Hindu-Jewish Dialogues: A Model For Honest Discourse

Hindu-Judaism dialogues are free of any secret agenda, unlike many Christian, Islamist, and even Marxist ‘dialogues’, which are often a camouflaged call for proselytising.

Hindus and Jews have mutual respect for each other’s dissimilar religious practices.

A remarkable quality of Hindu-Jewish dialogues is that they are largely free of any proselytising agenda. Here are two religions, ancient cultural traditions, that appear entirely different and even mutually exclusive. Further, the Hindu society has a chequered past and a not-so-comfortable present with two expansionist monotheist religions, Christianity and Islam, claiming to have originated from Judaism.

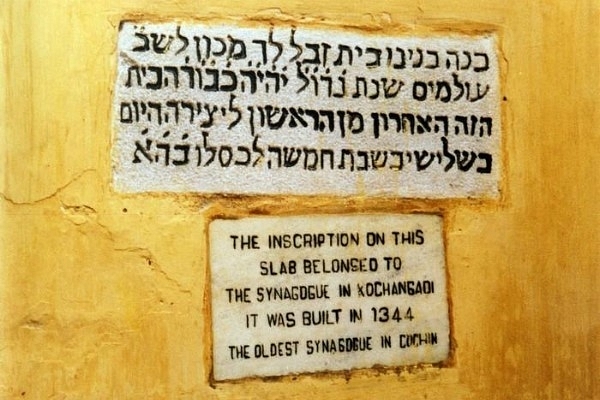

There is also the past experience of the Jewish in India, perhaps the longest, and remarkably free of anti-Semitism. Add to this the fascination most Hindus have for Israel, both for its incredible achievements of making ploughshares out of swords and successfully fighting a battle against all odds.

All these aspects make Hindu-Judaism dialogues a very important phenomenon. The dialogues and studies provide us with a model where the comparative analysis can be done largely free of any agenda. This cannot be truer having especially seen firsthand many Christian, Islamist, and even Marxist ‘dialogues’, which are often a camouflaged call for proselytising, having read many of the comparative studies of religions by evangelical strategists from colonial ages to Clooney and Witzel, which are essentially scouting expeditions for studying the fault lines and strategies for appropriation and conversion.

The Hindu-Jewish dialogues serve as a model where the similarities and dissimilarities of religions are observed largely free of any agenda, and with what the late Swami Dayananda Saraswati (1930-2015), head of a traditionalist Vedanta school, called ‘mutual respect’ accommodating mutual differences.

In this respect, The Jewish Encounter with Hinduism by Alon Gosthen-Gottstein (Palgrave, 2016) becomes important for Hindus and Jews who are enthusiastic about mutual dialogue and understanding. Before writing this book, Gosthen-Gottstein has explored one of the most troublesome aspects that might emerge in Hindu-Judaism encounter, Avoda Zara, or the problem of foreign deity or idolatry. The author’s approach to the problem is honest and respectful. His “is not an argument for Hinduism not being Avoda Zara. Rather, it is an argument for applying a richer and more nuanced method and for rethinking the very category of Avoda Zara.” (The Same God, Other God: Judaism, Hinduism and the Problem of Idolatry, Palgrave 2016)

The ‘mutual respect’ espoused by Saraswati is not an easy principle – at least among the academia of Western religious studies. It needs a great level of understanding of the other with the deepest level of empathy. The following conclusion that Gosthen-Gottstein derives for the Jewish understanding of Hinduism from a deeper Jewish spiritual point of view shows the enormous strength and wisdom one needs for the exercise of ‘mutual respect’:

The subject of idolatry can itself become the victim of an idolatrous attitude. ... The encounter with another religion is also one that requires an understanding of the heart, lest our approach to the other religion itself become a graven mental image. ... We need to shift the idolatrous attitudes in us as a condition for discovering God in the other. Herzel Hefter has made us aware of the problem of idolatry within, as it relates to the Hindu concern with the dynamism of the image. ... To view the other primarily through the eyes of Avoda Zara is to make our own look deadly, cursed by the fixity of perspective that sees the Other as other. What we need is a different regard, one that removes the idolatry within the heart as a condition for engaging the other. ... We have moved from ruling to discernment, and with Rabbi Leiner we move from legal principles to the understanding of the heart, open to the Divine. Any encounter must be lived in this way. Hinduism makes it particularly easy for us to do so. In important ways, the encounter with Hinduism may force us to be less idolatrous in our own view of reality.The Jewish Encounter with Hinduism by Alon Gosthen-Gottstein

The fact that the passage is meant primarily for Jewish readers makes it beautiful and forceful and, more importantly, relevant for all humanity.

If the so-called ‘idol worship’ of Hindus has been perceived by insightful Jews as not the idolatry abhorred in the Hebrew sacred texts, Hindus need to realise that the monotheism of Jews is qualitatively and spiritually different from the expansionist monotheism of Islam and Christianity. The strong spiritual dimension that the centuries-old tradition of Kabbalah has imported to the monotheism of Judaism should reinforce this for Hindus. As author Ram Swarup pointed out in another context, Hindus need to understand monotheism as the expression of unity (as in the case of Judaism) and distinguish it from the political ideology of expansionism, as is the case of evangelical monotheism. (As a spin-off benefit, such an understanding will also immunise Hindus against the proselytising attempts which misuse Hebrew Bible as Old Testament).

In the book under review, which deals with the ‘Jewish encounter with Hinduism’, the chapter on what the current students can learn from the ‘Jews of India’ leads to an important observation:

Rather than highlighting the idolatry, strangeness, and otherness of their Hindu neighbors, Indian Jews seem to have reciprocated the acceptance and tolerance they enjoyed through an attitude of respect. ... Surely the Jews must have realized how different the religious landscape of the Hindus is. How come, then, that this difference is not expressed in their writings? ... If Jews came to view Hindus as monotheists, who worship different representations of One God, as Hindus could understand themselves, the level of tension in relation to Hindus would obviously be lower than if they showed concern about forbidden idolatrous worship. It is noteworthy that other travelers, even while they report on Hindu practices that constitute idolatry from the Jewish perspective, are silent on the attitudes of the local Jewish community. The tone is descriptive and we do not hear of a criticism or rejection of Hindu practices, as part of the prevailing attitude of the Jewish community.The Jewish Encounter with Hinduism by Alon Gosthen-Gottstein

It is not whether Hindus subscribe to this monotheist perception that is important. What is important is that the Jews of India have been perceptive enough to see no negativity in the completely different manner of religious practice they encountered in India.

From here, the author moves to Sarmad Kashani (1590-1661), a mystic of Jewish origin who was martyred in Delhi by Aurangzeb. Gosthen-Gottstein points out that “the Jewish authors who wrote on Sarmad spoke of him approvingly, owning and embracing him, or at the very least appreciating his positive contribution from a Jewish perspective (p 31)”. This is despite the fact that the religious boundaries of Sarmad defy clear definitions. In 1966, a book on Sarmad was published by the Radhasoami sect, which was written by an Indian jew, I A Ezekiel – Sarmad (Jewish Saint of India). The book portrays Sarmad as a ‘perfect master’ reflecting the principles of Radhasoami sect itself. Then comes Roger Kamenetz’s bestseller, The Jew in the Lotus, where Kemnetz “draws a comparison between Sarmad and a contemporary figure — the Jewish-Hindu teacher Ram Das”. Gosthen-Gottstein quotes Sarmad which, he points out, could provide even stronger justification for comparing Ram Das and Sarmad:

What shortcoming didst thou find in the Prophet and in God,

That thou turned thy face away from God and the Prophet

And became a disciple of Ram and Lakshman

The analysis of Sarmad could have benefited more from, perhaps, the most comprehensive study on Sarmad, Sarmad His life & Rubais (1978), an analysis of his poetry and biography, published by Hanumanprasad Poddar Smarak Samiti, Gita Vatika, Gorakhpur. Written by Lakhpat Rai, editor of Kalyana Kalpataru (a magazine published by Gita Press), the book makes an in-depth study of Sarmad and draws parallels from Hindu scriptures to Francis of Assisi and places Sarmad as a universal mystic.

Prof Nathan Katz, who visited the samadhi of Sarmad as part of Dharmasala dialogue recited Kaddish on Sarmad’s tomb, “a recognition of his being the group’s predecessor in dialogue, a culmination of the image of Sarmad the Jew, independently of the Muslim context within which it is offered”. Katz himself wrote in 2000 an article discussing the religious identity of Sarmad, where he emphasised “Sarmad’s rejection of religious practice and piety, in favor of a higher spiritual principle” and by extension “affirming his simultaneous identity as a Jew, a Hindu, and a Muslim”. Gosthen-Gottstein points out that “this kind of multireligious identity comes through in relation to another disciple of Sarmad’s, the prince Dara Shiko”, who addressed Sarmad as his “master and preceptor”.

While it is easy to portray Shikoh (and Sarmad) as without any religion, a deeper study suggests a better possibility. Late D Malik Mohamed, in his detailed study on Hindu-Muslim syncretic traditions, points out how Dara Shikoh considered “in a certain sense the Upanishads” as “even superior to all other heavenly books, because the divine message is expressed in them in the most explicit fashion” and that “in saying this Dara Shikoh abandons the cherished Islamic conviction that Islam is in the eyes of Allah, the only true faith (Sura 3:19) and that Quran is a clear, readily understandable book” (The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India, 2007, p 57). So the non-religious boundaries of Sarmad (and Shikoh, by extension) that Katz identifies, is also the recognition of a deeper spiritual unity beyond the outward differences, which is a characteristic feature of Hinduism.

In this regard, the Hindu-Jewish summit dialogues that happened in 2007 and 2008 assume importance. They are critically evaluated by the author along with his personal assessment of the value of Hindu-Jewish interaction. This aspect needs an elaborate study in itself and is continued in the second part of the article.

(Read the interview with Prof Nathan Katz published in Swarajya.)