Culture

A Chronicle Of India’s Dying Professions

- ‘The Lost Generation’ by Nidhi Dugar Kundalia serves to document the history of some of the dying professions of India, while churning up a good measure of nostalgia and even desolation writes Urmi Chanda-Vaz.

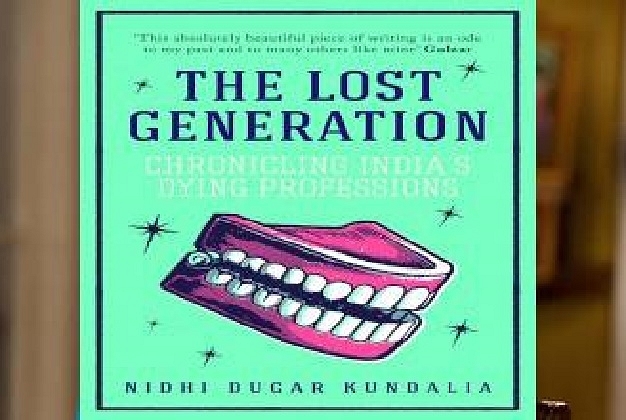

Book Cover

No respectable lover of Indian history and culture can walk nonchalantly past the aisle of a bookstore when the title of a certain book on a certain shelf says The Lost Generation: Chronicling India’s Dying Professions. And if the title of the book doesn’t convince you enough to buy it, a very cute illustration of a pair of dentures and a testimonial by Gulzar saab on its cover will.

Nidhi Dugar Kundalia definitely shows her journalistic penchant for attention-grabbing ‘headlines’ on the cover of her debut book. In fact, her skills as a journalist are perhaps what made this book possible. One must laud her for her extensive research, an eye for detail, and objectivity right at the outset.

The book chronicles 11 of the old India’s dying professions, including ‘The Godna (tattoo) Artists of Jharkhand’, ‘The Rudaalis (mourners) of Rajasthan’, ‘The Genealogists of Haridwar’, ‘The Kabootarbaaz, (pigeon rearers) of ‘Old Delhi’, The Storytellers of Andhra’, ‘The Street Dentists of Baroda’, ‘The Urdu Scribes of Delhi’, ‘The Boat Makers of Balagarh’, ‘The Ittar Wallahs of Hyderabad’, ‘The Bhisti Wallahs’ (water carriers) of Calcutta’ and ‘The Letter Writers of Bombay’. One runs out of breath just reading the number of places in the index; imagine the extensive traveling the author must have had to do to put it all together.

The author picks an interesting mix of places and professions from the vastness that is India and proceeds to offer a slice-of-life from each of those obscure grounds. Some places are truly geographically obscure, such as the forest hamlets of Jharkhand or the far-flung villages of Rajasthan. But the others are obscure from our collective vision, even in plain sight. The author travels in a time machine as it were, when she goes to these places looking for the last practitioners of dying practices.

One of the toughest places, by her own admission, was the Naxal-infested tribal village near Ranchi where she sought to interview a Godna artist and some tribal women who get these ritual tattoos done. In this, as in all other chapters, she posits an interesting all-round account of the profession. She mentions the earliest historical records, the associated myths and superstitions, the socio-economic conditions and its cultural implications.

Sample this:

The number of details included makes the book credible,and not boring. Her research is sewn effortlessly into the narrative, and her efforts are clear to see in the impressive bibliography at the end of the book. Her sensitivity to local customs and the importance they hold for these micro societies is also worthy of admiration.

Apart from the professions, the author is also an astute observer of people. These fading professionals come alive in the pages of this book, where some zealously protect their ancestral crafts and some count the days listlessly waiting for their curtain calls. Whether it Feroja, the rudaali bemoaning her paltry income; the Burrakatha storytellers of Andhra weaving together mythical and political stories; or Anil Sood, the most famous kabootarbaaz of Delhi, waxing eloquent about his ‘babies’, each person and his account is believable and human.

But what strikes you most is the nostalgia that hangs thick over all the stories. As one reads of a time when these professionals were not only important but also indispensable to the society, one cannot help but feel a jab of pity in one’s chest. The poverty and desolation of most of these people is so compelling that one almost feels guilty for having progressed and rendered them redundant.

This is how the author effectively laces fact with emotion in this book, and keeps her readers hooked. Sometimes, she also veers towards the poetic in a bid to juxtapose beauty with grim reality, but she is clearly a better journalist than a poet. When she starts an account with a description of the scenario, her metaphors seem forced and her imagery crowded. Too many sights and sounds find themselves cramped into a paragraph such as this:

But beyond these indulgent tropes, the book is definitely a fantastic first attempt. It does well what it promises to do by painting a powerful, if not pretty picture of a generation of people whose lives and livelihoods are slowly fading into oblivion. We can only read and nod our heads at the inevitable.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest