Economy

India's Critical Minerals: Why Does It Take 15 Years To Dig Up What's Already There And Ours?

Adithi Gurkar

Oct 25, 2025, 09:57 AM | Updated 11:11 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Beneath India's ancient peninsular shield lies a geological inheritance that should position the nation as a critical minerals superpower. Rare earth elements, lithium, nickel, titanium (the raw materials that fuel everything from wind turbines to fighter jets to smartphone batteries) rest in abundance across a landmass that was once part of Gondwanaland, the southern fragment of the supercontinent Pangaea.

The numbers tell a compelling story. India holds approximately 6.9 million metric tonnes of rare earth reserves, the third-largest in the world. The country has around 30 critical minerals, with significant deposits scattered from the lithium fields of Karnataka's Mandya district to the monazite-rich coastal sands of Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Odisha.

Yet this geological fortune remains largely untapped, was locked beneath technological deficits, and frameworks that seemed designed to discourage the very exploration they claim to promote. However, the recent policy changes, especially those post 2023 have marked a new dawn.

"India has done a stupendous job when it comes to mapping and preliminary exploration," Channamallikarjun B. Patil, founder of GeoExpOre, tells Swarajya. "Ninety-five to ninety-eight per cent of the country has been covered in this regard, thanks to organizations like the Geological Survey of India, the Mineral Exploration and Consultancy Ltd, and the Atomic Minerals Directorate."

This groundwork positions India to accelerate into the next stage of mineral development

"This is a very basic indicator, and it does not provide sufficient data. What the world wants to know is how much of these critical minerals India truly holds and where exactly they are present."

While China Was Watching, The World Was Sleeping

The contrast with China reveals not merely a gap in capability but a chasm in strategic vision.

While the world fixated on Gulf oil, China quietly recognised the value of rare earth elements decades ago. Today, the dragon controls approximately 95 per cent of the global rare earth market and its technology (elements that serve as raw material for virtually all clean energy technology, defence systems, electric vehicles, batteries, and consumer electronics).

The irony cuts deeper. Despite possessing substantial domestic deposits, China has diversified its supply chains over 35 years, establishing control over mines in Australia, Namibia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Tanzania, and Angola. This strategic patience has transformed rare earth dominance into geopolitical leverage.

"The dragon was vigilant enough to recognise the value of these minerals way back when the world was obsessed with Gulf oil," Patil observes. "Thanks to their forethought, they now dominate the market. This diversification and control has greatly aided them in becoming the superpower they are today."

India, meanwhile, sat on its hands.

A watershed moment arrived in 2023 when the Mines & Minerals (Development & Regulation) Act (MMDR) of 1957 was amended to allow private sector participation in the exploration of 29 critical and deep-seated minerals. The introduction of an Exploration Licence represented a philosophical shift, an acknowledgement that government agencies alone could not unlock India's mineral wealth.

Around 20 companies have benefitted from this policy change, with a handful proving particularly instrumental. Patil's own company, GeoExpOre, is presently involved in two rare earth exploration projects funded by the National Mineral Exploration Trust, with encouraging results.

Yet even this progress reveals the grinding reality of mineral exploration in India.

"Generally, exploration is a long drawn-out process," Patil explains. "Earlier, thanks to previous government policies, it would take around 14 to 15 years to monetize a mine—from discovery to production."

Fourteen to fifteen years. An entire generation from finding something to actually using it.

The Grinding Reality of Exploration

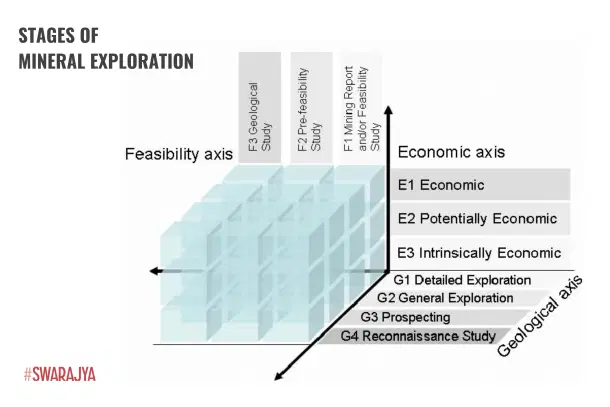

The exploration process unfolds through four stages (G4, G3, G2, and G1) each progressively narrowing the focus and increasing accuracy.

At the G4 stage, reconnaissance surveys use remote sensing and geochemistry to identify potential mineralisation across vast areas, perhaps 600 square kilometres.

By G3, systematic geological mapping and detailed surveys narrow this to 100 square kilometres of concentrated anomaly zones.

G2 stage builds confidence through close-spaced drilling and structural analysis, progressively identifying the geometry, thickness and grade of deposits.

Finally, at G1, dense drilling grids and bulk sampling deliver measured resource estimates.

"Four to five years is taken to reach the G1 stage," Patil notes.

Then the waiting begins.

Once exploration is complete, the report goes to the government (state or central). Then comes the auction process. The timeline for this crucial step? Variable, to put it charitably.

"From the stage of report submission to auction, the government usually takes its own time. Rarely would it occur back to back. Its timeline would usually depend on the official's mood," Patil says, his understatement carrying the weight of experience.

"However, in the last three to four years, the attitude has changed dramatically. Critical minerals are going for auction very quickly. This has helped reduce the time from discovery to mine formation."

But even for the auction winner, the ordeal has only begun. Forest department clearances, environmental approvals, permissions from local panchayats (each represents a potential veto point, a place where bureaucratic lethargy or political opposition can stall progress indefinitely).

"After obtaining the mine lease, the next step is to make a mine plan. This takes about a year. Post this, mineral processing begins. It takes about 18 to 24 months to establish a plant."

This is how entire decades disappear.

"This is how the entire 14 to 15 years gets killed," Patil acknowledges.

Enter Artificial Intelligence

Yet technology may offer what policy has failed to deliver: a dramatic compression of timelines.

"Now with the advent of AI, the entire timeline can be reduced by 60 to 70 per cent," Patil claims.

GeoExpOre's Earthscience.AI represents one of the first companies working specifically on geological data, perhaps the most heterogeneous data type imaginable. A single rock contains multiple formation varieties created over millions of years. Understanding change requires traversing through deep time.

"We spent almost 24 months working with geologists and engineers to combine and harmonize their expertise," Patil explains. "The engineers were used to dealing with very structured data, the kind often found in healthcare and automobile industries. However, geological data has millions of features that are often hard to classify—tectonic changes that occurred millions of years ago, different rock formations, the varied behaviours of minerals, pathfinder minerals, the immense stratigraphy within rocks."

The results suggest this investment paid off. In work for Kazakhstan-based companies and two major Indian firms (protected by NDAs), GeoExpOre identified resources in a greenfield project and pinpointed drilling locations within 14 days, reducing timelines by approximately three years.

"A particular challenge with greenfield projects is that not much work is done in the region, so we're dealing with very limited data," Patil notes. "We began with just two-line geological data provided to us, largely academic interest studies done during British times. We had to collect the data firsthand and then feed it into our AI model, which helps with both cost and time."

The only comparable competitor in this space? KoBold Metals, Bill Gates' company, backed by approximately $100 million in funding.

The Technology Gap

When conversation turns to processing technology for critical minerals like lithium and nickel, Patil's assessment is blunt.

"India has almost zero domestic processing and extraction technology, as we were not focused on these minerals."

The government has recently approved around 1,500 crores for recycling rare earth minerals, a gesture towards self-sufficiency that may prove inadequate.

"If Indian companies and research are funded liberally, India can dominate this space," Patil argues. "As long as we import the technology, we may end up manufacturing magnets here, but there will never be complete technology transfer."

Even handheld XRFs (X-ray fluorescence analysers that provide elemental data and allow field identification of mineral signatures) must be imported. India lacks the technological capability to manufacture these basic exploration tools.

Local Resistance and Political Challenges

Beyond bureaucracy and technology gaps lies a more immediate challenge: local resistance.

"We worked on a nickel project with great prospects, but the project was stalled," Patil recalls. "People and politically motivated entities often pose challenges. Sometimes there's a delay in permissions from the forest department. The Taluka panchayat people get involved."

GeoExpOre's approach involves patient engagement: "We try to reason with the locals, explain that in exploration we do not blast anything. We do minimal drilling with limited environmental impact."

Recently, the central government introduced a new forest policy meant to expedite drilling, with permissions being granted for more number of wider bore holes, a welcome move, though its effectiveness remains to be tested against entrenched opposition.

Drill More, Drill Deeper

The 2023 MMDRA amendments represent progress, but reveal how even well-intentioned reform can entrench existing power structures.

The Exploration Licence allows companies to discover minerals using their own money, with the government covering only 50 per cent of exploration costs. Upon discovery, the deposit goes to auction. The exploration company receives merely a royalty; the ultimate beneficiary is the auction winner.

Here's the trap: companies applying for Exploration Licences must demonstrate a net worth of 25 crores.

"When a company puts all the effort to identify minerals, and at the end of the day it ends up in auction, 25 crores net worth becomes a very tall order," Patil explains. "This restriction essentially makes exploration the monopoly of a few large companies that have the scale and depth. By default, they begin to own these resources."

For a nation that must accelerate exploration activities, this represents a structural impediment disguised as a safeguard.

"Given that India is now at a stage where it has to go full throttle in terms of exploration activities, this is not a good sign," Patil warns.

Another issue that Mr Patil highlights is the need for deeper drilling. "India, under the GSI is doing an excellent job with its airborne geophysical survey. However critical minerals are very deep seated" he says. "private exploration companies are presently allowed to drill up to 100- 150 ms of depth, in comparison China goes as far down as 500-800m. Companies need to be allowed to dig deeper, with greater quantity of wider bore holes" he concludes.

The Geologist's Central Role

Throughout the conversation, one theme emerges repeatedly: the need to place geologists at the centre of the entire value chain.

"Since geology is the core, the mother component of dealing with critical minerals, if geologists are employed right from exploration to mine planning and mineral processing design, it will result in great effectiveness in terms of both cost and time," Patil argues.

This matters particularly when ore characteristics change.

"If there is change in the ore quality, that is change in ore characteristics when it goes to the plant, then the metal quality also changes. Geologists understand this continuity."

The alternative (treating geology as merely the preliminary phase before handing off to engineers and administrators) leads to inefficiencies that compound over time.

Understanding Ore Reality

One common misconception deserves puncturing: the idea that ore bodies consist primarily of the desired mineral.

"While the common perception is that an entire ore of a particular mineral must consist of the mineral, this could not be farther from the truth," Patil notes. "Take one ton of ore from the Hatti gold mines. After processing, we arrive at only about 2.5 to 3 grams of the precious metal."

This reality (that vast amounts of earth must be moved and processed to extract tiny quantities of valuable minerals) underscores both the technical challenge and the environmental considerations that make every inefficiency costly.

The Funding Paradox

Funding, at least in theory, is not the constraint.

The National Mineral Exploration Development Trust has approved a total of 584 projects and has completed 302 of them with a documented spending of Rs 3193cr (most of which has been granted to Mineral Exploration and Consultancy, a government corporation).

The newly formed National Critical Mineral Mission has around 36,000 crores, substantial resources by any measure.

"There is enough money," Patil confirms. "Rather than having a small drilling presence, if private exploration companies are granted approvals and funding we can bring in newer and more innovative technology."

Yet India has not been aggressive in drilling, preferring to maintain tight government control even as tens of thousands of crores sit waiting for productive deployment.

The pattern repeats: resources available, regulatory frameworks restrictive, timelines extended, opportunities missed.

The Success Rate Reality

For those imagining that every exploration effort strikes gold, Patil offers a sobering statistic.

"For every 10 investigations, presently 25 to 30 per cent turn out to be economical."

This hit rate (roughly one in four) makes the case for aggressive, widespread exploration rather than cautious, limited efforts. The only way to find economical deposits is to look in many places. The only way to accelerate discovery is to let more entities look.

On an encouraging note the government is supportive of exploration of critical minerals in the north eastern states with the NMEDT offering private companies both additional funds and incentives.

Moreover, the government has established Khanij Bidesh India Limited (KABIL) with the mandate to identify, explore, acquire, develop, mine, process, procure strategic minerals outside India for supplying primarily to India.

The Path Forward

As the conversation concludes, Patil's prescription is straightforward.

"More drilling and more AI should be our mantra."

The geological potential exists. The technological tools are emerging. The funding sits available. Even the policy framework has improved marginally.

What remains absent is a greater vision to truly unleash exploration, to achieve self-reliance and to accept that speed matters, that monopolistic structures serve no one, that 25 crore net worth requirements protect incumbents rather than ensure quality.

India's critical minerals remain critical in more ways than one. Critical for the economy, critical for national security, critical for the clean energy transition, and critically, urgently, frustratingly out of reach despite being literally beneath our feet.

The question is no longer whether India has minerals. The question is whether India has the courage to let them be found.

Adithi Gurkar is a staff writer at Swarajya. She is a lawyer with an interest in the intersection of law, politics, and public policy.