innovative startups increasingly emerging from smaller cities and towns.

Technology Is Key

Technology is the primary vehicle over which language translation is to be delivered.

Bhashini has more than 70 premier technology partners on board within about 11 consortiums, all working to build language data and develop the AI models necessary for language translation.

The technology partners include many of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), the International Institutes of Information Technology (IIITs), the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), several Centres for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DACs), and some of the National Institutes of Technology (NITs).

With some of the best brains in technology joining forces to help the country transcend the language barrier, Bhashini is a truly mighty — also MeitY — technology showcase by India.

Nag believes Bhashini presents one of the largest use cases in the world for AI/machine language, data science, and API usage. (APIs, or application programming interfaces, enable applications to exchange data and functionality easily and securely.)

Fundamentally, the goal is to accomplish translation from one Indian language to another — among text, speech, and video.

The technologies principally serving this purpose are automatic speech recognition (ASR), optical character recognition (OCR), natural language understanding, machine translation (MT), and text-to-speech (TTS).

ASR, or speech-to-text, for instance, is the technology that allows computers to speak with humans by identifying and recognising the spoken word and then converting it to readable text format.

Text-to-speech (TTS), on the other hand, is the reverse: generating a speech output corresponding to a given text input.

Technologies like ASR and TTS, with the foundation of a large data corpus and high-compute infrastructure, can be put at the service of creating advanced machine translation systems, preferably made in India and for India.

“One of the major focus efforts of Bhashini is to ensure that we build indigenous deep tech — be it LLM (large language model), speech, MT, or TTS, and not piggyback on ChatGPT or other OpenAI models,” says Professor Hema A Murthy, who works at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at IIT Madras and is engaged predominantly in speech efforts for years.

“While all our models use deep tech,” the researcher says, “the fundamental difference is the use of a culture-specific approach, language family approach, to judiciously use deep tech — this ensures that we can do good deep tech with small amounts of data, hence less compute power, and raw power.”

Language Technology R&D

Machine translation work in Indian languages has been underway since the 1980s.

Some notable early projects include MaTra, developed at the National Centre for Software Technology (now C-DAC Mumbai), and Anglabharati, Anubharati, and Anusaaraka, developed at IIT Kanpur. (Anusaaraka later moved to IIIT Hyderabad.)

However, advancements in deep learning and processing power have propelled AI Indian language work in recent years, amplified further by the emergence of a country-wide unifying effort in Bhashini.

At least three years of preparatory work went into the mission before it was announced in February 2021.

Two pilot projects provided the initial spark. One was sponsored by the Office of the Principal Scientific Advisor (PSA) and the other by MeitY, both led by Professor Dipti Misra Sharma of IIIT Hyderabad, with IIT Madras and IIT Bombay as partners.

Under the PSA pilot, for which credit goes to Professor Rajeev Sangal of IIIT Hyderabad, a speech-to-speech translation system was under works for the translation of video lectures created under the National Programme on Technology Enabled Learning (NPTEL) into Indian languages.

“Within a year it was shown that it is feasible to use technology to make this happen,” Professor Murthy says.

The Ministry of Education then engaged with IIIT Hyderabad for the Swayam project.

The work involved transcription, translation, and subtitling of 82 courses, roughly amounting to 1,600 hours of video content, in English and eight Indian languages, covering various areas like law, taxation, and environment.

Eventually, lectures from both Swayam and NPTEL were reproduced in various Indian languages using the technology developed in the pilot stage.

IIIT Hyderabad’s engagement here was natural. Its Language Technologies Research Centre had long been at the forefront of technology development aimed at bridging the language barrier.

The MeitY-sponsored pilot, according to Dr S K Srivastava, dealt with the “development of ASR and speech synthesis systems at IIT Madras, translation among the Indian languages at IIIT Hyderabad, translation from English to Indian languages at C-DAC and IIT Madras."

Before Bhashini, MeitY was supporting research activities in language technology since 1991 under the Technology Development for Indian Languages (TDIL) programme.

The TDIL was initiated with the aim of developing information processing tools and techniques to facilitate human-machine interaction in Indian languages, as well as building technologies to access multilingual knowledge resources.

TDIL’s longtime chief Dr Swaran Lata, now an advisor to the Bhashini mission, initiated mission-mode consortium projects for these efforts, giving impetus to collaboration.

One of the notable projects executed under TDIL was the Mandi Project. It led to a system that helps farmers keep up with the latest prices of agricultural commodities and the weather using only a feature phone and while speaking in their native tongue.

In another instance, a TTS synthesis system integrated with a screen reader was developed, which enables visually challenged people to interpret and perform computer operations with an audio interface. Supporting 13 Indian languages, the system is integrated into some government websites.

Two other TDIL projects warrant a mention: Sampark and Anuvadaksh.

The Sampark machine translation system was developed by a consortium of institutes led by IIIT Hyderabad for translation from one Indian language to another, covering nine languages.

Anuvadaksh was developed by a consortium led by C-DAC Pune for translation from English to some Indian languages like Gujarati, Oriya, Tamil, Bodo, and Bengali.

Such R&D work served as a precursor to Bhashini, with many of the partner institutes now using that experience to develop language translation tools under the national mission.

Translation Tools

The Bhashini mobile application, available on both the Android and iOS mobile operating systems, and the web service Anuvaad are both helpful and easy to use.

The mobile app can be used to translate text and speech from one Indian language to another and has a feature using which any two persons speaking different languages can communicate with each other in almost real time.

The text translation feature on Bhashini supports 11 languages, including Assamese, Gujarati, Kannada, Punjabi, and Tamil, with a further 11 languages in the beta stage.

The voice translation and conversation features support the same 11 languages, with two languages Bodo and Manipuri in the beta stage.

Anuvaad is a web service — meaning it can be accessed on a web browser — supporting text-to-text and speech-to-speech translation in 13 languages.

IIT Madras and IIT Bombay host similar translation tools developed under Bhashini.

The Speech Lab at IIT Madras (NLTM R&D) features four tools on its portal — ASR, speech-to-speech (S2S), text-to-speech (T2S), and video-to-video (V2V). (The names indicate the nature of translation.)

The head of the Speech Lab is Professor Srinivasan Umesh, who is leading the ASR efforts for the Bhashini mission and is a co-coordinator for the speech technology consortium of 21 institutions.

Previously, he led a multi-institution consortium to develop ASR systems in Indian languages in the agriculture domain, between 2010 and 2016.

IIT Bombay’s text-to-text and speech-to-speech translation systems are also available as web services. The languages supported are Hindi, English, Marathi, and Nepali.

The systems were developed by the Computation for Indian Language Technology (CFILT), a distinguished centre for natural language processing (NLP) under the leadership of Professor Pushpak Bhattacharyya.

The premier institute has two bidirectional text-to-text machine translation systems, called Ishaan and Vidyaapati, in the development stage. They will cover languages such as Assamese, Bodo, Manipuri, Nepali, Konkani, and Maithili.

In a little something different, a conversational AI has been developed under Bhashini through experimental integration with WhatsApp and OpenAI’s ChatGPT-3.

Using the Bhashini WhatsApp chatbot, one can ask a question in their language and receive a response in the same language. The input can either be text or voice and the output arrives in the form of both text and voice. Currently, Hindi, Gujarati, and Kannada are supported.

One can use the chatbot to enquire about a government product or service. In a popular demonstration of the chatbot, one plays a farmer and asks questions about the PM Kisan Yojana in Hindi and hears back responses in Hindi.

This chatbot speaks to an earlier point on how Bhashini is able to bridge the language, literacy, and digital divide and make people’s lives easier.

Real-world Applications

Several AI language applications based on Bhashini APIs have taken shape over the last couple of years, thanks to the more than 800 AI models on the national platform, many of which are in the process of being integrated into various services.

Jugalbandi is a free and open platform that combines the power of ChatGPT and Indian language translation models.

It drives WhatsApp and Telegram chatbots using which anyone can ask about 121 government schemes in 10 Indian languages. Farmers are advertised as the primary beneficiaries.

In the future, Jugalbandi can potentially power WhatsApp and Telegram chatbots to help democratise access to legal information and bring quality healthcare to citizens.

It has received the endorsement of Microsoft chief executive Satya Nadella. “The rate of diffusion of this next generation of AI is unlike anything we've seen, but even more remarkable is the sense of empowerment it has already unlocked in every corner of the world, including rural India,” Nadella said earlier this year.

Anuvaad, developed by AI4Bhārat at IIT Madras, is an AI-based open-source platform for the translation of documents into Indic languages at scale. The service supports 13 languages and leverages OCR and NMT to accomplish end-to-end document translation.

Its maker, AI4Bhārat, has been building open-source language AI for Indian languages, including datasets, models, and applications, as a public good. It serves as the Data Management Unit for Bhashini.

From its inception in 2019, using AI to connect Indians who speak different languages has been one of AI4Bhārat’s focus areas. Its technology efforts are primarily led by Professor Mitesh Khapra, Pratyush Kumar, and Microsoft researcher Anoop Kunchukuttan.

Their tool Anuvaad has found use in the Supreme Court and High Courts of India as “SUVAS,” in the Supreme Court of Bangladesh as “Amar Vasha,” and in the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) under the Ministry of Education as “Diksha.”

Anuvaad has helped digitise and translate more than 20,000 legal documents already. It was developed for the judicial domain, but has found general-purpose use over time, as well.

It is also likely to be integrated with the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), as indicated by UIDAI deputy director general Alok Shukla, speaking on ‘Bhashini and multilingual internet’ earlier this year on the occasion of Universal Acceptance Day.

“I was impressed with the quality of the translation,” Shukla said, adding “Definitely, Bhashini is going to help us.”

The proliferation of video content on the web has raised the need for transcription. For this purpose, there is Chitralekha, also developed by AI4Bhārat for Bhashini.

Chitralekha is an open-source platform tool for video subtitling across various Indic languages. It supports multiple input sources, such as YouTube or local storage.

The platform automatically creates time-stamped transcription cards, which can be edited, and enables translating the transcription into English and 12 Indian languages.

At a time when so much learning happens over video, a platform like Chitralekha can make learning accessible to anyone regardless of the video’s original language. It is being used to make the higher education course content under NPTEL available in various Indian languages.

The IIT Bombay initiative Project Udaan is similarly helping overcome the language barrier in the Indian higher education system.

Led by Professor Ganesh Ramakrishnan, Udaan is enabling the translation of textbooks and learning materials across English and all Indian languages. Translation from English to Marathi and Malayalam is currently underway.

The project is expected to benefit the more than 65 per cent of over 1 crore students appearing every year in Class 10 and 12 exams of various school boards who are from non-English-medium schools.

Using their machine translation framework, Udaan has been able to speed up the process of translating technical books, as acknowledged by the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE).

What Lies Ahead

For Bhashini, voice is the way forward across areas — payments, banking, education, health care, and retail, to name a few.

“We believe that voice-enabled technologies are going to be the future, they are going to be the next big revelation,” Professor Umesh of the Speech Lab, IIT Madras, has said.

While language translation over voice is already a reality, making payments using voice is a particular area of interest for Bhashini. Digital payments are, after all, soaring in popularity, with the value of digital transactions in India expected to reach $135.2 billion by the end of 2023.

The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), an umbrella organisation for all retail payment systems in India, is reportedly working with AI4Bhārat to develop a system for voice-based merchant payments and peer-to-peer transactions in Indian languages.

This will enable feature phone users to benefit from digital payment innovations like the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), currently enjoyed only by smartphone users.

“We are working hard to actually ensure that we are in a position to make UPI speech-enabled. ‘Dus rupay pay karo (pay Rs 10)’ is the idea and you get a response by voice,” Nag says, adding, “We are not far away.”

Similarly, Bhashini is working with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to enable voice-based banking, and with the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) for voice-based retail.

Bhashini is also looking to make the national telemedicine platform eSanjeevani multilingual.

eSanjeevani, which facilitates quick and easy access to medical professionals over the smartphone, is bridging the digital health divide. Bhashini can elevate it further by helping bridge the language and literary divide, as well.

Education is a crucial potential area of impact for Bhashini. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 recommends the use of the mother tongue as a medium of instruction in schools until at least Class 5, but preferably up to Class 8 and beyond.

Even under the Right to Education Act of 2009, it is stated that the “medium of instructions shall, as far as practicable, be in child’s mother tongue.”

Bhashini is a natural vehicle for these goals. “Making educational apps multilingual will be in line with NEP, and perhaps make the unskilled youth skilled,” Professor Murthy says, noting that India is expected to have the largest number of unskilled youth under 25 in 2029.

As for government services, India’s mobile governance app UMANG, short for Unified Mobile Application for New-age Governance, is already accomplishing direct benefit transfer using Bhashini APIs.

The day is also not far when one is able to make voice-based complaints on the grievance redressal app Centralised Public Grievance Redress and Monitoring System (CPGRAMS).

Beyond the fantastic impact on individuals, Bhashini might also play a significant role on the regional and global stage.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke earlier this month about sharing Bhashini within the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) — an intergovernmental organisation comprising eight member states that speak different languages.

While addressing the SCO Summit 2023 in Hindi, he said, "We would be delighted to share India's AI-based language platform Bhashini with everyone to remove language barriers within SCO. It can become an example of digital technology and inclusive growth.”

Such is the wide sweep of Bhashini — from enabling an individual at home to upskill using just their native tongue to facilitating critical communication among world leaders on the most pressing matters affecting a region or the world.

It can help build an India where knowledge is accessible to all, with its citizens truly included, empowered, and aatmanirbhar (self-reliant) in the real sense.

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Karan Kamble writes on science and technology. He occasionally wears the hat of a video anchor for Swarajya's online video programmes.

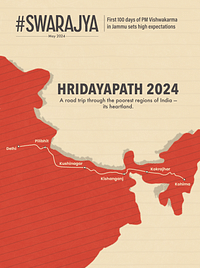

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.