Economy

The Economics Nobel 2025: Lessons In Creative Destruction And Innovation That India Cannot Ignore

Samridh Joshi

Oct 19, 2025, 07:30 AM | Updated 09:27 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2025 was awarded on 13 October to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.

While Mokyr received recognition for his work on identifying the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress, Aghion and Howitt received the same for modelling the theory of creative destruction and taking forward the work of famed political economist Joseph Schumpeter notably his very popular book, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy published in 1942.

This year the prize recognised the fact that innovation is a critical endogenous element of economic growth and has been one of the key defining factors for economic development in the modern era. In the context of the Indian economic and political landscape this fact offers significant lessons for the future.

Knowledge, Practice and New Normals

While growth through innovation is seen as default in today's world, it was not the case historically. Mokyr brought to light the fact that throughout the post-renaissance era, growth from the 14th to 17th century stagnated while innovations accelerated.

This is due to three major factors, lack of continuous chain of evolution in new ideas or what Mokyr calls useful knowledge, little practice from theory and resistance to change. Discoveries and subsequent inventions on the ideas happened in short bursts of time and were mostly disconnected, leading to stagnation.

The industrial revolution marked the growth in micro inventions or incremental innovations grown over macro or major innovations, creating knowledge for growth. For instance, while the invention of semiconductors is a macro invention, it is the innovations in chipsets and computational devices that brought out the IT revolution and associated growth.

It is this synergy that differentiates renaissance era from the industrial revolution. While the former was marked by groundbreaking inventions, growth only took off with the industrial revolution when micro inventions built over the breakthroughs.

In other words, the industrial revolution marked the synergy between 'propositional knowledge' or knowledge about how the world worked and 'prescriptive knowledge' or why it worked as so, creating useful knowledge for innovations.

If we look at the present day scenario of the Indian economy, most corporations as well as individual entrepreneurs are stuck in the zone of what Mokyr calls 'mechanical competence', where agents are skilled in carrying out instructions derived from prescriptive knowledge.

While this is critical for growth, what is lacking are 'skilled practitioners', the individuals who possess sufficient know-how in accessing new knowledge, which they can put to practical use by a little bit of tinkering and tweaking.

To create such a pool of talent, there needs to be significant investment in upskilling, quality education and a significant uptick in important R&D fields which is currently a meagre 0.65% of the Indian GDP.

In addition to the aforementioned requirements, as a society, India needs to be open to change. Just as the Enlightenment marked a new era of acceptance of ideas and change, Indian society must be ready to accept radical transformations while keeping its socio-cultural ethos alive.

Competition watchdogs need to ensure that space for new players to innovate is kept free from assault by corporations besides encouraging startup ecosystems to prosper.

Creative Destruction

The work of Aghion and Howitt is responsible for creating a mathematical model of creative destruction by bridging the gap between microeconomic interactions, industrial organisation and macroeconomic growth.

Joseph Schumpeter posited the idea of creative destruction in economics where new firms and innovations drive out old production and ideas. However as intuitive as it may seem, a model making innovation endogenous to the general equilibrium of the economy eluded for nearly half a century when Aghion and Howitt (1942) created the modern workhorse for the economics of innovation.

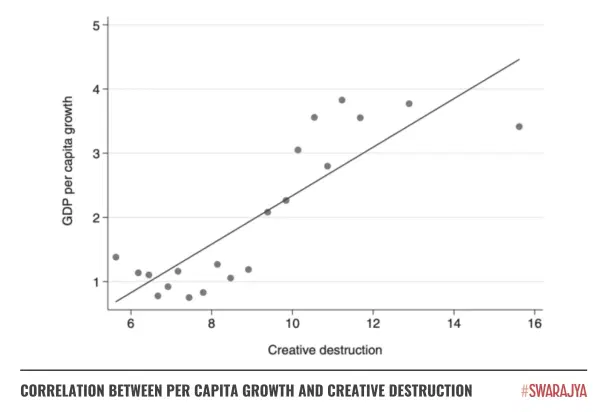

Economic research attributes more than a quarter of the average growth in total factor productivity to 'entry and exit of firms' or creative destruction while the remaining is due to continuing production.

There are estimates that show that almost half of the total factor productivity growth in the US from 1997-2015 was due to reallocation of production factors from low to high revenue productivity firms. There is a clear positive correlation between the growth of per capita GDP and rate of creative destruction.

For firms, the probability of a successful innovation, though influenced by R&D investment, is still uncertain. This implies that incumbent firms try to block entry of new entrants in the market. Thus large, incumbent players have vested interests in lobbying for restrictive policies.

This situation is all too familiar with Indians from the License Raj era where mega corporate houses actively supported a closed economy where their influence could subdue any new competitor.

Keeping the effects of that approach in mind, Indian policymakers should remain wary of such efforts at this critical juncture of India's growth story and push for a fair space for new innovators and incumbents alike.

Competition and Optimal Policies

Competition breeds innovation. Aghion showed that when competition is neck-to-neck, firms have high incentives to innovate. For firms that lag far behind, incentive to innovate withers and the firms may even lose market and collapse, eclipsed by the innovation of a new competitor.

A classic example is one of Kodak, a name once synonymous with photography failed to innovate into the age of digital photography and eventually had to file for bankruptcy. While in certain cases, state support can help keep such firms buoyant such moves are not appreciable unless sufficient innovation is pushed through, as seen with BSNL.

The general relation between competition and innovation is U shaped. At the higher end of the spectrum, excess competition can increase uncertainties to such levels that innovation may become too expensive to sustain while at the lower end, monopolists dominate and won't bother to innovate.

Innovation responds to policies and incentives as it is a social process. Hence the optimal policies would be to support a middle ground. Indian policymakers must remember this interlinkage and pay heed to similar research while designing policies influencing R&D investment decisions.

Crisis Management

Innovation creates both winners and losers. In high growth scenarios and frontier innovations, old firms and practices may begin to lose relevance and potential increase in unemployment may follow.

Such a threat looms heavily in the present with the advent of the AI led Fourth Industrial Revolution, especially for nations like India which are heavily dependent on outsourcing and mechanical competence rather than leading frontier innovations in the technical sphere.

It is very crucial for India to be prepared for managing such a crisis besides supporting those affected. To help in this future predicament the following systems can be of help:

a. Flexicurity: A labour market model combining flexibility for employers (easier hiring and firing) with security for workers through comprehensive unemployment benefits and active job finding support.

b. Social support programmes include classic proposals for UBI and securing essentials such as housing, food and healthcare for the ones undergoing a phase of unemployment due to creative destruction. Generous unemployment benefits cushion subjective well being from rates of job destruction.

Creative destruction also entails concerns about energy transition, ecology and environment. For instance data centre requirements for AI compute needs massive supply of water and may hit local ecologies.

Finite natural resources play a hindrance in the models of creative destruction. Sustained growth is not the same as sustainable growth and the negative externalities arising should have some space to dissipate.

Systems for India

It is observed in studies that the size of industrial plants grows more strongly with age in the United States than in India. This is indicative of the fact that the American financial system selects firms with the highest growth potential while India shows the exact contrarian perspective with labour laws and financial systems disincentivising scale and creating perverse incentives.

On this front, course correction and a middle path are long overdue.

Institutions play an equally important role. Countries like India had adopted policies conducive to growth by accumulation of capital including import substitution but failed to create institutional systems that were adapted to transition to innovation economies.

Although major progress has been made on this front under the Modi Government, yet much is left to be desired.

Another systemic area of focus has to be education and technology transfers. For instance, China has far higher average educational attainment than comparable countries like Brazil and India. 78.6 per cent of the Chinese population had completed secondary education by the age of 25 as against only 51.6% for India as of 2018.

Chinese policies promoted FDIs. A combination of these two facts led to China gaining access to cutting edge western technologies and it has now graduated to self innovation. India needs similar synergistic strategies and systems for innovation led growth.

Industrial plant level productivity is heavily dispersed in India with the fraction of plants having low productivity being far greater than the US. This inability of Indian plants to grow beyond scales leads to less innovation in aggregate and hence less productivity growth for the economy as a whole.

One possible reason suggested by Aghion is due to nepotistic family management and managerial incompetence or imperfect credit markets. Managerial systems and skillsets need to be nurtured with expansion of IIMs and similar institutions.

Limiting executive power is essential for an 'innovation economy'. On this issue, though the Indian executive has been satisfactory, the judiciary at times have gone overboard through judicial activism taking a dangerous turn wherein it threatens the same structures it was meant to protect.

Restoring the fine balance along with re-establishing their roles as neutral arbitrators and watchdogs of competition space rather than taking sides itself becomes critical for Indian judicial and executive systems today.

To summarise the Nobel in one statement would be to say, 'growth in the modern era is determined heavily by innovation and creative destruction'. While nations like China have caught up with this reality, India cannot possibly afford to be left out of this paradigm.

Samridh Joshi is an Economist and Public Policy Consultant. He is an alumnus of IIT Kanpur and UC3M Madrid. Views are personal.