Culture

Where 22 January 2024 Stands In Global History

Harsh Gupta Madhusudan

Jan 12, 2024, 03:47 PM | Updated Apr 17, 2024, 05:52 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

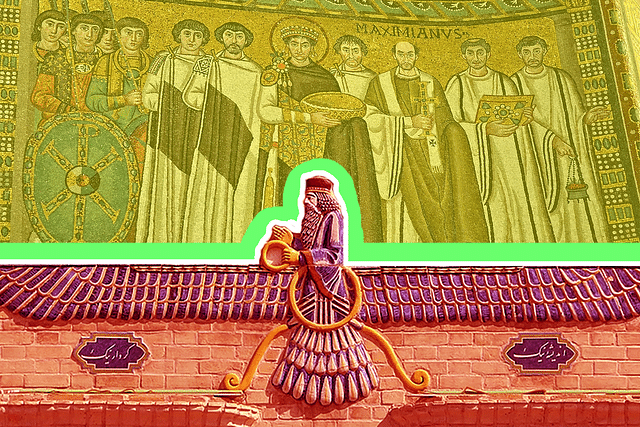

When Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan converted the Hagia Sophia to a mosque again, ending the 85-year Kemalist interim of it being a museum, talk was of its deep symbolism and implications for Christian-Islamic ties. After all, till almost 600 years ago there stood a grand church — Megale Ekklesia initially — which was conquered and converted but then in 1935 conceded by Kemal Ataturk to a neutral territory, as it were.

Some people compared this neo-Ottoman Islamic revivalism and revanchism in 2020 to the Hindutva Ram Mandir movement, where the Hindus won their case in the highest Indian court just a few months earlier, of reclaiming a sacred temple which was destroyed centuries ago to build a mosque with the express intent of humiliating Hindu civilisation.

The analogies flowed fast and thick — Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Erdogan as populist bigots obsessed with history, while Jawaharlal Nehru and Ataturk as rational and forward-looking modernists.

Not litigating that inaccurate description of the four leaders for now, and even ignoring that some in India were OK with Hagia Sophia being a mosque again but not with the Ram Mandir being built in Ayodhya, there is still a key point being missed here.

The Hagia Sophia church was itself constructed in the spot of a pagan temple sixteen to seventeen centuries ago. Specifics are thin in this case, but given the broader recorded history of monotheistic iconoclasm, chances are that the temple itself was destroyed by fanatics in then-Constantinople (now-Istanbul).

Constantine himself, while proceeding somewhat gingerly to begin with, partook in iconoclasm — he destroyed the temple of Aphrodite in now-Lebanon. But often the temple need not be destroyed by the late Roman Empire, so long as the Idol of the Deity was removed, the building or at least parts of it could be reused as a church or for other purposes.

In any case, their aims were achieved by regulations against “falsehood” enforced by the now-converted Roman army and the extra-judicial violence of the “black robed tribe”. The movie Agora dramatises well the fall of classical Alexandria and the murder of Hypatia (a female philosopher-mathematician) in now-Egypt.

One can see this story play out across the world — only the labels changed. Islam represented a purer form of monotheism with its seal of prophecy than Christianity with its Holy Trinity. But the unbelievers suffered all the same.

The writer Gore Vidal once said rather provocatively: “I regard monotheism as the greatest disaster ever to befall the human race… good people, yes, but any religion based on a single, well, frenzied and virulent god, is not as useful to the human race as, say, Confucianism, which is not a religion but an ethical and educational system.”

Yet I do not fully agree with Vidal, though I empathise with the homosexual American left-liberal who interestingly got under the skin of William “God and Man at Yale” Buckley like no one else.

An idea like Christianity or Islam was all but inevitable. As human civilisation grew more complex, as polities grew larger, as economies became more interconnected it was a matter of time before someone got people under the banner of “One Only Revealed God vs False Gods” (which is very different from monism or henotheism).

It was tried first in ancient Egypt, quickly buried, there were some signs of it in Iran, then it rose again with Moses, this time successfully though in a localised format, and finally proliferated through two world religions.

Earlier, people were (obviously) fighting each other since time immemorial but religion per se was not weaponised. Gods were all around you, even within you — there was no idea of a Jealous Father Sky-Figure condemning idolatry and Other Gods which were all deemed Satanic.

For earlier, you would respect the Idols and Temples of your adversaries as well, and see in their Deities, yours. This “translation” tendency, this syncretism, was intuitive and universal, especially in the more cosmopolitan regions, the global crossroads.

Think of what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan, and think of that region two millennia ago, when it saw the near-seamless worship of Hellenic, Vedic, Buddhist, Zoroastrian and other local as well as foreign deities.

But such overlap meant that “all of society” could not necessarily be mobilised through hatred for wars, a non-trivial disadvantage, as there were no theological demarcations as concrete as those under “counter-religions” or “secondary religions”.

Of course, there were differences and great diversity within primary “religions” too, pluralism being the point, but at the lay man level there was a certain fluidity and at the elite level there was a deliberate synthesis.

Against this relatively decentralised model, stood an epic threat. Monotheism was an Organisation super-hack, a proto-centralising ideology, the state before the state, against which all Polytheisms and Paganisms and Animisms had no chance.

Well, almost all.

For if one counts Marxism as the third proselytising monotheism (a stretch but plausible), then practically all the ancient civilisations of the world — China, Europe, Africa, Americas, Iran, Egypt, large parts of Indo-Chinese and Central Asia — fell completely at least once, except perhaps India but she came close too. We can add Japan also, depending on the size cut-off. Indeed, the southern half of Africa has been converted only within the last century or so.

But this seemingly unending victory march had the seeds of its own undoing. For the problem with Exclusive Truth Claims is brittleness. The simplicity, clarity or lack of ambiguity eventually becomes a weakness because of dogmatic schisms.

When growth hits external barriers, internal divisions amplify. Iran — channelling Ferdowsi, patronised by Mahmud of Ghazni interestingly — never gave up on its pre-Islamic heritage completely and under Safavid rule, became a Shia thorn between Mughal Hind and Ottoman Khalifa.

In Europe, things went further. While the Orthodox-Catholic split remained unhealed, the fall of Constantinople led to many ancient Greco-Roman works being rediscovered in the Italian city-states. Lucretius (their Carvaka) was found, and so was neo-Platonism with the roots of that tradition having some Indian connections as well.

Meanwhile, as Baltic paganism was exterminated by the now-converted Teutons and further expansion blocked for now, the Germans under Luther realised they did not like being sold indulgences by Rome.

Count in the printing press and the religious outflanking which only literalism could provide and we get the austere, more iconoclastic Protestant “reform”. This was replicated in the last few decades by the rapid growth of the fundamentalist strains of Islam across denominations (although the genesis goes much further behind), tired of their states being controlled by unbelievers or the much richer West, with mass media and the Internet being today’s Printing Press.

However, there is a fly in the ointment. The Protestant revolution and Catholic reaction in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries triggered a wave of genocidal bloodletting in Europe with such large fractions of the population dying, at least in some parts, which had not happened since the Black Death almost three centuries earlier. (The mercantile Jewish minority were easy targets anyway within Christendom despite the post-Holocaust retrospective rebranding of the West as Judeo-Christian.)

It is this industrial-scale fratricide, again mirrored to some extent from Pakistan to Syria in recent years, that gradually brought Europeans back to their senses, starting with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

They slowly prioritised nation over religion, again as the Arabs are starting to do now, and when racial and linguistic chauvinism got the better of them again three centuries later, they got down to the European super-state project as part of the now-broader trans-Atlantic West.

The Anglo-subset of the West, still Protestant (but often with “deist” Enlightenment elites) and with racial arrogance, conquered India with the reluctant help of some Indians, many of who saw the Turco-Mughal feudal order as worse and did not have an indigenous alternative with caste preventing the formation of a united Hindu polity while nonetheless also slowing conversions.

Whether a Reconquista would have been completed under Marathas or someone else is besides the point — the Maratha Empire never properly controlled the Gangetic Plains — because the world was getting smaller thanks to technological progress. Europe was now a global player.

Yet this second colonial encounter, while brutally exploitative, was not entirely calamitous, as Girilal Jain and others noted. Starting with early nineteenth century Bengal, and spreading across Bharat within decades, a Hindu renaissance began.

Different strains focused on different things — social reform uplifting women and ‘lower’ castes, Vedantic universalism combined with European scientific education, and so on.

Soon there was a pan-India elite that could expose the British cant in their own language. Mahatma Gandhi massified the movement, Subash Chandra Bose provided the external threat, Mohammed Ali Jinnah for his own reasons violently removed the strong version of the Muslim veto, Sardar Patel provided unity, Nehru stability — and India was finally free albeit partitioned.

Hindu Dharma had its own subcontinental-scale state after a long time, and a modern democratic republic for the first time where modernity implies socio-political mobility and economic-scientific growth.

More importantly, Global Paganism had finally its own Organisation super-hack — a state with massive latent power — though given mass poverty and ideological confusion it was anything but evident at that time. Somnath was reclaimed despite Nehru’s opposition and Gandhi’s partial blessings, but that was about it.

As India slowly healed, started to prosper and become more coherent — the ever-increasing Nehruvian appeasement of proselytising minorities began to rankle more and more. Integrating Kashmir and especially reclaiming, building a grand temple for Lord Ram are symbolic of this surge — which still has a long way to go within India itself.

But the next phase, maybe starting as soon as the next decade, will be global not national. Christian demographics in the West are falling very sharply, and the consequent “crisis of meaning” can be seen in their more polarised politics. In that vacuum, many are “agnostic”, “atheist”, “spiritual but not religious” yet for many it seems to not satiate their souls.

There are small neo-pagan revivals proliferating rapidly but from a tiny base. Pagan temples are being constructed after centuries in Europe, not counting the brief violent phase during the French Revolution.

Hinduism has made global inroads through Yoga and Mindfulness, through the practice of cremation and environmental sustainability, but often without a label — and that is fine too.

As the Global South grows richer and more educated, as people climb up the Maslow’s Pyramid and as women become freer, dogmas will no longer suffice. Dharma will be needed. The anxiety that some will have about the revival of Dharma, of that immense syncretism, will be natural. Yet the larger trends are lining up favourably.

It could well be that, in the 2120s, large parts of humanity may be celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Ayodhya Ram Mandir — as that rare thing, a genuine turning point in human history.

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Harsh is an investor, and the coauthor of two books - latest being 'A New Idea of India'.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.