Books

Book Excerpt: When A Caretaker Prime Minister Had To Lead The Country During A National Security Crisis

- The last thing a caretaker government wants to be worried about is a threat to national security.

- That's exactly what Atal Bihari Vajpayee had to deal with in 1999 after his government fell by one vote.

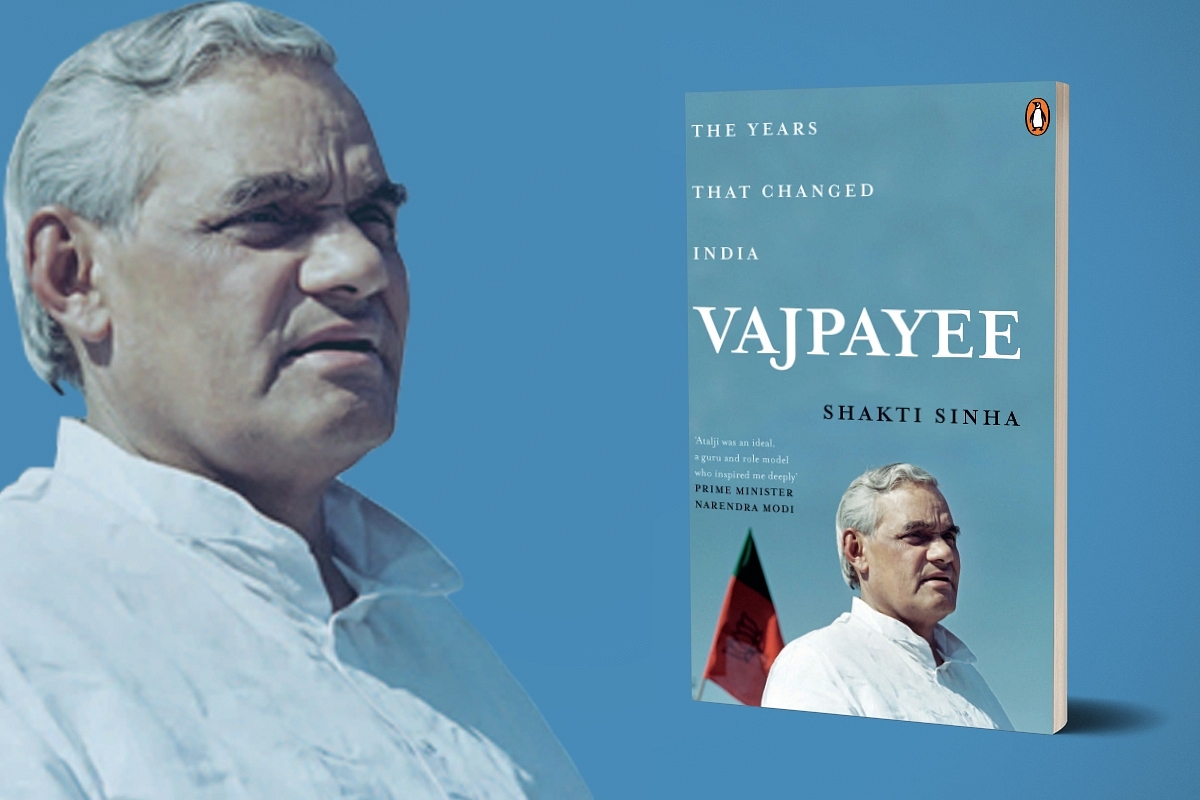

Vajpayee: The years that changed India

Vajpayee: The Years That Changed India. Shakti Sinha. Penguin Random House. 368 pages. Rs 529.

Politically, the weakest moment in a country’s life is when it is run by a caretaker government. What made the situation worse for India was that the caretaker status of the Vajpayee government was going to be a long one. It had lost the vote of confidence on 17 April and mid-term polls would not be concluded till early October, a period of nearly five months. What worried us greatly was that economic decision-making would suffer. An economy that had been in a downward spiral since 1996–97 was finally turning around, or at least the shoots of revival were visible. What impact would a caretaker government have on the emergent growth momentum? Under such conditions, the last thing that Vajpayee and those around him could have expected to worry about was a possible threat to national security which would pull the country into a state of war. But, as fate would have it, that is exactly what happened.

It was mid-May, possibly the seventeenth, when Brajesh Mishra informed Vajpayee, in my presence, that there were cross-border developments in Kashmir that might become a cause for concern.

The exact nature was not clear, but Mishra seemed anxious and said that the army was soon to provide a detailed briefing about the situation on the ground. The next day, we went to the Ops Room in South Block, where the then director general of military operations, Lt Gen. N.C. Vij, later to be the army chief, conducted the briefing. Apparently, groups of Mujahideen had crossed the Line of Control (LoC) that separated India and Pakistan in the then State of Jammu and Kashmir.

While infiltration of jihadi terrorists from Pakistan had been going on for years, what was different this time was that these groups of Mujahideen were larger in numbers and had occupied the heights of Kargil. At this point, the army had not been able to determine the places where these intrusions had taken place and the numbers of fighters involved. As the story emerged then, two Ladhakhi shepherds had gone up the snow-clad mountains to look for grazing lands when they spotted a group of men in salwar kameez, popularly known as Pathan suits. This was reported to the local army units, which sent up a patrol to investigate. The patrol did not return. However, the situation was not assessed to be very serious, since the army chief, General Ved P. Malik, had proceeded on a ten-day foreign tour and was not cutting it short and flying back. It thus seemed at the time that while the situation may not be normal, it wasn’t critical either.

This was a shock, actually, in retrospect the first of many, even more serious ones. After the success of the Lahore visit, the general view was that even if normal, peaceful relations between India and Pakistan would take time to establish, a good beginning had been made. Between the two main parties of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League (PML) was seen as having an Islamic character, as against the more secular-inclined Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). Sharif and the PML were, in fact, creations of the Pakistani Army, though Sharif had tried to make himself an effective chief executive. So if Sharif was trying to mend relations with India, it could be presumed that Indo–Pak relations would certainly not deteriorate.

From Colombo and New York to Lahore, Vajpayee and Sharif had built a good equation. After the Kargil infiltration, there was anger in India at Pakistan and at Sharif, though there were some doubts right from the beginning about how much the latter was actually involved. In any case, an angry frame of mind could not have been the starting point for decision-making. The orders were clear: the intruders had to be evicted. The initial estimate was that it would be done in a matter of a few days, or at most in a couple of weeks. But, as subsequent developments were to show, these estimates were completely off the mark.

The Mission was much more complicated than just throwing out a group of Mujahideen. Both armies had followed the standard drill of vacating their posts high in the hills when they became snowbound and went back to those altitudes in spring, around mid-to-late-May. What made the Mujahideen narrative a little difficult to digest was the geography of their chosen altitude of attack and their tactics. The Himalayan middle range separates the Kashmir valley from Ladakh; they are connected by a single national highway (NH1), which uses the Zoji La, a high mountain pass, to cross over. The pass is approximately midway between Srinagar and Kargil, now the headquarters of a district of the same name. The Srinagar–Leh NH1, as it comes down the Zoji La, lies quite close to Drass, whose heights, occupied by enemy forces, were perfect for interdicting traffic movement on the highway. Drass and the nearby Mushkoh valley, south-west of the Kargil town, represented the western-most extremity of the Ladakh region.

It was soon clear that the infiltration was substantial. The first intrusion by the shepherds had been in Batalik, north-east of Kargil. The Drass–Leh–Batalik line running from south-west to north-east is about 160 km, and the intrusions were 2–10 km deep, 6–7 km on an average. The question that was bothering us the most was simple: Why would the Mujahideen occupy snowy heights with no habitation, when their supposed strength lies in carrying out hit-and-run/suicide missions in populated areas? A Mujahideen action is normally meant to generate wide publicity and frighten the population, forcing their governments into conceding to the certain demands. But if the Kashmiri Mujahideen were occupying unpopulated areas along the LoC, could it be possible that they were trying to actually win territories from the Indian state? And if this were true, how did the Mujahideen have the necessary logistical capacity to place these many fighters and occupy hundreds of square kilometres of the Indian territory? While these and other related questions did bother us at the time, in retrospect, nothing much was done to seek their answers.

Vajpayee belonged to a tradition that believed India’s perceived pacifism had hurt the nation, cost it its independence and allowed invaders to subjugate it. Further, he held that independent India had not done enough to be able to defend itself militarily. This meant, among other things, that the armed forces had to be given a free hand in battlefield tactics.

Excerpted with permission from Penguin Random House India.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest