Commentary

We are not as logical as we think

Many seemingly intelligent people often hold completely illogical or dogmatic views about certain issues. There are topics on which a person is unable to move beyond their initial opinion even when faced with overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

This is not about behavior derived from personal interest. When politicians defend their stance, often by making ridiculous arguments and accusations, it is a part of the political game to defend their party line or follow the laws of expedience. Sometimes even the media may promote a view, perhaps by presenting facts selectively, but it is for compulsions that are usually business related. Pressure groups and vested interests stick to their line of thought, since it is the raison d’etre of their existence. In each of these cases, there is a rational explanation for the behavior. However, when regular individuals with no external compulsions respond in bull headed or arbitrary ways, it is puzzling.

I had been pondering on this issue for a while. Then I read an article by Yale psychologist Dr.David Powell where he discusses cognitive biases. The answers finally began to fall into place!

Cognitive biases and how they affect us

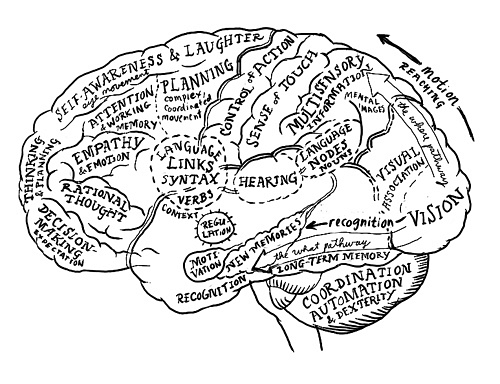

We all know that the human brain is a complex organ that helps us to think, reason and make sense of our world. What most of us don’t realize is that when our brain makes judgments or decisions, it often processes complex issues by using mental short cuts. These short cuts are simple rules (heuristics), which work well most of the time, but have their limitations. They create thinking glitches that result in deviations from rationality and logic. These glitches or cognitive biases drive our actions even when we are not aware of it. Thus, as Dr.Powell says, we may believe that our decisions are rational because they are based on careful evaluation of information, while in reality they are based on emotions, instincts and mental shortcuts

Availability heuristic: A common mental shortcut is that we tend to make judgments or decisions by relying on the most readily available information. If something comes more easily to mind, we assume that it also occurs more commonly, or that it is a more realistic reflection of our world. For example, we may believe that murder is more common than suicides, as murder is more widely reported, and the discourse on suicide is muted. In reality, suicide is the bigger killer.

Propaganda works on the basis of the availability heuristic. When an idea or word is highlighted over and over again, and it sticks in our brains. Once that happens, we are able to recall the information easily. Then, our subsequent judgment is based on what we remember from the propaganda, and not on complete data.

A good example of this bias is how many of us view Leftist policies as noble and pro-poor (at least in intent). This is because words like “human rights”, “progressive”, “inclusive development” etc have been co-opted by the Left, through years of repeated reinforcement. More atrocities have been committed by communists/socialists than perhaps all ideologies put together (Stalin, Lenin, Che Guvera , Mao, Pol Pot are just a few luminaries).Yet the Left pretends to hold a high moral ground, as most people are oblivious to the dark data. The fact that some people dare to dignify & justify the acts of supposedly “Gandhian” terrorists, and get away with it, shows the tremendous success of the Leftist propaganda.

Stereotyping: When we make difficult predictions, we use a person’s social group (race, ethnicity, gender, age, religion etc) as a frame of reference, to answer questions. For instance, when making assessments like, “Can I believe this person?” Or “Is he/she competent?” Our decisions are often based on social biases. In other words, we tend to automatically judge and label people without adequately analyzing the proof.

Some common stereotypes include the view that Rajputs are brave, Punjabis are flashy, Bengalis are intellectual, IT people are geeks, and so on. Our blanket labeling of a group then affects our responses to individuals from the group .In fact numerous studies have shown that a person’s social group has a bearing on the treatment they receive.

Let’s illustrate this point with an example. We know that Nobel Laureates have excelled in their field. Therefore we assume that they are exceptionally intelligent. Once we stereotype this group as being exceptionally intelligent, we look up to them and assume that everything they says is correct. This is why when economist Amartya Sen has a view, we give credence to his ideas without examining the basis for his claims. When he speaks on topics like the controversial Food Security Bill (FSB), we blindly assume that he knows what he is saying.

However, our perception may be wrong. In a statement on the FSB, Amartya Sen claimed that a thousand children were dying per week because the bill was not being passed in parliament, but there is no statistical evidence to prove his point. When Arvind Panagariya, another well-known economist, challenged the statistics, Mr.Sen provided no explanation for his numbers (and has not done till date). But many still believe that he must be right since he is a part of the “exceptionally intelligent” Nobel group.

The halo effect: When we judge a person, we often tend to over rely on one personality trait, to view an entire person. So, when we see a desirable trait, we imagine many other positive traits, and our feelings override logic. Thus, if a person is charming, we tend to believe that he/she is also generous and trustworthy. Similarly, if a politician is good looking, we may assume that he/she is also capable and intelligent.

The halo effect is one of the reasons why movie stars who stand for elections often win in India. The halo of their onscreen image fosters a sense competence, even though their abilities as administrators or legislators are untested and unknown.

There are also cases when the halo of a person gets transferred to a person/s by association. For instance, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s name is associated with sacrifice and trust. In many parts of India, the halo associated with his name is transferred to people who are not even remotely related to him, but happen to bear his surname. The citizens who idolize or vote for them may not have any idea of the current deeds, policies or views of these Gandhis, yet the name fosters feelings of familiarity and trust through generations.

Bandwagon effect: People have a tendency to follow the beliefs of others and do something just because others are doing it. They jump onto the bandwagon regardless of the underlying evidence. This is due to the fact that humans are social animals who like to conform, and derive information from other individuals. This trend is seen in many fields; once a product becomes popular, lots of people want to buy it. When a fashion becomes a rage, more people copy it. In politics, this effect is evident when people switch sides to support a candidate, party or movement that is seen as likely to win.

A good example of the bandwagon effect is how Manmohan Singh turned from being a hero to an impediment, almost overnight. Until a few months ago, inspite of mega scandals plaguing the UPA government, Mr.Singh was considered untouchable. Even when people wrote about his weak leadership and silence in the face of open loot, they prefixed his name with an “honest” tag.

Then suddenly things changed. Facts which had always been in public domain seemed to become glaring. Mainstream media publications including The Outlook and India Today decided that the “honest” tag, which had been bestowed so generously and determinedly, did not seem so appropriate after all. Their articles opened the floodgates for many others to join the bandwagon and criticize the previously feted Prime Minister. Then, citizens who swore that the PM could do no wrong suddenly started finding his flaws. Thus the tide began to turn from one extreme to another, even though there was very little information that was new.

Confirmation bias: All of us have a tendency to filter information based on our existing views & beliefs. This was proved by a series of

experiments in the 60’s, which showed that when people gather information, they remember things selectively and ignore alternatives. This bias especially shows up in emotionally charged or sensitive issues that pertain to belief systems such a religion or personal values. What is interesting is that these beliefs often persist even when the initial evidence for them is removed, or compelling evidence is presented to counter it.

For instance, there is a lobby that actively propagates the myth that online abuse is somehow the domain of right wing males. This view has been repeatedly rebutted with evidence to show that it is a general problem involving of people across ideologies. In an earlier article I had written extensively on this issue (See Understanding Abuse On Social Media). However, some people only seem to notice ‘right wing’ abuse and filter out the rest.

Conclusion:

The main point derived from this survey on cognitive biases is that you (and I) are not as rational as we believe. Moreover, even the most “rational” among us can get systematically blinded by propaganda of various kinds. This is especially true when a story is repeated over & over again, and is embellished with more & more detail to make it vivid. Media unfortunately plays a prominent role in this. As the process gets underway, untruths & spin doctoring get mistaken for the gospel truth. Even when confronted with facts to the contrary, the mind then chooses to doggedly hold to the earlier false beliefs, all in name of logic, rationality and justice.

Note that all political elites across the world have known of these biases, and have used them through the ages to control people’s views. The rise of social media is a threat to them as their propaganda is now being easily challenged through alternative narratives.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest