Commentary

The Contrarian Political Currents of Karnataka

A precursor to the upcoming assembly elections

There is overwhelming electoral evidence to suggest that 21st Century Indian democracy is essentially about governance and development politics, rather than about caste or identity. Since the dawn of the new millennium there have been 77 electoral battles, both nationally as well as at the state level, and a whopping 71 of them have managed to produce a positive mandate of giving either a majority or near majority to one of the party or group. What it means is that 92% of all Indian elections since 2000 have produced positive results.

The message is loud and clear from the Indian voters to their political leaders; “we will give you majority and stability, you deliver on the governance quotient”. This is indeed an amazing evolution from the politics of the 90’s whence the Indian voter tended to vote purely on the basis of identity, which invariably led to fractured mandates. Today, even highly mandalized Hindi-heartland area has started producing unanimous verdicts cutting above caste and ethnic divisions.

Apart from the 2004 national elections, the erstwhile greater Bihar region has been the only major exception to this rule of electoral majorities; Bihar in 2005 and Jharkhand in 2005 & 10. Beyond this, the list of electoral instabilities is almost totally empty, but for a very strange south Indian companion – Karnataka.

An Indian political antithesis known as Karnataka

Karnataka has always been a state that has swam against the political tide prevalent in the country at any given time. In the mid-late 70’s when the whole of India was swept by the JP wave, Karnataka was one of the rare exceptions that still reposed faith in the Congress party. So much so that a down and defeated Indira Gandhi travelled all the way to this southern state and won a by-election in Chikamagalur to return back to the parliament.

As a stark contrast, in the mid-80’s when India was grieving Indira Gandhi’s assassination and was giving an unprecedented majority to Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress everywhere, Karnataka chose to elect an upstart known as Ramakrishna Hegde and his Janata party (which was almost defunct everywhere else). Similarly, in 1989, when all of India was in a Bofors-wave and had turned totally anti-Rajiv, Karnataka chose to give an almost 2/3rd majority to the Congress party in the state.

In 1999 elections, following the Kargil war, when India was swept by a Vajpayee/NDA wave, Karnataka was once again an exception to the rule – elected a S.M. Krishna led Congress government. Then in 2004 & 2008-09, when the Congress party was on the path to revival all over India, it lost successive elections in the state. Thus today, when all over India, people are electing majority governments for better governance, Karnataka stands as almost a lone exception with deep-rooted political instability as the order of the day.

In fact, the electoral-political history of the state in the post-emergency era is a textbook of antithesis to the central theme of India. It wouldn’t be wrong to suggest that every election in Karnataka since 1975 has produced a contrary result to that of the corresponding Indian national election, take a look at the table below;

Data Source: Election Commission of India

Political fragmentation and instability

2004 saw an exceptional election in Karnataka’s political history. For the first time there was a three-way split in the voter choice, something unprecedented not only in the state but probably in entire south India. Even in 1983, when the state saw a coalition government for the first time, such fragmentation was unheard of (INC = 82, JP = 95, BJP = 18 in 1983).

In 2004, all the 3 principal players won identical proportions of assembly seats – 79, 65 & 58 by BJP, Congress & JDS respectively. This made it impossible to not only have any kind of stability but also for any party to have any kind of upper hand in government formation. Furthermore, even splitting any party in favour of another party was also extremely difficult as all three had mostly captured mutually exclusive vote in terms of region/caste/religion.

For instance, the BJP and JDS vote-banks were almost mutually exclusive – if the JDS core vote was that of Vokkaligas belonging to old Mysore, that of BJP belonged to Veerashaivas of North Karnataka. Similarly, if the Congress vote was that of minorities and marginalized sections belonging to the villages, that of BJP was essentially Hindu and urban in nature. Thus there was no incentive for the MLAs to quit their parent party’s and hop over to another, as there was inherent caste-regional antagonism involved. This was a classic case of fragmented polity, albeit it had come a decade late to this state.

This fragmentation continued even in the 2008 elections, when all the three parties more or less maintained their core-vote, but BJP managed to gain about 5% vote-share from the “others” to almost win the elections. Thus, in reality, the 2008 assembly elections of Karnataka did not see any path-breaking social-engineering or an alternate political reality; it was simply an amalgamation of “other’s” vote-share to the winning party.

Data Source: Election Commission of India

Future imperfect for Karnataka

- Classically, anti-incumbency should have helped the main opposition party tremendously, but the Congress party has shown remarkable strategic lethargy in the state to further augment political fragmentation rather than consolidation

- Congress party wants to win the upcoming assembly elections by default, but that won’t be easy with its current vote share of around 35% which can at best take its tally to 80 assembly seats; the party needs a 4%+ swing in its favour to get close to the majority mark

- Congress has never won Karnataka by polling less than 40% of the vote-share

- Due to its widespread political base in the state, Congress party needs higher vote-share than others to win elections, which is an inherent handicap. The widespread base of the party is apparent if one looks at the number of seats that the party forfeited its deposit in the last 2 elections vis-à-vis other parties. (see the table below)

Data Source: Election Commission of India, FD = Forfeited deposit

Epilogue:

The ruling group of Karnataka BJP is a pack of pessimists; that they lack the killer instinct is well known, but what is surprising is that they don’t have even a basic zeal to emerge victorious in the elections. Although state BJP leaders put up a brave front for public consumption, most of them concede privately that they stand no chance in hell of winning the next assembly elections in the state. Most Karyakartas have been told by their leaders to be prepared for a long spell in the opposition.

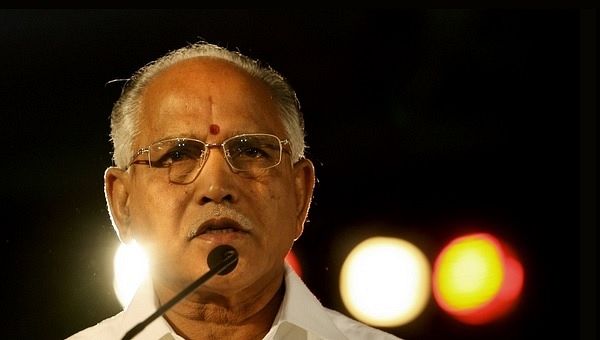

Many of the so called “leaders” of the Anant Kumar gang tell you candidly that it doesn’t matter if Congress or JDS come to power in state, it would be business as usual for them because their leader has great rapport with Congress & JDS leaders. “In fact, our works got stalled in the BJP government headed by BSY, so it is better that there be a Congress government in the state” avers one of those “leaders”. This is at the core of the problems for BJP in Karnataka. BSY has this incredible zeal to win at any cost and that translates into super-human efforts by the local Karyakartas. BJP minus BSY is simply an electoral non-entity that would crumble like a pack of cards.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest