Books

Hindu Civilisation: Pavan Varma Takes On Amartya, Romila, Wendy In New Book

R Jagannathan

Sep 16, 2021, 09:57 AM | Updated 09:56 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

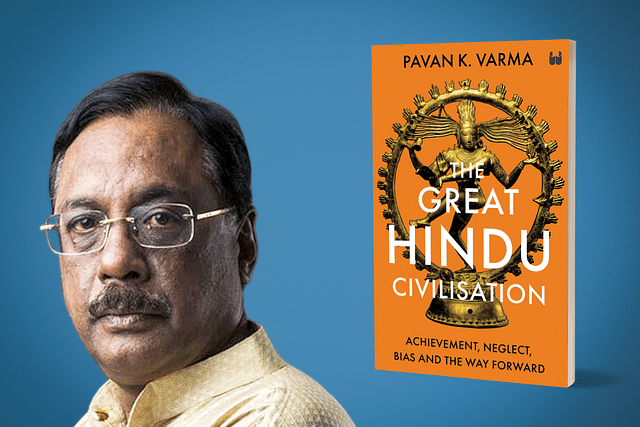

The Great Hindu Civilisation: Achievement, Neglect, Bias and The Way Forward. Pavan Varma. Westland. 2021. Rs 799. Pages 403.

In these days where it is impossible to have a decent conversation between Right and Left in India, where there is no middle ground between seeing 'Hindutva' as evil and asserting the legitimate rights of Hindus to own narratives and sense of heritage, Pavan Varma’s book on The Great Hindu Civilisation comes as refreshing riposte to both camps. The former more than the latter.

Of course, the Left-liberal caucus may 'cancel' Varma for his positive views on the past while acknowledging Hinduism’s obvious flaws and biases, and the lumpen Hindu fringe may hate his anti-Hindutva tirades, but the middle ground that Varma explores in the book is vital for all Hindus to understand in order to have a sensible conversation around our past, present and future. (View my interview with the author here)

Varma, is a public figure and intellectual, having been a part of the Janata Dal (United) in Bihar and a foreign service diplomat. He speaks with deep knowledge and reverence for Hindu heritage. He has written books on Adi Shankaracharya (Hinduism’s Greatest Thinker), Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas (The Greatest Ode to Lord Ram), and The Book of Krishna, among others, underlining the fact that he is no deracinated Hindu excoriating the violent parts of political Hindutva. This is in contrast to those Hindus who are more political than Hindu, and this probably includes Shashi Tharoor who discovered that he was Hindu only after he decided that Hindutva needs to be attacked politically.

The high notes of Varma’s book are in the first five chapters, which discuss the cerebral core of Hindu civilisation, the audacity of thought and ideas explored in it, the impact of Islam’s depredations, and the damage done to the Hindu psyche by colonial interventions. The last chapter, which talks of the challenges of the modern republic, however, fails to go beyond the rhetorical claim that acknowledgement of the past should not impact how Hindus should deal with the present, especially when neither Christianity nor Islam have given up their negative views on Hinduism and believe that conversion has to be achieved by hook or by crook.

Also, if few among India’s left-liberal elite are willing to accept what Varma has to say about Hinduism’s heritage from the past, is it only upto Hindus to move on in the hope that its detractors will somehow move along with it? Is true reconciliation between communities possible without all parties acknowledging what was done to Hindus and Hinduism in the past?

The first chapter, which debunks the claims of Western and Leftist historians that Hinduism was a creation of the colonial era and not something that existed from antiquity, is notable for Varma’s strong demolition of liberal doyens, from Amartya Sen to Romila Thapar, from Wendy Doniger to even Jawaharlal Nehru, who thought Hinduism is a relic from the dead past and needed to be de-emphasised so that modernity can be brought in.

Varma trashes historian Sanjay Subramanyam, who happens to be a brother of India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, for his “unhistorical” and arrogant generalisation that to talk of a Hindu civilisation “is the same as the notion of a closed India.”

So, any pride in heritage means the country is closed to modernity or inclusivity, when the very basis of Hindu civilisation is pluralism and a wider acceptance of difference and diversity. Equally arrogant was Wendy Doniger’s statement when she was told that many Indians objected to her depiction of Hinduism. She said she did not think Hindus would read it, and her books were meant for a Western audience. That is Orientalism in spades.

Varma is willing to grant good intentions to some of those who believe that any acknowledgement of a great civilisation may make Hindus demand retributive justice in the present and also float imaginary theories of superiority. Some Hindus certainly have rosy imaginations about what this civilisation achieved in the past (airplanes, plastic surgery, etc) and must be called out, but one wonders whether one can grant noble motivations to an Amartya Sen who called Panini, the fourth century Sanskrit grammarian, an Afghan, when Afghanistan as we know it today did not exist at that time. We might as well attribute the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddha by the Taliban to Panini’s legacy rather than intolerant Islamism.

The second and third chapters deal with the high thinking that characterised ancient India, from the Vedas to the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads, not to speak of Puranas and Dharmashastras. He writes: “The Hindu civilisation was founded, first and foremost, on the audacity of thought”, and this was one reason why even as dissent and divergence emerged, it remained strong while other civilisations, like those of Egypt, Greece, South America and Africa, perished.

On the downside, Varma suggests that the caste system “acquired its oppressive features around the first century CE, when the Dharmashastras were misused by vested interests to enforce and iron-cast hierarchy.”

The fourth and fifth chapters deal with the damage done to the Hindu psyche with the Islamic conquests and colonial spread, with the former damaging the continuous chain of Hindu evolution by destroying temples and forcible conversions. During the British period, Macaulayisation achieved something even worse: it damaged Hindus’ self-esteem by making them believe that their religion and culture were abominations.

This strain of thought connects everyone from Marx to Macaulay, from Islam to Christianity, and got embedded in the average Hindu psyche through English education and the co-option of educated Hindus into the colonial administration.

The tragedy, according to Varma, is that colonial attitudes were not debunked post-independence, especially by its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. He has greater respect for Mahatma Gandhi, who was rooted in Hindu culture, than Nehru, who could not care less for the culture he was born in. But he is critical of Gandhi for backing bad ideas like the Khilafat movement and failing to call out the Moplahs for unleashing violence and conversion on hapless Hindus in Malabar in the 1920s.

Modern-day appeasement politics can be traced to Nehru’s deracinated approach to Hindu heritage and Gandhi’s unwillingness to hold the mirror to violent Islamism in the hope of building an elusive Hindu-Muslim unity. For a man who put truth on such a pedestal, Gandhi did not quite acknowledge the truth behind some of the violence unleashed by Islamists in pre-independence India.

Varma writes about the impact of colonial rule on Indian mindsets: “Hindus — along with all Indians — were made to feel inferior not only with regard to their religion but also their civilisation, and the relentless critique created a co-opted elite that was — true to Macaulay’s prophetic vision —an accomplice in amplifying this message.”

Varma, who has no love lost for the BJP or its Sangh affiliates, believes that some of these elements are taking India to a Wahhabised version of Hinduism, with intolerance becoming the norm. While there is no denying that some Hindu elements are indeed violent and must be reined in, this is too big a generalisation given that Varma takes the lynchmobs and extreme elements among Hindus as the defining nature of political Hindutva.

He is right to suggest that the BJP may have used Hindu grievances to construct a political platform that gave them victory, but it is far from clear that political Hinduism — which is what Hindutva is partly about — is somehow wrong when political Islam or political Dalitism is taken as acceptable or given quiet acceptance, even respectability. For every lynchmob that killed a Muslim for carrying beef or transporting cows, there is an equal number of gau rakshaks or other Hindus being killed by Islamist elements. Varma skips this need for balance.

But this is minor carping. Varma is entitled to his political views, including opposition to the BJP and the Sangh, as long as he does not believe that Hindus must take everything lying down. This is otherwise a great book, and required reading for all Hindus, whether you are in the Left or the Right of the spectrum.

The first five chapters are for those who want to dismantle Hinduism in the name of dismantling Hindutva, and the last one is for Hindus who know little about their heritage but still want to imagine it as something pristine and without blemish. They want Hindutva without the audacity of thought. Varma has done a great job.

(Here is a link to my Swarajya video interview with Pavan Varma)

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Jagannathan is Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.