Books

Amish's 'War of Lanka': A Trendy Literary Portal For Youth Into The World Of Ramayana

- This is not exactly a retelling of the 'Ramayana'.

- Rather, Amish takes it upon himself to create a portal into an Indian universe of fantasy for the current, English-speaking Indians—bewitched by Tolkien and Rowling.

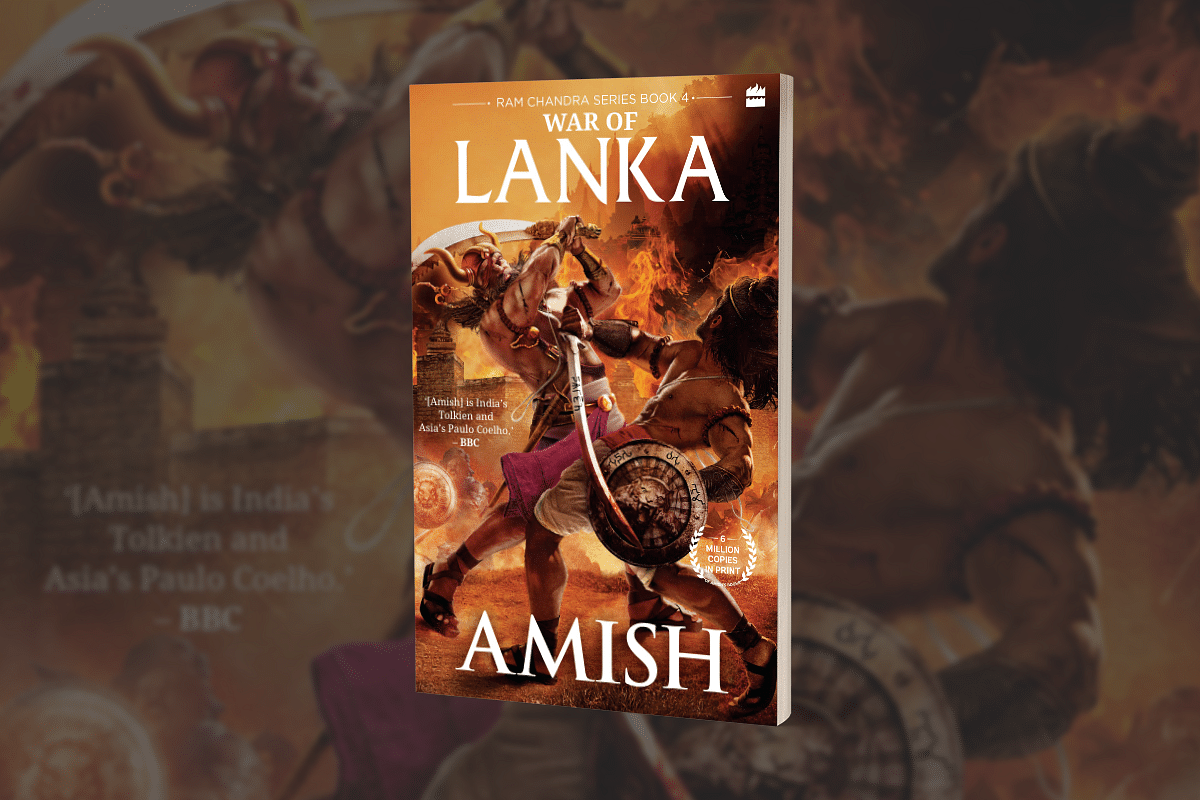

'War of Lanka', fourth book in the Rama Chandra series.

War of Lanka (Ram Chandra Series Book 4). Amish. HarperCollins India. Pages 500. Rs 240 (paperback).

Amish has been a sensation in a new way of story telling. For an entire new generation of English-educated Indians, he has been one of the prominent channels through which the great Indian epics are being transmitted.

That is a great responsibility.

Initially, Amish was weaving the narrative for ancient India through his fiction series – the Shiva Trilogy. Then through Ramachandra Series books he has taken up the challenge of Ramayana.

That is a magnificent challenge.

Valmiki was the Adi-Kavi of Indian tradition. He was in empathy with the pain of the bird that had lost its companion to the cruel arrow of a human. Valmiki resonated in his being with that pain.

From that pain was born the first shloka, our tradition tells us. That is the state and expanse of heart demanded by our tradition to be the creator of an Itihasa. Except for Maharishi Sri Aurobindo, none come closer to create an epic from that consciousness.

The mission of Amish hence is not exactly a retelling of the Ramayana. It is creating a portal for the current, English-speaking Indians—bewitched by Tolkien and Rowling—to enter into their one universe of the fantastic. And he has done an exemplary job at that.

The Ramayana of our popular understanding has many streams - great Itihasa Srimat Ramayana of Valmiki, the literary and spiritual masterpiece Irama Avataram of Kamba Nattazhwar, the devotional, musical, and moving Sri Ramacharitamanas of Goswami Tulsidas and not to mention a million ever evolving art forms of millennia -from Therukootu to Bharata Natyam to Kathakali.

The ‘Ramayana that we know’ is the emergence from all these streams. Taking that ‘Ramayana that we know’ as the basis of creating a fantasy portal for the current generation again is no simple exercise. It is filled with landmines and abysses.

One should say that the text of Amish avoids these landmines and abyss-pits quite brilliantly.

What does it create?

If one expects just a modern retelling of Ramayana then this is not for you.

The text does not retell the Ramayana but it tells a creative fiction that Amish has created using the Ramayana as context, fusing it with the emerging knowledge that we have of the ancient world of Ramayana times.

A good example of what the text gives can be seen below:

The above passage is typical of the way Amish integrates ancient lore with modern knowledge that we have gleaned about the ancient history through archaeology. One is both fascinated and has problems with such narration.

Fascinated because the way in which Lothal has been colourfully made alive woven into the ever- lasting Ramayana texture. Think of a high-school child who has read War of Lanka and then reads about Lothal in her history textbook.

Lothal will be a dynamic memory, more than the dull half-visible photo and a five-marks-fetching answer to be memorised for the test and forgotten as you grow up.

Amish opens up the imagination of a new generation—through the context of Ramayana—to one’s own history with the respect that history deserves – which has been denied so far.

Perhaps a history textbook having a box-item of above quote can also ask the child what he thinks about Lothal being used during Ramayana and Mahabharata times.

The way Amish's text of Ramayana can opening up pedagogic possibilities for history teachers is immense, efficient and useful. One hopes the history text-book writers make use of such resources in innovative ways.

Now the problem I find in the passage is the way Naarad has been described. There is a danger of an impressionable mind taking this picture of Naarada as real. He may think that the Itihasa/Purana Naarda may be an embellishment of such ‘a realistic or historic’ Naarada.

Rajaji long back warned about this aspect of using our Itihasas and Puranas by modern writers. The young generation which has not read the original Ramayana (either Valmiki or the literary rendering in their own language) may take this portrayal as the true one.

That said, the book takes some very curious strands from popular variants of the Ramayana and weaves them into the possible dynamics of ancient cultures that spread throughout the greater Indian landmass.

Some of these re-portrayals may not be to the taste of the traditional lovers of Ramayana. But the author has not tampered with the basic spirit of the great Kavi-tradition.

Ravana has always been an enigma. He becomes the personification of evil. But he is also a celebrated personality. There is nothing grand in the evil deed of an evil person. But there are lessons of tragedy, almost poetic and empathetically painful in the fall of a conflicted personality of great grandeur.

The entire life of Ravana as revealed by our traditions – central as well as ever-evolving traditions – is that fall. At every point he shows greatness and at every point that greatness does not lead to an elevation but fall.

So, for a human mind it is as easy to worship and adore Sri Rama as Avatara Purusha as it is to empathise with the pain and fall of Ravana. One thinks this may have been deliberately done by the Kavis.

It contains a poignant spiritual-psychological point. We are all worshippers of Sri Rama with a potential seed of Ravana in us waiting to sprout. We know that is a tragedy and a fall. Yet we are mysteriously and dangerously attracted to Ravana.

More our Rama Bhakti, surer the vanquishing of that Ravana. More we give ourselves to Hanuman, faster we recover from the fatal wounds the inner battle with Ravana inflicts upon us.

Maruti needs to feel the radiance and command of Sri Rama inside us to bring the mountain of life-rejuvenating and healing herbs. Sometimes the Sri Rama-Ravana battle may continue through generations.

So Ravana has always been an enigma.

Employing this enigmatic lure of Ravana in the re-imagination of Ramayana context is done with skill by Amish. The legend of Vedavati is a very pervasive one in southern parts of India. Ravana was madly in love with her. There is also the legend that Ravana was actually the father of Sita. There have even been devotional movies based on these legends. Amish combines these legends while creating a few of his own.

In this retelling, Bharat had been portrayed as kind of a philanderer in the previous Ramachandra series. Here, he comes with the Ayodhya armies to Lanka to help his brother – who is technically a king-in-exile. Sursa is in love with Hanuman and dies in his hands. Rama sits and talks an alliance with Vali who in turn calls Sri Rama for a duel.

Such portrayals, while not be very suitable to a mind immersed in the devotional environment of Ramayana, may add spice to the readers of the current generation.

There is a critical mass of such portrayals. If such portrayals do not demean the basic spirit of the Itihasa and the Dharma that it carries in its heart, then they can be seen as the test of the healthy creativity of the author. One can surely tell that Amish is well within that boundary.

At multiple levels the book is a treat. It is a fast-paced novel for the youth. It familiarises the English-speaking youths of India with the Ramayana and its landscape as well as communities of ancient India. It becomes a pedagogic tool for entering into the domains of history and archaeology – with a sense of belonging – not as English-education-induced-foreigners-to-our-own-history.

It is a trendy literary portal to take the youths into the realm of the Adikavya.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest