Culture

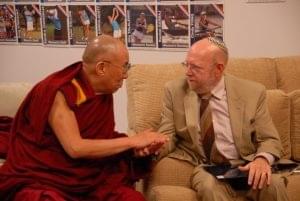

The One-Man Bridge Between Indic And Jewish Traditions: An Interview With Prof Nathan Katz

Aravindan Neelakandan

Oct 04, 2016, 12:40 AM | Updated 12:40 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

.jpg?w=310&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

“I celebrate my personal and professional links between India and Israel. I have been ahead of the curve in this, and it is with a deep sense of gratification that I see others moving in that direction,” Dr Katz wrote in his autobiographical story of how he moved through various spiritual traditions and at last returned to his spiritual home in the spiritual traditions of Judaism.

Hinduism, with its belief in many forms of the divine, and Judaism, with its belief in the ‘one divine’ source, at the surface may look different. However, for Dr Katz, who recently retired as the Bhagawan Mahavir Professor of Jain Studies at Florida International University, the dialogue between the Chief Rabbi of Israel and the then head of the Hindu Dharma Acharya Sabha in 2007 validated some of his own discoveries of certain spiritual truths during his personal pilgrimage through world spiritual traditions. This was that the same divine is worshipped in different spiritual traditions and that the theo-diversity we find in the planet is part of the intentional play of the divine.

Dr Katz has been working for decades in exploring the Hindu-Jewish relations at various levels – historical, cultural and spiritual. At a time when most of the academic Hindu/Indic studies in the West suffer from shades of Hindu-phobia, the approach of Dr Katz has been refreshingly different. Given below are excerpts from an interview with Swarajya he gladly agreed for.

Throughout your career as an academic you have shown focused interest in Hindu (Vedic Buddhist Jain) or Indic streams of spiritual traditions. Is there any specific reason for your motivation that you would like to share with our readers?

This is my mystery. I utterly cannot explain my lifelong fascination with India. My mother, may she rest in peace, told me that at the age of five I came to the Shabbat dinner tables and announced to my family that I was going to India “at my earliest opportunity.” And I did, 15 years later.

Can you give us glimpses of how your personal spiritual journey and your career as an academic studying another spiritual tradition interacted in your life?

I come from a traditional Jewish family, but when I became a teenager it was the 1960s and I disobeyed authority at every opportunity, rebelled in civil rights and anti-war protests, and became enamored of eastern spiritual traditions. I meditated, chanted, became macrobiotic, made pilgrimages, went to rock and roll concerts – the whole nine yards. It was a complex transformation that culminated when my wife and I spent a year with the Jews of Cochin.

Can you tell us about the academic bridge that you created for Indic-Judaic studies and how it is evolving today?

I had my first sabbatical leave in 1983-84, and I was researching the political ideas and behaviours of the Buddhist monks of Sri Lanka. As soon as my wife and I got there, the civil war had just broken out, so my topic was mooted. After some time in Sri Lanka, we decided to take a vacation, and we opted to go to Cochin. I had heard of an ancient Jewish community there, and also that Kerala is very beautiful. We quickly learned that the great community was in the process of extinction and that there was no book written about them. We went back to the US and read everything to be found about them, and started brushing up my Hebrew. Two years later we were back in Cochin on a senior Fulbright research fellowship. We stayed in Jew Town for a year, living in a Jewish home, taking our meals with our local co-religionists, praying in the synagogue. In short we lived the life of observant Sephardic Indian Jews. It was only after we left for Israel that we realised what had happened to us. Much to our surprise, we had internalised this religious life. I had intended to spend a year or two writing the book, but once we’d gotten in that deep there was no turning back. It was risky for a young assistant professor to switch fields of research, but my wife advised me to follow my heart, and that was the beginning of Indo-Judaic Studies!

What is the difference between the way the Genesis is generally understood by most of us here in India: the creation by the creator, corruption of Eve and the fall, all which form the basis of the so-called the original sin. Does Judaism subscribe to the idea of original sin which is popular through the Christian mythological rendering of the Genesis story.

No, this is not how we see it. Chava (Eve) and Adam disobeyed G-d by “eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.” This is interpreted in many ways, yet to me the key notion is free will (bahirat). By taking this knowledge, Eve and Adam became responsible moral agents, which is to say they became fully human. Freedom means the freedom even to disobey G-d. The possibility of doing evil is what allows us the freedom to do good. Maimonides writes that free will is perhaps Judaism’s most central notion.

Can you give us an insight into the relation between blood sacrifice and the original sin? This is important because often Hindus are given to understand that sacrifices are done in Judaism to repent for the original sin and Jesus came as the replacement for all the lamps. In fulfilment theology this is also extended to Hinduism.

No, Judaism has no concept of original sin. There are sins and when the Holy Temple stood many sins could be atoned through sacrifices of certain animals, birds, fruits and other agricultural products. After the destruction of the Temple, now prayer, repentance, and charity are our avenues to atonement. Early Christians reinterpreted the entire atonement theme in view of their original sin doctrine; sin became elevated to a cosmic principle, and atonement was viewed through their incarnation-resurrection drama. Perhaps, there is no point where the profound differences between Judaism and Christianity are more pronounced.

Does Judaism have a concept of Satan? If so, from when did it evolve and how it differs from the concept in both Christianity and Islam?

A satan (“adversary”) is a spiritual force that opposes our own spiritual and moral life. There is no one capital-S Satan. One teaching is that whenever we do something wrong, we create a satan that leads us to more sins and testifies against us in the heavenly court. When we do virtuous actions, we create angels that help and guide us.

Does Judaism have a concept of reincarnation? What is the view of Judaism with respect to soul in non-human existence?

Yes, gilgul is an important element in Jewish mysticism. The whole view of gilgul is that at least some part of our soul returns to this world to tend to unfinished business. It could be a kind of punishment, or it could be learning more and perfecting oneself. This is called tikkun. In some cases, one’s tikkun may be as an animal or fish. There are many Yiddish folk tales based on this concept.

You stated during the Jew-Hindu interaction on 11 September, 2016 that every word in Torah exist with 70 different meaning. Do you see a parallel to the Saptabangi in Jain philosophy where fundamental reality at all levels exists in possibilities of seven states -not in terms of the numerical parallels, but the very perception of reality?

It’s a very interesting question. Yes, every idea in Torah has 70 aspects or interpretations. I can see a parallel to Anekantavada of Jainism, that truth transcends our limited understandings.

Free thinkers have always been happy to show the 'God' of 'Old Testament' (a term insulting in itself) as a tribal God who kills other people etc. But what is the real Jewish conception of G-d in Hebrew Bible and how it differs from the way God has been depicted in Christian version? Does the distortion come from removing the multiplicity of meaning and making it 'the text' of a linear narrative?

I am not so interested in approaching this question as an historian, one who can trace the changes and developments in doctrines through the ages. As this is taught, the G-d of our Tanakh (Bible) Is the one G-d of the universe. The apparent paradox is that the G-d of the universe is also the “G-d of Abraham, G-d of Isaac, G-d of Jacob,” which is to say the G-d whom we know through our text, our history. Perhaps it was the prophets of the Babylonian Exile who first make explicit that the G-d Who redeemed us from slavery in Egypt is the same G-d Who guides the Babylonians, indeed the entire universe.

I would refer you to Maimonides’ 13 Principles of Faith (see the end of the interview) where we get as clear an understanding of G-d as we can formulate. This being said, Maimonides also wrote that G-d is “the knower, the known, and the knowledge” about whom nothing could be said or predicated. I once had an MA student trying to write a thesis comparing Maimonides with Shankaracharya. He managed to learn enough Sanskrit, but ran out gas when he started on Hebrew!

Can you elaborate upon the nature of Shekinah? Is there a traditional space for eco-feminine reading of Torah?

The Shekhinah is G-d’s presence in this world. It is taught that the Shekhinah resided in the temple, and when the temple was destroyed the Shekhinah went into exile with the Jewish people. The Shekinah is often understood as the female, and today many people try to connect her with Shakti or with mother Earth, etc.

Einstein famously said that his G-d is the G-d of Spinoza. Can you elaborate on Spinoza and his relation to Judaism?

Spinoza, as your readers may know, was excommunicated by his Amsterdam community for heresy, namely the heresy of pantheism, which is incompatible with traditional Judaism. That being said, he was nevertheless highly influential among maskilim (Jews of the enlightenment or secular Jews). He has been called the father of Jewish modernism.

Can you provide an insight into ecological aspects of Jewish thoughts? Are these ideas derived from Torah and do they have a bearing on the way Israel develops green technologies?

There is a lot of serious thinking being done about Judaism and ecology. Originally as the religion of an agricultural society, quite naturally Jewish law regulates our relationship with nature. For example, in the Land of Israel every seven years we are required to let our fields go fallow. Many of our festival observances involve using natural items in our synagogue services, such the “four species” (willow, myrtle, palm, and citron) during the fall harvest festival of Sukkot. Nowadays, scholars and theologians are thinking about how to apply these ideas to today’s environment. Israel, of course, is at the very forefront of water desalinisation, drip agriculture, solar energy, and so on,

Why should India be important to the Jew in his or her spiritual historical memory - not just to Jews who lived in India but to all Jews perhaps as the one land free of anti-Semitism?

One very important thing to consider is that India has always been kind to us. After three decades of independence and India’s infatuation with the Non-aligned Movement (NAM), India has become an important trade and cultural partner. And most Jews know that India has warmly embraced its tiny Jewish populations for a thousand years and more. We are building on that ancient friendship.

Why should Israel be important to the Hindus? Not merely because we face the common problem of terrorism but in a deeper spiritual sense as a land where an indigenous spiritual tradition has survived, reclaimed the lost promised land, and now flourishes.

Judaism and Hinduism have many parallels. Indigenous peoples develop a unique relationship to the home, unlike what is found in missionising religions. We share such deep connections to our homelands. We pray in an ancient sacred language, we follow our own dietary codes, we maintain our hereditary priesthoods, we honour family and learning. Yes, there are practical issues today – agricultural technology, IT, space exploration, counter-terrorism and intelligence, trade, and much more. But because of our shared history, our contemporary relationship is deeply grounded and is not simply a matter of mutual interests.

How do you propose to develop the organic and spiritual links between these two ancient people?

By talking, writing, visiting, lecturing, and leading Jewish-interest tour of India. And in my academic life I have written many books and articles on this topic, started up the Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, and have trained a number of graduate students.

~*~

‘These two themes’, says Dr Katz in his autobiographical account meaning, his ‘extreme sense of being at home in India’ and his ‘experiences of deeper levels of Jewish prayer’, are the ‘warp and woof of his life’. He is neither claiming a monotonous sameness nor crediting or discrediting one tradition over the other. In his return to Judaism as his spiritual home, he is not making a Malhotran U-turn. He respects diversity and through that he provides a framework to study one spiritual culture by another with mutual respect. He concedes that ‘some of the practices of Hinduism cannot be affirmed from a Jewish standpoint’ and yet he points out that a person raised in Hindu culture inspires a Hindu as well as non-Hindu alike. Hence as a Jew he expresses his respect for Hinduism: ‘Hinduism creates a cultured human whose actions honour both humans and our Creator’.

The Hindu-Jewish dialogue can provide the model for basic non-aggressive, non-expansionist mutually respecting dialogue which can provide the basis for a harmonious co-existence with all the differences that humanity possesses. Dr Katz is at the forefront of forging that model. Hindus and Jews recognise this contribution of Dr Katz and that explains why he is simultaneously an adjunct professor of Hinduism at the Hindu University of America in Orlando, and academic dean at the Chaim Yakov Shlomo College of Jewish Studies, an Orthodox rabbinic seminary in Miami Beach.

We at Swarajya wish that the seeds he sows which have already started growing, bear fruits not only for both Hindus and Hebrews but also to all the indigenous spiritual traditions of the planet.

Rosh Hasannah!

Further notes and resources:

On 11 Sptember 2016, on the day of Universal Brotherhood day when Swami Vivekananda addressed the world parliament of religions, a section of disciples of Swami Dayananda Saraswathy, who was the head of Hindu Dharma Acharya Sabha initiated a dialogue with Jewish scholars. The interaction at this event which was named the first Hindu-Jewish alliance talk's questions were, in part, guided by Dr Katz's chapter "An Introduction to Judaism for Hindus"

· For further reading – the autobiographical account of his spiritual pilgrimage: Nathan Katz, Spiritual Journey Home: Eastern ,Mysticism to the Western Wall, KTAV Publishing House, 2009

· The 13 principles of faith, which Prof. Nathan mentions in the interview are:

1. The existence of God;

2. God's unity and indivisibility into elements;

3. God's spirituality and incorporeality;

4. God's eternity;

5. God alone should be the object of worship;

6. Revelation through God's prophets;

7. The preeminence of Moses among the prophets;

8. The Torah that we have today is the one dictated to Moses by God;

9. The Torah given by Moses will not be replaced and that nothing may be added or removed from it;

10. God's awareness of human actions;

11. Reward of good and punishment of evil;

12. The coming of the Jewish Messiah

13. The resurrection of the dead.

· I express my gratitude to Ms. Kathleen Reynolds for introducing to me Prof. Nathan Katz and for catalyzing the interview by giving valuable inputs and pointers. A yoga teacher she has been active in networking Hindu and Jewish scholars and activists. Her url is: https://lookingglasshouseyoga.com/

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.