Economy

Beyond Wages: Why There's A Need To ‘Skillify’ MGNREGA

Mohini

Oct 14, 2025, 04:21 PM | Updated 04:21 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

MGNREGA, once hailed as a “stellar example of rural development”, was conceived to provide at least 100 days of guaranteed wage labour for unskilled manual work to willing adult members of rural households, thus promising the fulfilment of the ‘right to work’ under Article 41 of the Indian Constitution for rural communities.

However, after two decades of its enactment, the Act and its income-oriented approach appear increasingly out of step with the systemic shift towards entrepreneurship, upskilling, and capability-based pathways.

Structural Limitations: A Scheme Out of Step with Changing Times

The major issue with the Act, by its very design, is that it relies on “unskilled manual labour”. This stands in stark contrast to the current focus on Skill India. The Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE)’s Vision Statement for 2025 aims to “unlock human capital to trigger a productivity dividend and bring aspirational employment and entrepreneurship pathways to all.”

In a country progressing steadily towards becoming the third-largest global economy, the inability to harness the “human capital” of about 63 per cent of the population can be highly detrimental to its skilled economy.

Furthermore, MGNREGA, viewed through a welfarist lens, treats people primarily as beneficiaries of government action, limiting their role to passive recipients who work as and where the state directs. This curtails the diversity of work potential that individuals can offer and restricts opportunities for meaningful socio-economic mobility, depriving them of the chance to develop their capabilities.

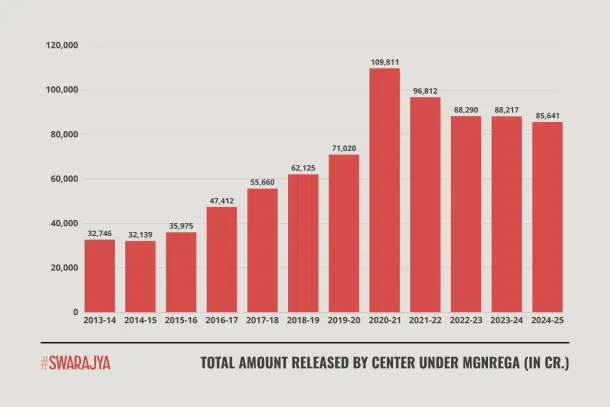

With government budgeting increasingly prioritising entrepreneurial and skill-based programmes, MGNREGA has experienced budget cuts, registering a 23.78 per cent drop in allocation from FY 2020-21 to 2024-25. The scheme has struggled to compete with productivity-boosting programmes such as the Skill India Programme (SIP) and Employment-Linked Incentives (ELI).

This has diluted the effectiveness of the Act and its intended purpose.

A 2022 report by the Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj, chaired by Mr Prataprao Jadhav, highlighted numerous flaws in MGNREGA, including wide state-wise disparities in wage rates, non-payment of unemployment allowances, and delays in payments beyond the stipulated 15-day period, drawing attention to the declining impact of a once-revolutionary Act.

Hit-and-Trials at ‘Skillifying’ MGNREGA

The need to attach a skill-based element to MGNREGA is not a new demand.

In 2015, Project LIFE (Livelihood in Full Employment) was launched as a convergence project between MGNREGA, the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM), and the skill division of the Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD) to upskill about 3,69,802 people by 2020 who had completed 100 days of MGNREGA work.

However, MGNREGA’s 2023 Director, Mr Dharmvir Jha, noted that it achieved barely a 50 per cent success rate, primarily due to the lack of compensation for wage loss during training, forcing participants to stick to unskilled work for assured wages.

Learning from LIFE’s shortcomings, the Government of India launched Project UNNATI in December 2019. This skilling project under MGNREGA aimed to enhance employability for individuals completing 100 days of MGNREGA work in the previous financial year through:

a) wage employment via Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY) for people aged 18-35 years;

b) self-employment via the Rural Self Employment Training Institute (RSETI) and Krishi Vigyaan Kendra (KVK) for those aged 18-45 years.

Initially planned for three years until March 2023, the project has been extended twice, first to March 2025 and then to March 2026. It has struggled to meet its target of training 2,00,000 beneficiaries, achieving only 90,894 individuals as of March 2025.

While multiple factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic and coordination challenges between states and the Centre, contributed to this shortfall, the intended benefits of the scheme have not fully reached rural communities.

Policy Recommendations: Charting the Road Ahead

The intent to revamp MGNREGA is clear and commendable. It is now essential to convert this intent into structured outcomes. Rather than continuing extensions, a detailed, phase-wise plan should be developed, beginning with pilot testing at district levels where demand for unskilled labour is relatively low. This would ensure that skilling interventions do not compromise the livelihood purpose of MGNREGA.

Each district could prepare its own skill development plan, similar to district-level plans for irrigation or agriculture under other flagship rural schemes. Localised plans would make training relevant to local economies, such as pisciculture in coastal belts, solar panel installation in Rajasthan, or bamboo craft in the North-East.

This plan could operate as a 2.0 version of Project UNNATI or as a new rural empowerment initiative under MGNREGA. The starting point could be a structural change, offering rural participants a choice between 100 days of unskilled work or 100 days of skill training with an adequate compensatory stipend.

Given the scale and potential impact, such a scheme should be multi-ministry. The Ministry of Rural Development may act as the nodal body, while other ministries, such as the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology for digital literacy and agri-tech, the Ministry of Textiles for craft-based training, and the Ministry of Fisheries for aquaculture, could contribute sectoral modules.

Integration with existing infrastructure, such as Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), polytechnics, Krishi Vigyan Kendras, and MSME clusters, would avoid duplication, save resources, and connect beneficiaries with local technical hubs.

An attempt has already been made to integrate the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship’s PM Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PM-KVY) for youth and the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises’ PM-Vishwakarma Yojana for artisans under the one-year extension of Project UNNATI. It is important that these initiatives continue beyond March 2026 and are incorporated into future skilling programmes under MGNREGA.

For skills to translate into livelihoods, market integration and certification must be prioritised. Beneficiaries could receive certification from the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) or relevant Sector Skill Councils to enhance mobility in the labour market.

Skilling should be backed by linkages with Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), cooperatives, and government procurement channels. Artisans and self-help groups could be connected with e-commerce networks such as the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC).

The requirement of 100-day work experience under MGNREGA for eligibility in skilling courses, as present in Project UNNATI, should be removed. The average days of employment per household in MGNREGA was around 43 days in 2024-25, with a maximum of 52 days since 2012-13, creating a barrier to accessing training opportunities.

Special attention should be given to gender-minorities and marginalised groups. Women’s participation requires gender-sensitive measures, such as crèche facilities at training centres and inclusion of courses like tailoring, food processing, or online micro-work, without excluding them from traditionally male-dominated trades.

Courses for particularly vulnerable tribal groups could focus on value addition in non-timber forest produce or ecotourism, combining ecological preservation with economic empowerment.

Financing this shift requires fiscal realism. Instead of new allocations, a share of the annual MGNREGA budget, for instance 10 per cent, could be earmarked for skill-building. Public-private partnerships and CSR contributions could support advanced training areas such as digital literacy and renewable energy.

Conclusion

The dream envisioned two decades ago is not entirely lost. Changing times call for adjustments in almost every aspect of life, and MGNREGA is no exception. It must be reimagined to fulfil its mission of rural empowerment.

As Gandhi notes in Young India (1929), “We are the inheritors of a rural civilisation.” The onus lies on us to honour this inheritance by turning the rural population towards the vision of skilled, self-sufficient, and hi-tech Indian villages.