Culture

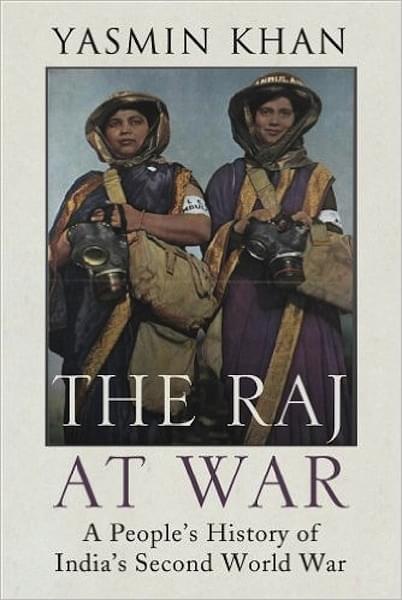

How India's Merchant Seamen Fought For Britain

Book Excerpts

Sep 12, 2015, 06:53 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 09:15 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

One of the unsung stories of the second World War is of the Indian Lascars or seafarers engaged in the service of the British Empire. An excerpt from Yasmin Khan’s The Raj at War.

There were also many Indians living in Britain who did experience the real dangers and hardships of wartime cities at first hand. When the first phase of the Blitz was unleashed in September 1940, the Indian YMCA hostel in Bloomsbury was bombed and had to be evacuated. Savitri Choudhary, who was married to a doctor in Kent, slept in an Anderson shelter in her back garden with her husband, maid and children, and comforted local women whose sons had gone to war and were missing or killed.

‘Many a fierce battle was fought over us while we hid in our shelters like primitive cavemen and women, hoping and praying that they wouldn’t drop their load on us’. Mira Lam and his family were bombed out of the Toxteth area of Liverpool. Dr Baldev Kaushal, a Punjabi with a large surgery in Bethnal Green, was awarded an MBE for his ‘gallant conduct’ during the Blitz. By the end of the year, Indian Lascars recruited from ports and docks into the Military Pioneer Corps were clearing debris from the bombed tube station at Sloane Square.

Ideological demands for Indian freedom were entirely compatible with participation in the war effort. ‘We want to serve as free and willing human beings’, declared Aftab Ali, the president in 1940 of the Indian Seamen’s Federation in Calcutta, which supported Indian merchant seamen. Many of these seamen or Lascars originated from eastern India. They could be seen meeting each other in cheap cafes frequented by Indians, smoking, going for prayers, sitting around together in their overalls and distinctive topis. Many were illiterate but would find someone to write a letter back to a home village.

Badly dressed, particularly for the British winter, and with meagre wages in their pocket, some found shelter and comforts at establishments like the Mersey Mission to Seafarers, where they might play board games or listen to the radio. Many of these men had been on the crews of ships that were now being refitted for war and as they waited for the ships to be turned around, some ventured inland. They made calculations about the risks that might be involved in sailing across the Atlantic or through the Mediterranean. Around the ports of empire, from Liverpool to Calcutta to Hong Kong, seamen had started to raise their voices, demanding war bonuses, compensation in case of death and increased wages in the face of the rising prices of commodities.

The Lascars had been hired on ships for three centuries as cheap labour. They had hard and peripatetic lives. Their monthly pay was £ 1 17 shillings compared to the £ 9 12 shillings earned by European seamen for the same work at the start of the war. By 1938, 50,700 of the sailors employed on British merchant vessels were Indian or just over a quarter of the total number. The Lascars had a poorer clothing allowance, worked longer and less regulated hours and slept in more cramped quarters.

They ate a cheaper diet and suffered more ill-health. The system had barely evolved since Victorian times and was a particularly suitable target for labour leaders both in Britain and in India. Anachronistic even by the standards of the time, it was criticised by the Labour politician Aneurin Bevan as providing ‘cheap human fodder’ and a potential source of embarrassment for the British government. The war proved the catalyst that would lead to at least some changes in the Lascars’ conditions, although real change would only come after the war.

A wave of strikes and protests broke out in ports around the empire in late 1939 and early 1940. Mass arrests took place. Some Lascars had prison sentences with hard labour for up to twelve weeks. At the end of October 1939, forty Indian seafarers from the SS Clan Alpine got two-month sentences for ‘willful disobedience of lawful commands’ and men from other ships berthed in London, SS Britannia, SS Somali and SS City of Manchester, received prison sentences for striking. Four hundred Lascars were imprisoned in the UK at the end of December 1940. Strikes erupted in other ports as far afield as Cape Town, Burma and Australia as the word spread around the seafarers’ global networks…

…Some of the Lascars came from families with generations of experience on sailing craft that plied the Indian Ocean or the Konkan coast. Goan Catholics worked as stewards, Muslim smallholders from Chittagong and Sylhet manned the decks, Punjabi and Pashtun ‘agwallahs’ (literally fire-men) stoked the engines in the boiler rooms. Others took to seafaring from rural inland districts and had never seen the ocean before. They were rounded up by serangs, the middlemen who acted as boss, big brother and overseer to the seamen.

Even when away from home for years at a time, the Lascar still thought of home. By leaving home, the Lascar removed an extra mouth to feed, and while siblings tilled the land, or wives wove and stitched handicrafts, they sent back remittances, enabling the family to buy more animals or a small patch of land. Far inland, children of the Lascars looked at pictures of steamships sometimes proudly kept in the family home, imagining their absent fathers…

…On 18 September 1940 a German U-boat torpedoed the SS City of Benares in the Atlantic. Seventy-seven British children, many as young as five or six, who had been sent as evacuees from Britain to Canada perished. This tragedy stunned the empire. But less well known was the fate of the Indian crew manning the ship. Of the 160 Lascars aboard, 101 were drowned or died in the shipwreck. Many of them have only ever been remembered by their forename, without a recorded date of birth and with the simple epithet ‘boy’ or by the basic description of their duty on board the ship.

Soria the apprentice, Sheikh Labu, a pantry boy, and Mubarak Ali, a baker, were among those who perished: they remain little more than ghostly traces in the archive. Abbas Bhickoo, who was twenty-two years old, and from Sangameshwar, Ratnagiri, in present-day Maharashtra, was one of the Lascars who managed to scramble onto a lifeboat. With other survivors, he lay adrift on the lifeboat for eight days until they were eventually picked up and taken to the west coast of Scotland. But Bhickoo died shortly afterwards, presumably from exposure. His grave still stands in Greenock in western Scotland. Yousuf Choudhary, who as a child in Sylhet at the time, in present-day Bangladesh, remembered how the news of a seaman’s death would ripple through the community.

‘As the news came, the dead seamen’s relatives and friends would gather and begin crying and shouting…soon the bad news spread from house to house, village to village. The people became nervous, worrying that they would be next in line for this shock. The British public never heard the cry of the seamen’s widows.’ Shivers rippled through seafaring communities whenever a torpedoed ship was reported: over the course of the war 6,600 Indian merchant seafarers would lose their lives, over a thousand would be badly wounded and over 1,200 would be taken as prisoners of war.

The Raj at War: A People’s History of India’s Second World War, Yasmin Khan, Bodley Head, 2015

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.