Books

Book Review: Sri Aurobindo And The Literary Renaissance of India

- Even as this reviewer does not agree with everything said in author Pariksith Singh's book on Sri Aurobindo, the book is stimulating and provides the reader with reason and motivation to read more of Sri Aurobindo for herself.

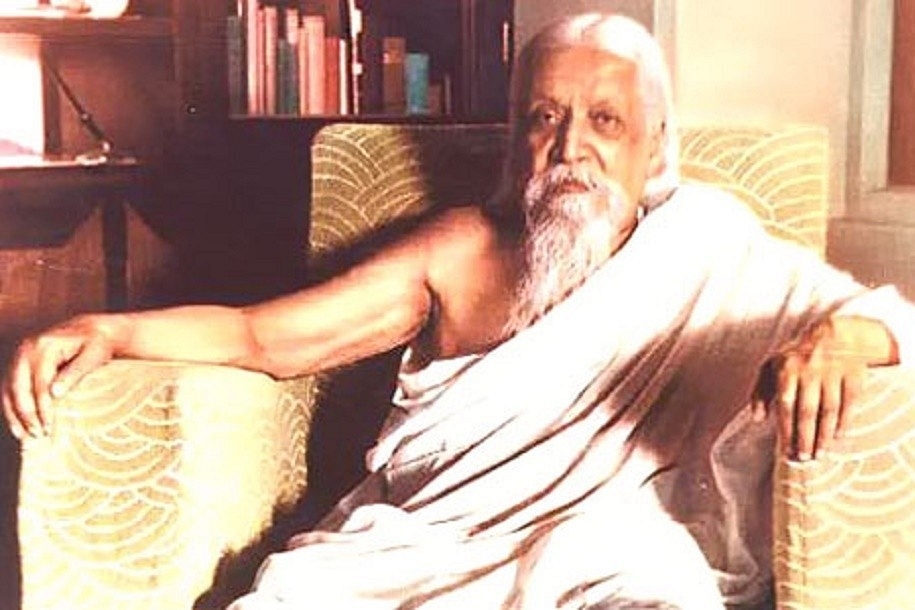

Sri Aurobindo.

Sri Aurobindo And The Literary Renaissance of India. Pariksith Singh. Kali BluOne India LLP. Pages 414.Price Rs 995.

Sri Aurobindo is always venerated as Mahayogi and Mahatapasvi. He was a genius who was an evolutionist visionary, poet and a philosopher of the highest order. Studying the enormity and intensity of his works should take for anyone a few dedicated life times.

To even start understand the place of Sri Aurobindo in the context of planetary human evolution, one should know Eastern wisdom and Western philosophy, and the inner sciences as explored by the rishi tradition of India and by two centuries of Western psychological sciences.

That is what makes the present book by Dr. Pariksith Singh interesting. A medical doctor, he is also a poet. He has an intense admiration for the works of Sri Aurobindo and in this book of 400 and odd pages he has tried to present the diverse dimensions of the spiritual master.

The canvas he has taken is vast and challenging.

In section I, the thoughts of Sri Aurobindo get compared with fifteen eminent thinkers from around the world and from across history. Starting from Wittgenstein we move through Nietzche, Heraclitus and Spinoza to Derrida, Heidegger, Huxley and Buber – to name a few – each a titan of philosophy.

Here, the problem is that Sri Aurobindo is not a builder of philosophical systems as a philosopher and his functions are known in the Western tradition. Dr. Singh, right in the very first essay, ‘Sri Aurobindo and Wittgenstein’ sets the tone to deal with this fundamental contradiction that runs through all his essays:

Then 63 pages later in his essay ‘Sri Aurobindo and Heidegger’ we read that Dr. Singh considers Heidegger’s view of poetry as ‘establishment of being by means of the word’ as ‘perhaps one of the best descriptions of the mantra'. This superficial contradiction is to show the immensity of task that the author has taken upon himself. When one deals with Sri Aurobindo in such a daring canvas absence of such contradictions would actually be an indication of deficiency of the study.

The comparison between Spinoza and Sri Aurobindo is quite interesting. Dr. Singh writes:

Dr. Singh makes here a laudably valiant but unfortunately unsuccessful attempt to map Christian Trinity as signifying ‘the three aspects of the Divine, that which is transcendental-cosmic-immanent as one reality.’ There are some serious problems here.

The Father-Son-Holy Ghost has no such connotations. It is a mystery of the Personal God. Christianity unlike Judaism and even to an extent Islam, never bothered much about the connections between impersonal and personal as well as extra-cosmic and immanent aspect of the Deity. For the Christian God is extra-cosmic and Personal. Even the first verse of Gospel of John where the seemingly impersonal Word (borrowed from Greek Logos) becomes flesh in Christ, it is the Personal that makes the verse spiritual for Christian faith.

Further, Vedanta is not only Advaita and Advaita is definitely not monism, it is non-dualism. Between the binary of the monism of the mind and matter that plagued better part of Western philosophy, Spinoza is indeed a fresh breeze. While his ‘Substance’ gave way to him being thought as a monist, the infinite attributes of the Substance and the knowledge of the three kinds (very similar to Saiva Siddhanta’s Pasu-Paasa-Pathi Arivu) makes Spinoza more a non-dualist than a monist.

Then he tries to see pantheism in Jesus:

The problem is Jesus never spoke of bread as his flesh. He said his flesh was the bread and his blood was the wine. Not just any bread and any wine but a magical blood and wine that cleanses all the sins. In other words, the 'this day our daily bread' of Lord's Prayer is not the body of Jesus. It is a food made available by the Lord but not Lord Himself. So at the time of holy communion the bread and wine actually ritualistically transforms into his blood and flesh. By no stretch of text twisting can this ritualistic magic be considered as pantheistic.

The good doctor could have sought Teilhard de Chardin, who actually envisioned a Cosmic Christ – more through his study of evolution than because of the Gospels. Sri Aurobindo and Chardin were contemporaries and striking parallels exist between the two.

Amal Kiran (K.D.Sethna 1904-2011) has authored a wonderful book on Chardin way back in 1976. Those who wish to understand the Hindu-Christian encounter along with Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel should also read K.D.Sethna. Not that Christendom is incapable of arriving at eternal truths even through Christianity. Consciousness expressed through humanity ever seeks to accomplish that.

The line attributed to Lord Byron, explaining the perhaps the borrowed-from-Dionysus miracle of Jesus turning water into wine, reads ‘Water met her Master and blushed.’ A faint poetic glimpse of Purusha Prakriti can be seen here – not fully developed perhaps, not even comprehended beyond the immediate thrill of perspective, but it is there.

This shows the universality of Sankhya Darshana but not Jesus symbolizing Sankhya through the miracle. Claiming otherwise would be doing grave injustice to both Jesus and Sankhya Darshana. This is a fallacy well-meaning scholars in universal spiritual quest like Dr. Singh should avoid.

Both Sri Aurobindo and Chardin being visionaries of evolution in their own right, it would have been a great delight had Dr. Singh made a comparison of both. One should remember when reading each of these 15 essays of comparison, that these essays are seed forms of a book in themselves.

Also, one hopes he would in future expand each of them. He has shown as what a treasure we have for humanity in Sri Aurobindo. That is itself is a task worthy of immense gratitude. If he sets out to expand each of his essays that would be a gift for posterity.

As we move on the book deals with Sri Aurobindo the poet and the playwright.

Dr. Singh is himself a poet and so his appreciation of Sri Aurobindo is both that of a scholar and a fellow poet. To him, achievement of Mahayogi as poet are three fold – in terms of content in which he made English verse a vehicle for expressing very refreshing Sanatana Darshanas, then in terms of experimenting with the form and thirdly, Savitri.

Again it is not an easy task that the author has taken upon himself and he is definitely in an unenviable place. There are pages where one can feel the author holding the hand of the reader and walking him through the beauty of the palatial poetic mansions of great European poets and then into the enchanting eternal forest that is Sri Aurobindo’s poetry.

In Section-IV, in an essay provocatively titled ‘Sri Aurobindo and the Scandal of the Vedas’ there is quite an amusing passage:

One needs to say that here the author has taken a typical Western view of Indian history – 'ritualistic darkness versus reform through true religion etc'. Sri Aurobindo himself did not subscribe to such a view of history. In this typically Western view of history, Upanishads counter ritualism, Buddha counters ritualism, Sankara counters ritualism.

Vedic ritualism (and in a more hostile parlance Brahminical priestcraft) is the Satan to be stoned at on the way to the Mecca of rational liberation. But Sri Aurobindo does not see history so. Not that he does not know about the problem of extreme ritualism:

But had Sri Aurobindo stopped here he would be, at best, just another Anglicized Hindu-phile Hindu reformer. He goes further and deeper:

It does not matter whether one agrees with Sri Aurobindo or not but one needs to read this particular pages in his Secret of the Vedas for they provide a refreshing way of looking at the evolution of a religio-spiritual system in a holistic way.

For centuries if not millennia the global civilizations have been conditioned by binary dynamics in studying religion. There have been conflicts between the priest class and the ruler class, between the priest class and seeker-rebels, religious authorities and mystics. India is no exception. The clash between Parasurama and the Kshatriyas to Vasishta-Viswamitra to Sri Ramakrishna’s 'Pandit and milk maid story', we can see it. We can see it in the vilification of Imhotep that persists to this day from ancient Egypt.

At a more shallow, degraded level, we can see it as the power politics of Protestant hatred for priestcraft in recent centuries of European history. Unfortunately, the last has been mapped on to all other binaries in Indian tradition, though the latter has actually attained a remarkable success in harmonizing these deeper archetypal binaries.

The colonial narrative reversed this samanvaya process. And it is to the genius of Sri Aurobindo that we should be grateful that he reversed this downfall of narrative. His approach subsumes the conflicting binary and brings out the harmonious and holistic nature of the national movement.

Further, as an aside, the definitive ‘victory’ attributed to Sankara of his version of Advaita over all other systems is more in the realm of devotional hagiography than in the factuality of Hindu historical reality. The Shanmatha Sthapana attributed to Adi Sankara is more in tune with Hindu historical reality than his victory over all other Dharmic sects.

These critical observations not withstanding the book is stimulating and provides the reader with reason and motivation to read Sri Aurobindo for herself.

The book also illuminates the varied paths through which an interested student can approach Maha Rishi Sri Aurobindo. This is highly welcome addition to quality Sri Aurobindo scholarship.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest