Business

Der Aaye, Durust Aaye. How Air India Sale Marks A Huge Shift In Modi Government's Thinking

- Modi has come late to the privatisation party, but he has arrived with conviction. That’s a huge plus.

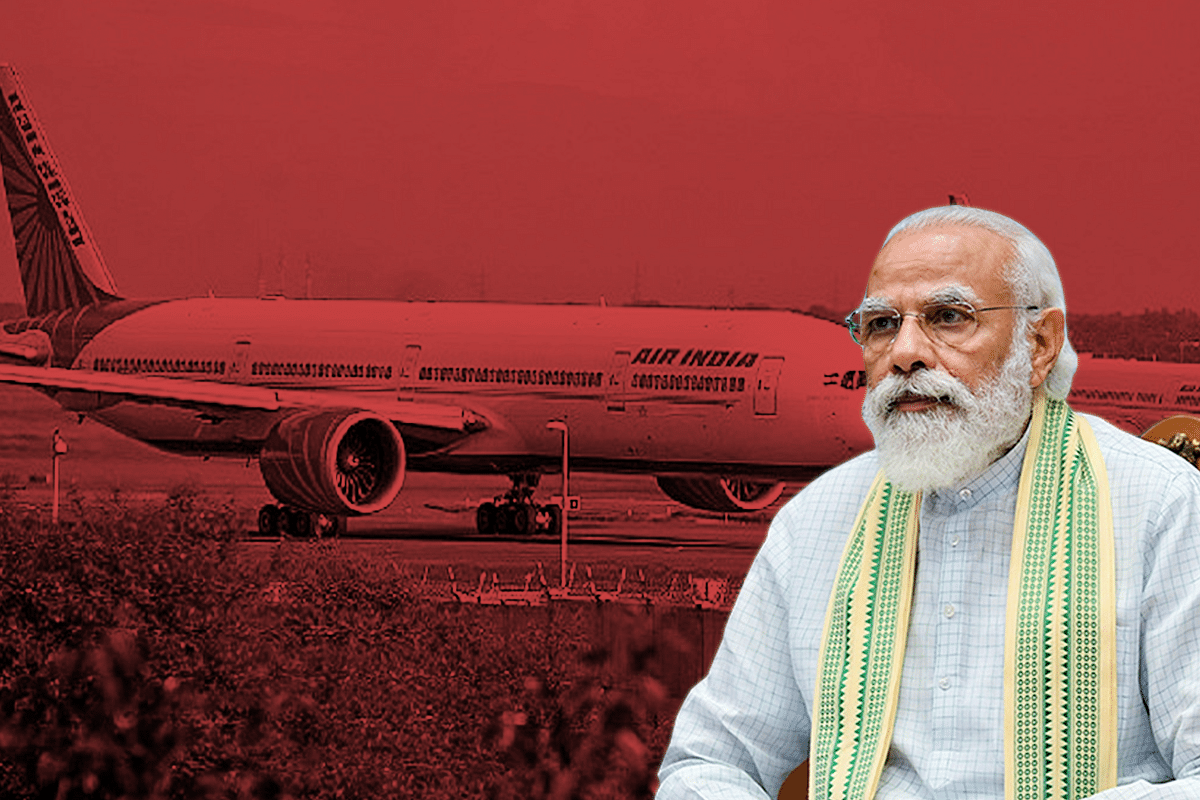

Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The political and economic significance of the Narendra Modi government’s privatisation of Air India cannot be overstated. It has taken more than three years to come to this stage, and will take some more months of navigating the regulatory and lender approval processes before the flailing airline will legally become a Tata enterprise. So, finger-crossed.

The real significance of this privatisation deal is not the sticker price, which is just an abstract number, not real cash. The Rs 18,000 crore winning bid of the Tatas includes just Rs 2,700 crore in cash, with the rest being debt that goes with the airline. But even the Rs 2,700 crore is not the net amount coming into the government’s coffers.

Once we exclude the Rs 15,300 crore debt built into the price, Rs 46,262 crore of the airline’s existing debt that got transferred to an asset holding company, Rs 15,000-crore-and-odd of dues the airline owes to suppliers of fuel, fleet lessors and unpaid dues to employees (which the government has to clear by the time of the handover), it is clear that the government effectively paid money to get the airline off its hands.

Politically, this is a difficult sell, but that is the greatest significance of this privatisation. It represents an inflexion point in the government’s thinking where it is trying to stave off future demands on taxpayer funds and acknowledging – without actually saying it – what Narendra Modi said as far back as in 2012, before he became Prime Minister, and which he reiterated earlier this year: government has no business being in business. He has taken nine years to translate this belief into reality.

That is the true significance of the Air India privatisation deal, which marks the formal crossing of the Lakshman Rekha that politicians have drawn for themselves – but with the reverse objective in mind. The objective of this invisible Lakshman Rekha was not to protect the Sita of fiscal rectitude, but to give political and bureaucratic Ravanas space to hijack public funds for their own nefarious private purposes, including patronage powers.

The second big significance of the Air India privatisation is that it now clears the road for future privatisations on a different basis: it won’t always be about making money for the exchequer, but to get the government out of some businesses that are not strategic to it and making them more efficient. Thus, selling off some banks, insurance companies and even some quasi-defence units to the private sector will become feasible politically now that the Lakshman Rekha has been crossed.

Third, the benefits of this crossover in political thinking will be a huge reduction in the power of the state, and its ability to be both player and referee. As long as there are public sector units being run by ministries, the imperatives of policy-making are compromised by a conflict of interest. For example, how can aviation ministry or regulator be player-neutral if one major company is owned by the government? Ditto for telecom or banks or insurers.

While it is not important to divest all public sector units merely because of the likely conflict of interest in policy-making and regulation, the next logical step in reducing these conflicts is to transfer ownership of public sector companies from nodal ministries to a holding corporation with its own independent board. The job of the nodal ministry, any ministry, is to make policy not to run companies. The Air India divestment brings this clarity once more to the policy and regulatory spaces, and must be extended to other areas which have big and influential players in the public sector, including telecom, banking and insurance.

Fourth, with the Air India sale, and assuming privatisation gathers pace based on this experience, another one of Modi’s pet thoughts will finally take shape: minimum government, maximum governance. Given the rapid build-up in government spending over the last decade, both before and after the Covid pandemic, observers were wondering what Modi really meant by minimum government. Till privatisation began, it probably meant that middlemen and Delhi’s huge paraphernalia of fixers and agents will be dispensed with. But with many companies about to be sold off – Bharat Petroleum, Shipping Corporation, BEML, etc – governance can take precedence as the commercial role of government shrinks steadily.

Der aaye, par durust aaye. Modi has come late to the privatisation party, but he has arrived with conviction. That’s a huge plus.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest