Books

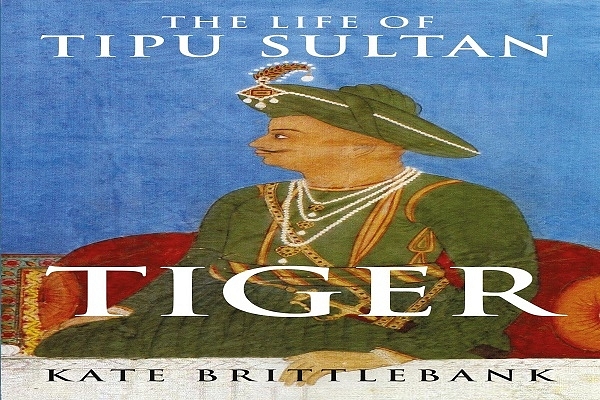

Who Was The Real Tipu? Review Of ‘Tiger: The Life Of Tipu Sultan’ By Kate Brittlebank

- The controversial figure of Tipu Sultan is sought to be understood by the author in Tipu’s own terms, or how he looked at himself, shorn of the labels of ‘tyrant’, ‘freedom fighter’ or ‘oriental despot’ that were thrust upon him by others.

Image Source: Amazon.in

Tiger: The Life of Tipu Sultan is a simply written and accessible book about Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore from 1782 to 1799, who was killed by the British on 4 May 1799 during the latter’s battle for the conquest of Mysore.

The controversial figure of Tipu Sultan is sought to be understood by the author in Tipu’s own terms, or how he looked at himself, shorn of the labels of ‘tyrant’, ‘freedom fighter’ or ‘oriental despot’ that were thrust upon him by others.

Tipu inherited his kingdom on the death of his father, Haider Ali, who had served the Wodeyars and later usurped the kingdom, maintaining the fiction of ruling in the name of Krishnaraja Wodeyar II. The Dowager Maharani never accepted this de facto rulership and fought against Haidar and Tipu till the latter’s death in 1799.

India was then a seething cauldron of conflicting interests; the French, the English, the Marathas and Haidar and Tipu all fought periodic battles in an ebb and flow of changing fortunes. The complexity and changing nature of the alliances are clearly brought out in the book. Its main focus is not really to present the historical facts of the time but a study of Tipu, the man, and how he understood himself and related to the circumstances that surrounded him.

Brittlebank tries to clear away the myths surrounding Tipu and provide a more authentic picture. The book itself consists of six chapters that focus on the construction of the myths, the chronological delineation of the events of his reign and a final chapter on the man himself, a personal look beyond the historical personage.

The first chapter promises well; the reader expects the lifting of the veil of myth to see the reality, as it deals with the making of Tipu’s image by the British. The events of Tipu’s reign are described in a sympathetic tone, explaining the religious and linguistic bigotry, the mass killings and conversions as political necessities of the time. She describes conversions and the forced transfer of populations from Kodagu and Malabar but explains it away as chastisement. The ‘chelas’, or slave troops, made up of those forcibly converted to Islam, like the janissaries of the Ottomans, are also mentioned almost in passing. Kannada was replaced with Farsi, names of places were changed to new Farsi ones (sometimes the same name was given to two different places). A new lunisolar hijri calendar was introduced with mixed administrative results.

In one of the most infamous acts of his reign, the Mysore library was destroyed and the books used as fuel for the stables. He has himself boasted of forcibly converting lakhs of people to Islam, but Brittlebank explains all of it away as the exigencies of politics and in line with the way rulers behaved at the time. As proof of his religious tolerance, she cites his donation to the Sringeri Math. That has also been interpreted as a political expediency to buy the support of the large Hindu population while Tipu himself was in an enfeebled state.

The crusades between the eleventh and the fifteenth centuries are seen as a reason for the hostility between Christianity and Islam and the reason for British attempts to paint him as a tyrant. The people of southern India are, however, portrayed as happy to be ruled by a minority-Muslim ruler, whose family’s entry into the country went back only two generations.

Brittlebank spends a great deal of time on the royal symbol of the tiger, which she says resonated with both Hindu and Muslim subjects and helped an insecure Tipu to establish his legitimacy.

There is a description of Tipu’s fascination with modern technology of the period and attempts to use them in his kingdom. European methods of fighting and military management were appreciated and adopted by him.

The description of Tipu, the man, is based on a number of sources, although there is more of conjecture than can be reasonably accepted in a history book.

One of the sources was Tipu’s book of dreams. He wrote this in Farsi, a language he loved and was proficient at, in his own hand and in complete privacy, and the papers were found in the royal latrine at Srirangapatnam after the British defeated him. He had become even more religious and dependent on omens and signs after his defeat of 1792 and desired to appease his God and become a good Muslim. He wrote down his dreams and interpreted them in a deeply religious light.

On the basis of a dream he had about a man who had changed into a woman, the author has drawn the conclusion that he ‘liked’ women. To say that he had a positive attitude towards women on the basis of one dream where he says he would speak softly to a woman seems like theorising on the basis of insufficient data. It ignores the realities of the number of female slaves, wives of defeated enemies and scores of women of his kingdom who merely took his fancy and were in his harem; 601 women were found in his harem after the fall of his kingdom. Although Brittlebank informs us that there is no evidence that he mistreated them.

Moreover, a full description of that dream as narrated by him (not in the book) reveals that he interpreted it as the Marathas being weak women in the guise of men and, therefore, eminently defeatable - surely not very good evidence for the author’s thesis about Tipu’s attitude towards women.

On reading the original book of his dreams, quite a few of them seem to be about the massacre of ‘nazarenes’ and burning down of their houses and thinking of them as cows in the guise of tigers and, again, therefore easy to defeat. Or about the defeat and extermination of the unbelievers or Hindu kafirs, the waging of jihad, and the triumph of the Muslims. The author has drawn very different conclusions in her analysis.

There are only five references cited at the end of this book, apart from the author’s own book on the subject published in 1997. On a topic as controversial and weighty as Tipu, this appears to be insufficient. In this light, one cannot say if she is aware of the writing on Tipu in languages other than English; for instance, Kannada, which would surely have yielded some balance to the presentation.

For the Indian reader, the myth-making in India with the many controversies around casting Tipu Sultan as a freedom fighter and a ‘secular’ king are of greater importance. Bhagwan S Gidwani’s ‘historical’ novel, The Sword of Tipu Sultan, or Girish Karnad’s play, The Dreams of Tipu Sultan, have generated much discussion around these themes. Brittlebank has not discussed these issues.

In actual fact, the current myth-making around him, done by India after 1947 - which is intertwined with domestic politics - is completely ignored. This leaves the reader looking for contemporary Indian insights short-changed, although the person who wants post-colonial insights may be happier.

For those interested in history in more than a cursory fashion, Tiger is oversimplified; for others who want a simple and quick read, it will allow access to the subject, but more reading will be necessary to get a better grasp of it.

In closing, the book reads like a hagiography of Tipu in an admiring tone; the myth-breaking turns into a fresh bout of myth-making.

Also Read:

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest