Bihar

Bihar After Nitish: BJP’s Expansion, JD(U)’s Erosion, And Smaller Parties Fighting For Survival

Abhishek Kumar

Oct 21, 2025, 11:33 AM | Updated 01:47 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

For two decades, every election in Bihar began and ended with Nitish Kumar. The parties, the alliances, the caste arithmetic – they all revolved around him. In 2025, Kumar's dominance has paved the way for his swansong, owing to health concerns.

With Kumar gradually receding from the frontlines, the vacuum left by a leader who once dictated the pace, direction and outcome of Bihar politics is closer than ever.

This has triggered a three-way scramble for dominance. The BJP is positioning itself to fill the space, JD(U) is fighting to hold its traditional vote banks, and smaller parties are desperate to increase their share. The outcome will determine not just who governs Bihar, but whether the NDA retains cohesion or fractures under the pressures of caste, leadership ambition and electoral arithmetic.

This has set the stage for an election defined not by one towering figure, but by a constellation of competing actors.

Horse One: The BJP's Calculated Expansion

While JD(U) struggles to retain its base, the BJP is manoeuvring to occupy that very space. Observing the BJP's history of gradually expanding its share in alliances and eventually engulfing its partners, many believe the party will do the same with JD(U).

In 2025's NDA seat-sharing, BJP and JD(U) will each contest 101 seats out of the total 243. That level of dominance, however, comes with unprecedented responsibilities.

The Kushwaha Strategy

The BJP's most visible gambit centres on Samrat Chaudhary, a Kushwaha who is being projected as a potential chief ministerial face, keeping the community's hopes alive within the NDA fold.

To understand why this matters: Kushwahas comprise 4.21 per cent of Bihar's population, while Kurmis are 2.87 per cent. Although Nitish Kumar has generally refrained from aligning himself with any particular community, Kurmis and Kushwahas, the Luv-Kush duo, have historically rallied behind him since the 1994 Kurmi Ekta rally, where Kumar expressed his dissatisfaction with Lalu Prasad Yadav's preference for Yadavs at the top of the OBC hierarchy.

While Kumar himself belongs to the Kurmi community, there was a tacit understanding that a Kushwaha leader would be given priority after him. This makes the Kushwaha vote crucial for whoever wants to inherit Kumar's coalition.

By fielding Chaudhary as an MLA candidate from Tarapur, his father's old seat, the BJP is signalling its intent to capture this vote bank. Even if Chaudhary's administrative reputation does not match Kumar's, the party can still secure Kushwaha voters by offering him unconditional support against Prashant Kishor's onslaught.

But there is a problem. Prashant Kishor has damaged Samrat Chaudhary's image through persistent press conferences, which could dampen Chaudhary's prospects, especially given that the traditional BJP cadre in Bihar dislikes outsiders and still remembers that Chaudhary's father once threatened to kill Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

This creates an opening for Plan B. Upendra Kushwaha, the national president of the Rashtriya Lok Morcha (RLM), is another senior leader from the community and a strong contender for that vote bank. He enjoys a reputation similar to Nitish Kumar's – honest, cadre-oriented, educated, clean and pro-Bihari.

Kushwaha is known for his careful blend of flexibility and principle. Like Nitish, he has shown courage during the downward spirals of political life, which has helped him earn the trust of the BJP's top brass. This trust translates into a distant but possible scenario where he might merge his party and emerge as the community face of the BJP.

It is a far-sighted projection, but two factors give it traction. Firstly, Kishor's attacks on Samrat Chaudhary. Secondly, the BJP has a history of last-minute, out-of-the-box manoeuvres, often picking candidates who were not even in the experts' shortlist.

But caste arithmetic alone will not secure dominance. To translate social support into votes, the BJP also needs to recalibrate its relationship with Bihar’s largest voter bloc, the EBCs.

The EBC Challenge

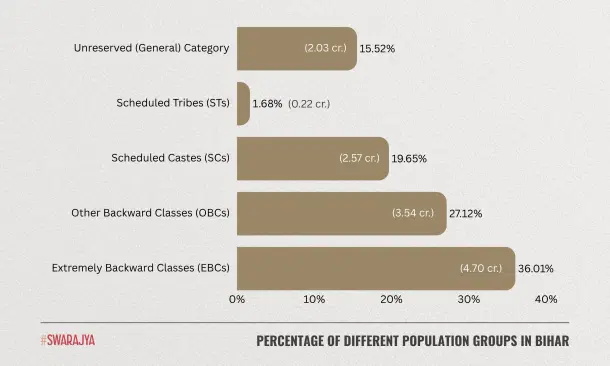

The BJP's second challenge will be maintaining support among Extremely Backward Classes (EBC) voters, who comprise nearly 36 per cent of Bihar's population. Except for central government schemes, the state unit has done little to establish itself among EBC voters.

Apart from Kumar, Prime Minister Narendra Modi remains a popular name, but both leaders' welfare schemes are nearing the expiry of their political utility. This makes the task of retaining voter loyalty more difficult.

While projecting a new face, the BJP must simultaneously recalibrate its outreach to EBC voters to consolidate its growing presence. One effective strategy could be using its extensive cadre network to promote central government schemes as targeted benefits for particular communities.

For instance, when a decision is announced for the welfare of defence personnel, the message is framed as benefiting the Jat community. Similarly, material benefits accruing from government schemes can be presented as pro-EBC by citing deficiency data from the caste survey.

As for an EBC face, the BJP currently has Hari Sahni, who has done reasonably well, though his appeal remains limited. This raises the possibility of the BJP encouraging Mukesh Sahani's party to merge with it. Sahani himself is aiming for a Deputy Chief Ministerial position, projecting himself as the "son of EBCs", a more inclusive identity than the "son of Mallah".

The Infiltration Factor

Several senior JD(U) members, including current working president Sanjay Jha, a protégé of Arun Jaitley, are often accused of being "BJP men" within JD(U). Only time will tell whether this strategy succeeds, but trends suggest the BJP will soon eclipse JD(U) in the alliance.

Horse Two: JD(U)'s Struggle for Survival

JD(U) faces twin existential crises: losing its traditional vote banks and an impending leadership vacuum that could tear the party apart.

The Kushwaha Problem

Since 2015, Kumar's relationship with the Kushwahas has been uneasy. Their growing disenchantment contributed to the Janata Dal (United) [JD(U)] being restricted to 43 seats in the 2020 Assembly elections. In 2020, JD(U) won only 43 seats in the 243-member Bihar Assembly.

In the last two election cycles, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) has actively targeted the Kushwahas as a distinct voting bloc, with considerable success in the 2024 General Elections. On the other hand, the BJP has projected Samrat Chaudhary as a potential chief ministerial face, keeping the community's hopes alive within the NDA fold.

In any case, JD(U) is likely to face a vacuum when it comes to its hold over the Kushwaha vote.

The EBC Erosion

The same holds true for the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs), who comprise nearly 36 per cent of Bihar's population and have been another stronghold for Kumar.

EBC voters need a face with a pan-Bihar appeal. Among the current crop of leaders, only Mukesh Sahani seems to be preparing to fill this void. He now prefers to call himself the "EBCs' prodigy" rather than the "Son of Mallah", a title that confined him to one EBC caste group, the Nishads.

The Internal Leadership Crisis

Apart from caste arithmetic, JD(U) also faces an impending leadership crisis. Although the party identifies as a representative of backward communities, two upper-caste leaders, Union Minister Lallan Singh and national working president Sanjay Jha, are said to dominate decision-making, aided by Samrat and Vijay Chaudhary.

JD(U)'s original cadre is reportedly opposing this dominance, especially because three of these four leaders come from upper-caste backgrounds, while JD(U) owes its existence to empowering the backward classes.

The internal bickering has already led to the ousting of several educated and high-performing leaders in recent years. Kumar has managed to hold the party together, but experts believe he has not prepared anyone to replace him, a vacuum that could soon spark a leadership clash.

Without the Kushwahas, with EBCs drifting, and with internal factionalism rising, JD(U) faces the prospect of collapsing from both external pressure and internal contradictions.

Horse Three: Smaller Parties' Survival Gambits

The power vacuum has put smaller NDA allies in precarious positions and presented unexpected opportunities for those who can read the moment.

Chirag Paswan's Ascent

Currently, Chirag Paswan's Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas) [LJP(RV)] is seen as the largest protectorate of Dalit voters in Bihar. For Paswan, Kumar's exit would mean greater bargaining power within the coalition and a thaw in his strained relationship with JD(U).

The perennial talk of LJP(RV)'s merger with the BJP could also resurface, but such a deal would come at a price. Paswan is unlikely to settle for anything less than a Chief Ministerial position.

Jitan Ram Manjhi's Dilemma

While JD(U) and the BJP are expected to undergo significant transformations, Kumar's eventual departure could have serious consequences for Jitan Ram Manjhi and his Hindustani Awam Morcha (HAM).

Within the NDA, Manjhi has long enjoyed Kumar's patronage. In his absence, his bargaining power could decline sharply unless the party reinvents itself from being an NDA-dependent ally to an independent Dalit force. That could position it as the state's second-most influential Dalit party.

Mukesh Sahani's Repositioning

Mukesh Sahani represents the wildcards, leaders without Kumar's protective umbrella but with expanding ambitions. By rebranding from "Son of Mallah", which confined him to one EBC caste group, the Nishads, to "EBCs' prodigy", Sahani is positioning himself as the pan-EBC face that both BJP and JD(U) lack.

His next move, staying independent, merging with BJP for a Deputy CM position, or playing kingmaker, could determine which of the larger horses wins the race.

The Convergence: Who Inherits the Luv-Kush Coalition?

All three narratives converge on the same prize. The coalition that can successfully reorganise Kumar's voting arithmetic, Kurmis (2.87 per cent), Kushwahas (4.21 per cent) and EBCs (36 per cent), while maintaining upper-caste and Dalit support, will dominate Bihar politics for the next decade.

The BJP has resources, organisation, momentum and a plan to absorb JD(U)'s vote banks piece by piece. It has two potential Kushwaha faces, strategies to reframe welfare schemes as EBC-targeted, and alleged infiltrators within JD(U) itself.

JD(U) has institutional memory, residual loyalty and the benefit of being Kumar's party, but it is haemorrhaging votes, facing a leadership crisis between upper-caste leaders and backward-class cadres, and has no clear successor to Kumar who commands statewide respect.

The smaller parties have niche vote banks that could prove decisive in a fragmented field. Paswan controls Dalit votes and wants the top job. Manjhi must choose between continued subservience or risky independence. Sahani holds the key to EBC consolidation and knows it.

The Verdict

The 2025 Bihar Assembly election is set to be unlike any in recent memory. Nitish Kumar's gradual withdrawal removes the stabilising centre, leaving a competitive arena in which all of the emerging actors are calculating, repositioning and testing the boundaries of influence.

The disturbance of equilibrium will determine whether the NDA retains cohesion or fractures. For the first time in two decades, the election is not about one towering figure, but about three parallel races, each with its own logic, each with its own endgame.

The BJP races to consolidate and absorb. JD(U) races to survive and reinvent. The smaller parties race to maximise leverage before the dust settles.

The winner will inherit not just power, but the template for coalition politics in India's most fragmented political landscape. And unlike previous elections, no one, not even the contestants, can confidently predict which horse will cross the finish line first.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.