Analysis

The Role Of State-Funded Agency DARPA In Growth Of U.S Semiconductor Industry And Lessons For India

- The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the research and development agency of the United States Department of Defense responsible for developing emerging technologies for use by the military, has played a key role in growth of U.S Semiconductor industry.

DARPA

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the research and development agency of the United States Department of Defense responsible for developing emerging technologies for use by the military, has a tremendous track record of cutting-edge, world-changing innovation.

From weather satellites, GPS, drones, voice interfaces, the personal computer, the internet, and the mRNA vaccine, the list of innovations for which DARPA can claim considerable credit is long.

In her book 'The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Private vs. Public Sector Myths', Prof Mariana Mazzucato pointed out that many significant features of the iPhone was created initially by multi-decade government-funded research. From DARPA came the microchip, the internet, the micro hard drive, the DRAM cache, and Siri.

President Dwight Eisenhower authorised the creation of DARPA in 1958 to "form and execute research and development projects to expand the frontiers of technology and science and able to reach far beyond immediate military requirements."

Many in the electronics and computer science domains may also remember the "VLSI project", which lead to Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) Unix and Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) concept, among other things.

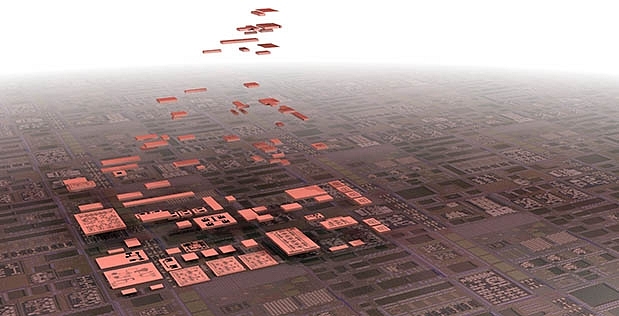

What is perhaps lesser noticed is the role this agency has played at various stages in keeping the U.S. semiconductor industry competitive and ahead in various aspects of the value chain. Before mentioning some examples of that, it may be helpful to give the following two reference pictures to know the current state of affairs on where the U.S. stands.

1) Here is a snapshot from 'Semiconductor industry value added by activity and region, 2019 (%') from semiconductors.org published by Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA). It must also be mentioned that there have been articles questioning some of the numbers and percentages in SIA reports - for example, this one hints at some Chinese numbers being exaggerated as part of lobbying for incentives in U.S.

2) While the above picture gets into various aspects of the supply chain, if we look at semiconductor (mostly Integrated Circuits, that is I.Cs) sales market share (out of a total of $555 billion for 2021 as per one of the estimates and likely based on country of headquarters of the company), the below picture recently published by DigiTimes may be a good reference. Note that revenues of pure-play foundries like TSMC are likely not included in the list, while IDM stands for Integrated Device Manufactures like Intel.

In both these categories, the U.S is the overall leader. Still, there are aspects where it isn't - chip fabrication (from starting wafers to processed wafers done in semiconductor fabs) in general and foundry (chip fabrication as a contract) in particular. This lag in some areas has been a trigger enough for the U.S. to go into alert and action mode

That brings me back to the DARPA story and a good point to start is this report published in Washington Post in early 1987.

To quote some key paragraphs

U.S. semiconductor manufacturers are trying to engineer a billion-dollar program using Pentagon money and industrywide collaboration in an attempt to regain world leadership in the production and design of advanced computer chips.

The project, known as Sematech, for semiconductor manufacturing technology, is under intense discussion among leading chip makers who want to set up a model production facility in California's Silicon Valley as a proving ground for new technology. Under the industry plan, the project would be financed equally by the Pentagon and industry, and would involve close collaboration between chip manufacturers, their customers and the companies that make the machines that produce semiconductors.

The Washington Post quoted excerpts from a draft report published in December by Electronics News, the Defense Science Board Task Force on Semiconductor Dependency.

"The Japanese cannot be relied upon to transfer leadership semiconductor technology to U.S. systems suppliers for military uses,"

It is indeed interesting that in the present scenario, a similar sentiment exists against China, and attempts are one to form an alliance comprising of U.S., Taiwan, South Korea and Japan.

The MoU leading to the formation of Sematech can be found here and the government part of the funding came through DARPA. It was not a smooth start going by various studies some of which are listed below, but eventually showed results:

a) This 1995 study titled "Building Cooperation in a Competitive Industry: SEMATECH and the Semiconductor Industry" which as per the synopsis describes "three core categories of events and behaviors: (1) the factors underlying the consortium's early disorder and ambiguity, (2) the development of a moral community in which individuals and firms made contributions to the industry without regard for immediate and specific payback, and (3) the structuring that emerged from changing practices and norms"

The document also has a wealth of other information, for example, the name of the 14 founding companies.

b) A 2011 thesis titled "Assessing the Success of Dual Use Programs: The Case of DARPA's Relationship with SEM s Relationship with SEMATECH—Quiet Contributions t TECH—Quiet Contributions to Success, Silenced Partner, or Both".

The definition of "Dual Use Program" include "programs [that] typically involve consortia that include commercially oriented firms. The research agenda is negotiated with industry and aims to address the common needs of both the commercial and military sector"

As per the SEMATECH history (archived here) - By 1994, it had become clear that the U.S. semiconductor industry—both device makers and suppliers—had regained strength and market share; at that time, the SEMATECH Board of Directors voted to seek an end to matching federal funding after 1996, reasoning that the industry had returned to health and should no longer receive government support. SEMATECH continued to serve its membership, and the semiconductor industry at large, through advanced technology development in program areas such as lithography, front end processes, and interconnect, and through its interactions with an increasingly global supplier base on manufacturing challenges.

A key 'global' contribution from SEMATECH that is still relevant is establishing the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering (CNSE) of the University at Albany-SUNY (history from 2002 from 2012 is listed here).

As per this website, ""CNSE's Albany NanoTech Complex is a $12 billion, 800,000-square foot (74,000 m2) complex that includes an industrial-scale 80,000-square-foot (7,400 m2) cleanroom "as well as a collection of equipment perhaps unique in the world" The cleanroom space is Class 1-capable and houses a fully integrated, 300 mm wafer, computer chip pilot prototyping and demonstration line. More than 2,500 scientists, researchers, engineers, students, and faculty work on site at CNSE's Albany NanoTech Complex, from leading global companies including IBM, AMD, GlobalFoundries, SEMATECH, Toshiba, Applied Materials, Tokyo Electron, ASML, Novellus Systems, Vistec Lithography, and Atotec".

So when you hear that despite selling off its commercial fabs in 2015, IBM has been part of developing nanosheet based 5nm transistors (along with Samsung in 2017, which is likely to be the base for what Samsung will commercialise in its 3nm chips), 2nm nanosheet based chips in May 2021 (as per this news) and vertical transistor architecture (along with Samsung in Dec 2021 as per this news) we have some clues of which facilities it must be using

Another program that DARPA funded is the Metal Oxide Silicon Implementation Service, or MOSIS. The service provided a fast turnaround (four to ten weeks), low-cost ability to run limited batches of custom and semi-custom microelectronic devices. By decoupling researchers from the need to have direct access to fabrication facilities and negotiating the complexities of producing microelectronic chips, MOSIS opened innovation in this space to players who otherwise might have been precluded. A key aspect of MOSIS was the pooling of several chip designs onto a single semiconductor wafer (Multi Project Wafers or MPWs). MOSIS opened for business in January 1981 is still available

30 years after SEMATECH, perhaps sensing the China factor, DARPA announced the "Electronics Resurgence Initiative" (ERI). "a need for alternative approaches to traditional transistor scaling" was mentioned in the goals, but also "non-market foreign forces are working to shift the electronics innovation engine overseas and cost-driven foundry consolidation has limited Department of Defense (DoD) access to leading-edge electronics, challenging U.S. economic and security advantages"

Whether as part of ERI or not, initiatives where DARPA is involved include Automatic Implementation of Secure Silicon (AISS) , Structured Array Hardware for Automatically Realised Applications (SAHARA) and there are also other DoD projects like Rapid Assured Microelectronics Prototypes-Commercial (RAMP-C) and State-of-the-Art Heterogeneous Integration Prototype (SHIP). In most or all of these programs, collaboration with industries is a key

The DARPA budget documents for various years can be accessed here . The 2022 (FY22) budget request was for $3.528 billion and the document has multiple references of microelectronics.

As of 20 April 2022, there was news of DARPA's FY23 budget investment areas and the list read as

$896M Microelectronics

$414M biotech

$412M AI

$184M cyber

$143M hypersonics

$90M quantum

$82M space

As closing remarks, what are the parallels that one can draw to India ? One key difference is that many of the efforts by DARPA were in collaboration with already well-established industries with a good market lead or presence.

For India, many areas - commercial fabs in particular - need to be start afresh.

India may need a mix of lessons learned from DARPA (and similar examples from other countries) combined with an understanding of India's own capabilities and priorities to help evolve a model for the interplay between defence and a hoping-to-emerge commercial semiconductor ecosystem.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest