Books

Even As It Stops Short Of Describing The Whole Range Of Hindu Responses To German Dictator, Vaibhav Purandare's Latest On Hitler And India Is Valuable And Timely

- Purandare's book comes at a good time, for it informs a new generation about the attitude of Hitler and the Nazis towards India and Hindus.

- Although, the book could have broadened its scope by including the whole wide range of the Hindu responses to Hitler.

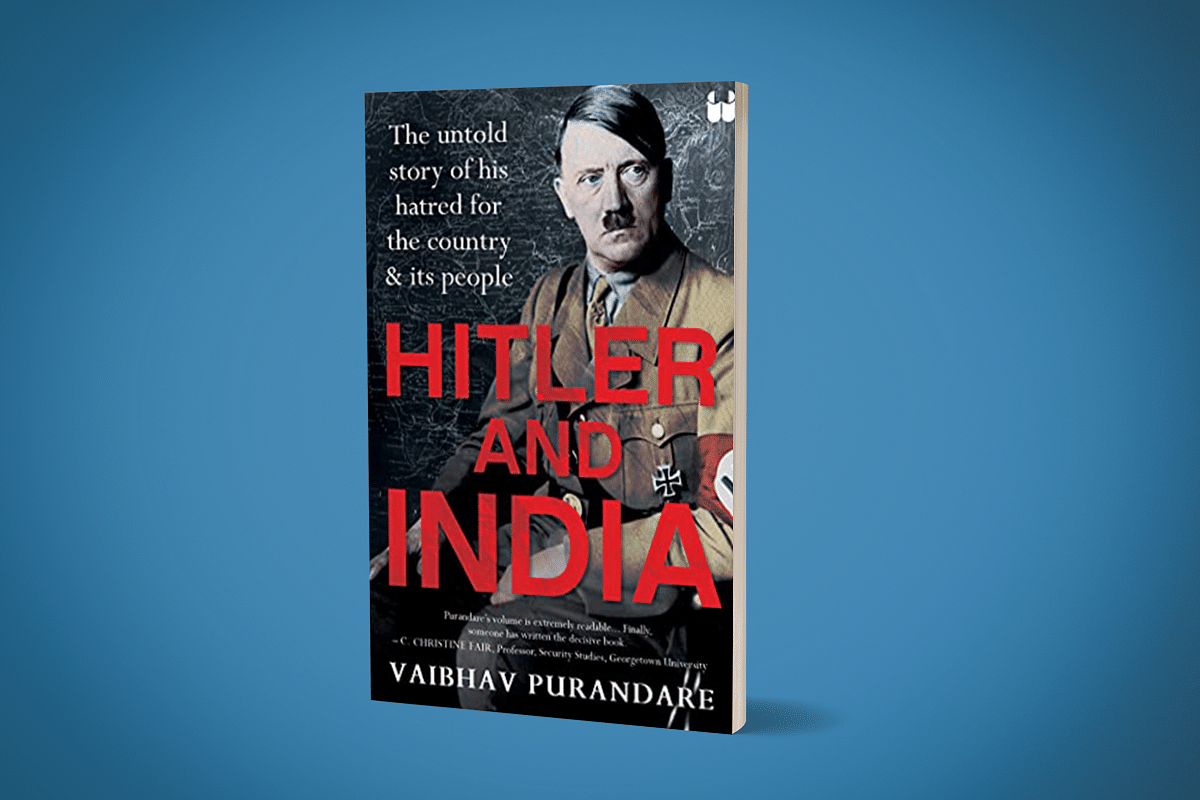

Vaibhav Purandare's 'Hitler and India'

Hitler and India: The untold story of his hatred for the country and its people. Vaibhav Purandare. Westland. Pages 218. Rs 313.

When Dravidianist ideologue C.N.Annadurai lamented that the social reality of ‘Aryan’ concepts permeating entire Tamil society prevented the use of a Hitlerian ‘final solution’ towards Brahmins, the horrors of Holocaust had become well-known. Annadurai was against the final solution not because of its inhuman unethical nature but because it was 'impractical' in Tamil Nadu.

Dravidianists were not the only ones who admired Hitler. In the Hindutva fringe, Hitler gets admired because of the use (or rather abuse) of the terms like 'Aryan', 'Swastika', his supposed vegetarianism, his alleged support for Bose and Indian independence.

Meanwhile, a dominant section of the academia, media and polity wants to tie Hindutva to Nazism and Fascism. There have been persistent attempts to project Hindutva as an Indic version of both. The fringe comes in handy in the era of social media where its voices can be amplified and projected to caricature and stereotype all the opponents.

It is in this atmosphere that the book Hitler and India (Westland, 2021) by author Vaibhav Purandare gains importance. He points out bluntly how Hitler considered Indians as an inferior race. He was uncomfortable with the idea of Indians ruling themselves. That could happen only if the British would fall down from their racial superiority or if Indians gained military superiority over the British and stage a successful rebellion to throw them out – both the possibilities, Hitler considered as improbable.

Interestingly, Hitler and Churchill, the villain and hero of the Second World War, were united in their when it came to Hindus. If Churchill had said that India would ‘fall back into the barbarism and privations of the Middle Ages’ were the British to leave, Hitler echoed the same sentiments.

After reading the situation in India where nationalists were trying to achieve freedom through various means, including using the Bolsheviks and Nazis, as also without any outside help, Hitler lamented that ‘nobody cares about the state of anarchy that will follow in India upon the departure of the English.’ This convergence of the views of Hitler and Churchill with regard to Indians is important. This validates the observation of Savarkar that one need not think of Churchill as a demigod because ‘he calls himself a democrat.’

Savarkar did support the national assertion of Germany under the Nazis. Golwalkar ‘Guruji’, the second leader of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), also looked at Germany when speaking about 'Race Spirit' though he never mentioned the Nazis. However, this admiration for the reassertion of Germany through nationalism after its defeat at the hands of Britain and her allies in the First World War was more a natural reaction of Indian nationalists than a stand arising out of an alleged bias for the Nazi ideology. It would have been better had the author brought out this aspect too.

For instance, when Golwalkar speaks about the German ‘Race Spirit’, it is neither in appreciatory terms nor is it related to a biological race. Instead for Golwalkar, the ‘Race Spirit’ that manifested in pre-war ‘modern Germany’ under the Nazis ‘perforce follows aspirations, predetermined by the traditions left by its depredatory ancestors’ who overran ‘the whole of Europe.’

None can write about Hitler and India without omitting Subhash Chandra Bose. Here too author walks the conventional take – that Bose had to use Nazis and that the Nazis were not very enthusiastic. The topic should naturally bring in Himmler. The book does speak of him – mainly with respect to his Tibetan expeditions which wanted to prove some fancy Nazi notions of history. Needless to say, the expeditions failed to achieve their objectives. However, Himmler’s role as the major negotiator with Bose deserves more attention.

In this regard, one should say that Bose in Nazi Germany (Romain Hayes, Random House, 2011) does a more thorough job. Whatever Hitler’s views were on India and Indians, Nazi Germany as such wanted to make use of anti-British Indian freedom movement to create as much headache for the British as possible. While for Purandare, Bose should be approached with caution and veneration, Hayes has no such compulsions. After Himmler received Bose in Nazi Germany, it was Goebbels who next met Bose. In this meeting, Bose strongly criticised Gandhi.

An important omission in the book is Sri Aurobindo. To be fair to the author, though the book is titled Hitler and India, the emphasis seemed to be more on Hitler’s views on India – particularly his hatred for Indians and his deep hatred for them as an inferior race. Yet, as the author had dealt with Savarkar, Hedgewar, Moonje and Golwalkar, it should only be fair that he should have also dealt with Sri Aurobindo.

Sri Aurobindo, venerated as Maharishi, was more central to the RSS worldview, particularly in their conception of Bharat Mata, than even Savarkar. Aurobindo squarely rejected Nazis and considered them demonic dark forces. When a disciple thought that Nazi persecution of Jews was because of the perception of their betrayal of Germany in World War I , Sri Aurobindo vehemently rejected it. This was in 1938. Sri Aurobindo stated:

Even Nehru, who because of his international travels actually knew the ideological positions of Western polity better than he understood Indian reality, lacked such a clarity. In fact, Nehru got himself invited to Nazi Germany. When it came to Arab-Nazi collaboration against the Jews, again Nehru balked, going to the extent of saying to the Zionist envoy that he would not mind supporting Arabs even if they and Nazis supported each other.

On 17 May 1940, Sri Aurobindo was pointed out that more than half of the Ashram residents were hoping for the victory of Hitler because of their anti-British stand. He was not happy about this. The Mother, his spiritual collaborator, declared the very same morning that a pro-Hitler stand was betrayal of Sri Aurobindo.

The way Nazi ideologues viewed Hindu 'caste system' has been brought out by the author. While Hindu reformers, from Veer Savarkar to the bitter-most critic Dr Ambedkar, held that the varna system was originally not birth-based, the Nazi ideologues held the opposite view.

Alfred Rosenberg an aide of Hitler took a special interest in India. ‘The rich, blood-based meaning of Varna was entirely lost,’ according to him and it had become ‘only a division between technical, professional and other classes, and has degenerated into the vilest travesty of the wisest idea in world history’. The 'traditionalists' in India who detest every Hindu reformer from Swami Vivekananda to Dr. Ambedkar and uphold birth-based varna would do well to look at their faces in this Nazi mirror.

On the whole the book is a welcome addition in popular history writing and research outside the academia in India. The previous book on Savarkar by the author brought out a fascinating picture of the freedom fighter. The present book, while definitely a scholarly work, follows a conventional path. Though it is timely, for it awakens a new generation of Hindus, some of whom are Hitler-admirers, to the harsh reality of the German dictator. Although, the book could have broadened its scope by including the whole wide range of Hindu responses to Hitler.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest