Culture

[Long Read] Book Review: Aravindan Neelakandan's Latest Is A Comprehensive, Path-Breaking Hindutva Classic

- This book is a consolidation of the many profound and overarching ideas, themes and insights that Aravindan Neelakandan has conceived and expressed through his articles, talks and interviews over the years.

- It would not be a surprise if some readers find the book encyclopaedic.

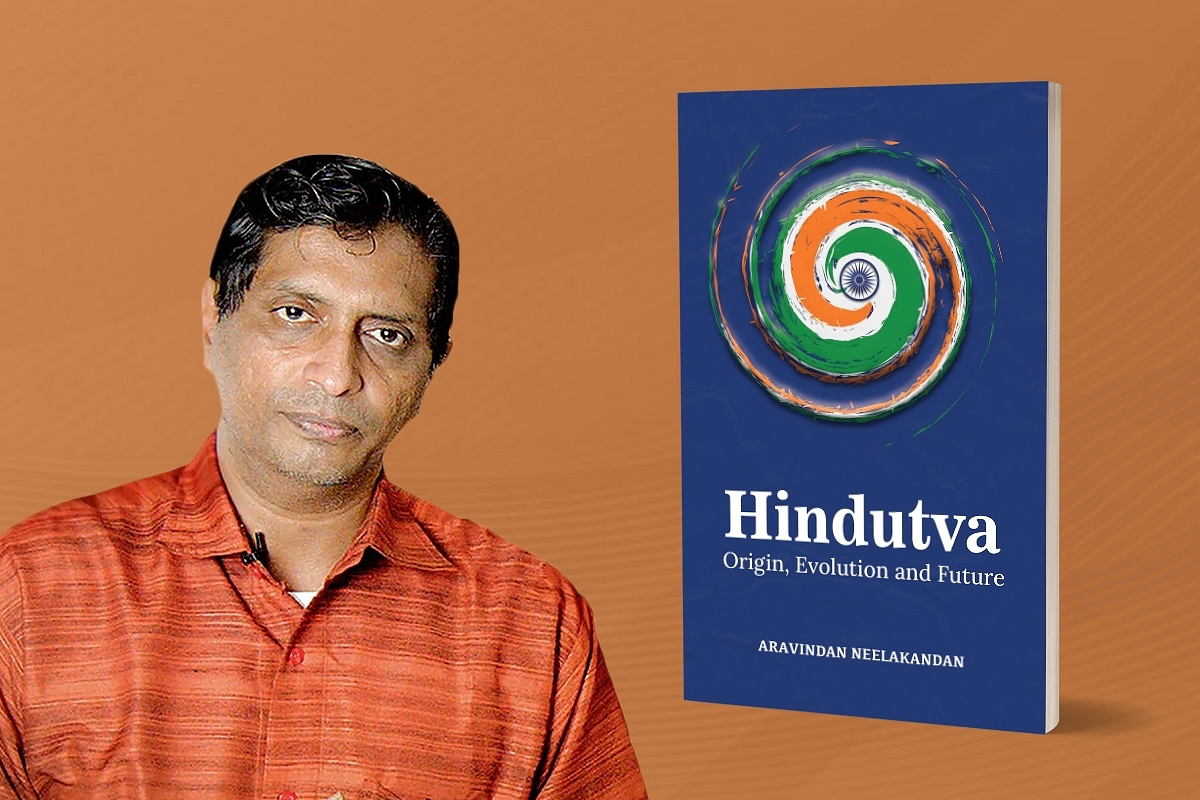

'Hindutva: Origin, Evolution, and Future', and its author, Aravindan Neelakandan.

Hindutva: Origin, Evolution, and Future. Aravindan Neelakandan. BluOne Ink. Pages 816. Rs 967.

Hindutva: Origin, Evolution and Future, by Aravindan Neelakandan (2022) is a fascinating and absorbing book in many ways. Discerning readers would readily find it to be the most comprehensive, multi-faceted, multi-dimensional and scholarly exposition of the phenomenon called Hindutva in writing so far.

“Hindutva is often studied similar to other extreme right-wing ideologies. However, the thesis presented in this book is built on the strong foundation that Hindutva is not an ideology but a process—a historical-civilizational process” - this the premise the author states right at the preface, and it naturally follows that “one must jettison the usual academic and political frameworks to study Hindutva and Hindutva organizations”.

This voluminous book does offer a refreshing alternative framework to study and explore Hindutva that has not been so succinctly presented so far, despite the fact that so much has been already written on the subject, both positively and negatively. This book is indeed path-breaking, in that sense.

The opening chapter of the book, ‘The Origins’ starts not from Veer Savarkar or 19th century Hindu renaissance as one would normally expect, but from a neuro-cultural narrative set in pre-historic times.

The evolution of religious experience in humans is analysed, introducing the concept of “bicameral mind” proposed by the psychologist Julian Jaynes. The unique civilizational direction taken by the Vedic ritual and spiritual expressions in ancient India is explained through that.

This ‘Hindu consciousness’ is then contrasted with the alternate path taken by the early Persian culture that was contemporaneous with Vedic culture, and with how that culture birthed the monotheistic and prophetic religious tendencies in West Asia.

In this process, the book highlights the connection of the word ‘Hindu’ with the Vedic Soma ritual and the moon, called Indu and Soma in Sanskrit, and links that to the rivers Sindhu and Saraswati, thus giving a sound spiritual and philosophical grounding to the word, along with the well-known geographical connotation (pp. 15-16).

The unique and integrative nature of this Hindu consciousness throughout history, right up to the period of British Colonialism and the freedom struggle is illustrated next. How the modern Hindu savants defined the Hindu identity in diverse, yet uniting ways is brought out by citations from Swami Vivekananda, Gandhi, Veer Savarkar, Ambedkar and others.

So far, this historical narrative of Hindu consciousness is on familiar lines. Then the book takes a leap and extends the concept of Hindu consciousness to “Universal Mission” and “Universal Ethics” referring to Sri Aurobindo and the idea of ‘universal experience of Absolute Unitary Being (AUB)’ proposed by Andrew Newberg, a scientific researcher working in the field of Neurotheology (pp. 37-40).

This point is very much debatable, this reviewer feels. The upcoming academic fields of Neurotheology and Consciousness Studies tend to borrow many foundational ideas from Hindu philosophical systems, especially Advaita Vedanta and present them with high sounding academic jargons, like AUB. Given this, the better course for the Hindutva discourse is to rightly claim and assert the uniquely Hindu nature of these insights, despite their universal appeal and validity, and not fall into the lure of the tendency to universalise the Hindu philosophical insights beyond a threshold.

This is borne out by the theme of the very next chapter on Bharat Mata and Akhand Bharat, the “two images central to any discussion on Hindutva” (pp. 46). It is obvious that these images are specifically located in a geographical and cultural context, far from being universal.

The book traces the roots of the stirring image of Bharat Mata as she is perceived today all the way back to the Vedic goddesses. Along with benevolent mother goddesses Ila, Bharati and Saraswati, the connection to Nirrti, the “negative” goddess in her fierce aspects is also brought out beautifully. This part of the book is a literary delight, as it navigates through the poetic visions of the Pan-Indic Goddess as seen in the Vedas, Mahabharata, Tamil epic Silappathikaram, Buddhist texts, tribal traditions and Bhakti hymns right up to the times of Ananda Math of Bankim and the modern poetry of Subramania Bharati.

How the sword-wielding Goddess inspired the Hindu heroes throughout the ages, heroes like the Vijayanagar commander Kumara Kampana, Chhatrapati Shivaji and Guru Gobind Singh is narrated evocatively (pp. 62-68).

This discourse on Bharat Mata can be considered as the most authentic and robust rebuttal to the finicky and motivated theories from the Marxist historians like Irfan Habib and Nehruvian writers who attempt to portray Bharat Mata as a modern idea borrowed from European sources and thus colouring the indigenous-rooted Indian nationalism as inspired from outside.

On Akhand Bharat, the author firmly establishes that the Hindutva conception of it is nothing of an “Expansionist or Imperial fantasy”, but an integrating vision that paves the way for harmonious, realistic cooperation on the ground and institutions like SAARC. The Akhand Bharat narrative in the book is well balanced and moderate, though grounded in the idealism of the Hindu leaders of the Partition era and the RSS (pp. 89-100).

****

The next two chapters of the book squarely address two of the most provocative and controversial topics - Cow and Caste.

The chapter on cow illustrates the pan-Indic nature of cow protection and cow worship by citing wide-ranging southern Indian traditions, perhaps to clear the prevalent skewed notion of associating the ‘Gau Mata’ largely with the North.

The ecological ramifications of cow slaughter are brought out through the comparison of the extermination of the bison, a “sacred animal” of the native tribes of Americas, in a compelling secular argument in favour of cow protection (pp. 116-117).

In a section interestingly titled as “Golwalkar, Karpatri and Kurien”, the author shows how there was a total national convergence of opinion in favour of banning the cow slaughter among the warring political and ideological camps in post-independence India right up to the 1960s and then how it got be perceived as a “communal” demand later. From this idealist standpoint, this chapter also outlines the hard problems in sustaining the cow protection culture in India, given the reality of mechanized agriculture, industrial dairy farming etc.

“With the industrialized high-energy consuming West having to move away from the meat-based diet because of ecological compulsions, the breaking of beef-taboo in Indian food culture can easily make India another South America-like beef exporter to the West. But it will ultimately create ecological disaster for India” (pp. 141). With such a serious cautionary note, one would expect a discussion on the rising beef exports from India in the recent years under the Modi government. But it does not go into that topic.

The chapter ends with a concerning note on the Hinduphobic “cow-lynch” labels that the global narrative creates. This reviewer thinks that this is not a wanton skip-over by the author not wanting to question the policies of the Modi government in this regard, but because the discussion on the beef exports problem is quite complex and is beyond the scope of this book.

With the dominant academic and media narrative on Hindutva associating with casteism directly and racism indirectly, the next chapter is solely devoted to debunking these arguments, and to inform the reader about the great accomplishments in social emancipation spearheaded by modern Hindutva leaders and organizations.

The author shows how the Hindutva leaders have consistently pointed out the total incongruity of interpreting the Indian castes based on Aryan race theories. “Aryan home theory is not central to the Hindutva discourse. While it is true that Hindutvites would be really happy if the Aryan invasion/migration theory is proved wrong.. In fact, Hindutvites claim that there is no such race called Aryans. To their credit, indeed, no anthropologist really talks of an Aryan race”, asserts the author quite correctly, contrary to the popular perception (pp. 154-155).

The glorious saga of the unsung Hindu nationalist leader Dr. NB Khare in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, which is no less in impact compared to Gandhi, is brought out in good detail (pp. 158-162).

The author points out how the Hindu Mahasabha and RSS both took strong positions against untouchability and spearheaded grass-root level social emancipation programs. The phenomenal work done by Hindu Sangathan leaders like Barrister M.R.Jayakar, Sitaram Keshav Bole and Swami Shraddhananda in these spheres is discussed in good detail, puncturing the false propaganda of some motivated historians and pamphleteers accusing Hindutva of harbouring and nurturing casteism in the Hindu society.

Elsewhere in chapter 6 of the book, Guruji Golwalkar’s evolving views on Jati that culminated in him saying, “the perturbed social system must be put to end here and now and should be destroyed root and branch” referring to the Varna Vyavastha, is discussed in detail.

This was the trigger for the historic 1969 Udupi VHP conference where Hindu Dharmacharyas passed a resolution against untouchability (pp. 345-351). Balasaheb Deoras, Guruji’s successor in the RSS took it to the next stage of “Samarasata” discourse, openly calling for the Hindu society “to emulate the Jewish principles of scriptural reinterpretation based on the modern context” in the context of texts like Manu Smriti. This internal conviction inside the Sangh Parivar was responsible for some unprecedented political and social transformations in the country, like the “social engineering experiments” involving BJP and BSP in Uttar Pradesh, the book points out (pp. 359).

On the issue of caste-based reservations spiralling beyond the original agenda of social justice, Sangh appears to be more of a mute spectator now. It does not want to risk saying or doing anything when the perverted politics around caste reservations is causing deep divides and feelings of bitterness in the Hindu society. This is an important and pressing social problem affecting the vitals of Hindutva. But the book does not delve on the Sangh stance or the lack of it on this sensitive issue.

The Sangh-inspired organisation Tantra Vidya Peetham of Kerala making “Hindus of all castes to be temple priests” project a reality, without any major social opposition or violence is given as a case study by the author (pp. 362-365). This is indeed a good example on how such lasting religious reforms can be implemented without uprooting or disrespecting the traditions but transforming and democratizing them. But this is an area where Hindutva organisations are better advised to respect the local customs and to be very patient, instead of applying such reforms as a general rule, with one broad stroke.

In many regions of India where hereditary priests serve in the Agama-ordained or Kula-Devata temples, the local Hindu communities are respectful of those traditions and may not want the “temple priest” reform at all. This is more so, given the fact that even the hereditary priests come from different castes already.

The Sabarimala controversy of the 2019-20 is a case in point where Sangh, respecting the overwhelming sentiments of the local Hindus in favour of the prevalent tradition had to reverse its earlier stand which it had considered “progressive”. The book could have included this episode to highlight how Sangh is adaptive and is willing to go on a course correction on such matters.

The chapter “Science and Hindutva” is an absolute gem and bears the signature style of Aravindan. It starts with recognizing the tendency among Hindutva groups and individuals to create and propagate a myriad of pseudo-scientific claims like “NASA satellite stopped by Saturn Yantra” etc. under the moniker “Cargo Cult Hindutva”.

The author laments about a similar tendency to foolishly attribute unsubstantiated past glories to ancient India, even while being utterly ignorant of real scientific achievements. The example of peddling nonsensical narratives involving “God Particle” and “Shiva, the god of destruction”, unaware of the fact that the so-called God Particle, the Higgs Boson is named after the Indian scientist S N Bose, its inventor, is notable in this regard (pp. 417).

Then, some shining examples for true Indian Science discourse are given – Prafulla Chandra Roy and C.K Raju. The Leftist propaganda of Sangh being anti-science is debunked with facts. The pioneering initiative of Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) under Dr Murali Manohar Joshi of the BJP, during his tenure as a minister in the 2001 NDA government is dealt in detail.

Its great successes in stopping many international patent applications on herbal formulations of Indic origin is highlighted (pp. 434-439). The case study of Science India, a magazine run by the Sangh-inspired NGO Vigyan Bharati is presented to showcase the kind of genuine science popularisation culture practiced by Sangh Parivar, free of any religious fundamentalism, superstitions or political bias (pp. 456-465).

***

The last chapter “The Harmonizing Samanvaya and Protection of Theo-Diversity”, is conceived to answer twin criticisms on Hindutva: One, that it is a homogenizing ideology that destroys all pluralisms within the Indic religions and in that sense, is different from, and even opposed to Hinduism. Two, it is an anti-Muslim and anti-Christian ideology rooted in the hatred towards these religions. It is elaborate and very well written.

Samanvaya being an integral part of Hindutva process from the beginning is explained with rich references – the overarching theme of harmony throughout Vedic, Upanishadic literature and then in Agama and Tantra based systems; Buddhism first condemning and later embracing Tantric practices; Buddhist temples incorporating Vedic architectural and sculpture styles; emperor Shalivahana developing respect for linguistic diversity.

The Marxist historian’s false narrative of ancient India rife with religious strife between various religious sects is refuted with credible citations from multiple sources. The general trend of harmony is elucidated and the stray cases of exceptions like Buddhist-Jain rivalry found in certain texts, the truth about Pushyamitra’s “persecution” of Buddhists, Shaiva-Jain rivalry in Tamil Nadu are analysed and explained in context. The author concludes, “What we witness in Indian civilization is that it never allows religious conflicts to become fully blown religious wars against any religious sect. The basic underlying dictum that has emerged from this understanding is enshrined in the Vedic statement that the one Truth is perceived in various ways” (pp. 485).

The Samanvaya with Sikh Panth is discussed, in the backdrop of separate Sikh religious identity emerging in independent India; the Akali Dal; Punjab terrorism; the 1984 anti-Sikh riots and the later developments. The author points out how RSS consistently shielded and protected the Sikh victims of the riot violence, even when its own cadres were attacked and killed by terrorists before (pp. 488-191). The Samanvaya process with non-Indic religions of Judaism, Islam and Christianity is taken up next.

The author analyses the Hindu-Jewish interactions in both spiritual temporal domains in a scholarly fashion. The position of Hindu leaders from Gandhi to Savarkar on the question of Palestine, Jewish homeland and Zionism are studied with critical lenses.

The saga of ‘Jam Sahib’, a Hindutvaite and saviour of persecuted Jews in the 1930-40s and his role in the Somnath temple reconstruction is highlighted. The natural bond that is spoken of in the India-Israel relations is outlined with a fine quote from Prof. Nathan Katz, “Indigenous peoples develop a unique relationship to the home, unlike what is found in missionizing religions..” (pp. 511).

When it comes to Islam and Christianity, the author charts a course describing the Samanvaya process in all earnestness, but without losing sight of the aggressionist and proselytizing nature of these religions and their track records on terrorism and conversions in the Indian context. But the imperative is certainly on chronicling and presenting the positive and constructive encounters of Hindutva with these religions.

Thus, both the bright and dark sides of Sufism are brought out, differentiating warrior Sufis and mystical Sufis, but also documenting how there was always a link between both groups because of the common religion and the common patronage by the Muslim rulers.

There is an unbiased and empathetic evaluation of emperor Akbar recognizing his change of heart and liberal outlook, but the author credits it to the Hindu influences rather than Sufi influences (pp. 516).

The detailed treatment of Darah Shukoh, with extensive references from the two-volume biography of him by Dr KR Quanungo makes an enlightening read (pp. 520-532). “This is what makes Dara Shukoh important. Had he converted to Hindu Dharma he would have chosen the easier path. But he actually created within Islam a space for the Muslims to understand Hinduism and enrich and deepen their own spirituality through that understanding. In this he made the nondual unity of the Upanishads, which he strove to discover and did discover in diverse traditions, the basis. Thus, one can say Dara Shukoh represents an important civilizational peak for India. And in him there is a model for approaching Theo-diversity for Abrahamic religions—particularly Christianity and Islam”, writes the author, showering totally deserved praises on the great Mughal prince (pp. 524).

RSS openness for dialogue with the Muslim side at every stage of the Ayodhya movement is brought out well. It is significant that this RSS mindset continues till the present, given the fact that Islamism and the Jihadist networks have spread widely across India since then, as the book points out (pp. 537-572).

The account about Syncretic Mysticism of Tamil poets like Kunangudi Mastan Sahib is quite important in terms of history and in the Samanvaya context (pp. 532-538). But unfortunately, this stream of Muslim spirituality has become near extinct in Tamil Nadu, as in many other parts of India, which also had similar Muslim Vedantic sage-poets around the same period, like Shishunala Sharif of Karnataka.

With Muslim society receding into the total grip and control of Wahhabi and hardliner leadership, there is little hope for the revival of such mystical traditions, unless there is a miracle.

But then, nothing can be ruled out for an optimist anchored in spirituality. This is reflected in the final part of this section, when the author says this: “Thus, the Hindutva engagement with the Muslims and Islam cannot be categorized as monolithic. It has varied frameworks: from that of Savarkar to Sita Ram Goel, Golwalkar to Balraj Madhok to Malkani to Narendra Modi. The approach cannot be negatively labelled as majoritarianism or as totally harmonious.. While in the era of internet, the Hindutva school of Sita Ram Goel got traction, on ground the RSS school has more appeal and practical possibilities. In fact, the success of such an RSS appeal to Indian Muslims will also make the Sita Ram Goel school mellow down. Without expansionism and Islamism, Hindutva has almost neutral or even positive relation to Muslims in India” (pp. 576).

Coming to Christianity, the author first describes the approaches that Christianity takes towards Hinduism, all aimed at large scale conversion of Hindus and eventual domination of Christian religion and destruction of Hinduism. Whether it is the soft approach of appropriation of Hindu symbols and practices through inculturation or the hard approach of engineering violent ethnic conflicts and insurgency or the middle approach of using a political proxy war, the final aim is the same, points out the author (pp. 577).

The first approach, which is more complex and nuanced, is dealt in a very detailed manner, with the case study of Shantivanam, a Catholic “Ashram” and the three generations of missionaries who built and grew it. A common reader is bound to get astounded, bewildered and at times amused at the sheer brazenness of the tactics and strategies employed by these missionaries that remain hidden under the cover of the sophistry and pretentious gentleness that they display outwardly.

From secretly conducting Christians mass at prominent Hindu holy places to openly stealing the Hindu religious terminology and texts, nothing is spared (pp. 577-608). The other approaches are outlined briefly. The brutal face of Christian terrorism is highlighted through the NLFT terrorism against Jamatia Hindus in Tripura and the murder of Swami Lakshmanananda in Odisha. The complete chain of events and the background of these incidents is explained in context (pp. 611-619).

The interaction of Sri Ramakrishna movement with Christianity based on its Vedantic high ground is highlighted as a fruitful example of the Samanvaya. While this is factual, the author seems to endorse all kinds of exaggerations put up by the writers of the Ramakrishna “Gospel” and the later day monks of the order, like the “mystical experience of Sri Ramakrishna” meeting a “bearded figure” etc (pp. 620-621).

This is uncalled for, as Hindutva scholar Ram Swarup has already demystified such claims thoroughly in his writings. Hindutva initiating a Samanvaya process is always desirable, but not through obfuscation and certainly not at the cost of peddling self-defeating narratives, this reviewer feels.

In the cases of Thomas Merton, who wrote the preface for the Bhagavad-Gita commentary by ISKCON founder Swami Prabhupada and Thomas Berry, the historian of world religions, both Christian theologians, “one finds how the Hindu-Christian interaction without the agenda of proselytization and appropriation can creatively and spiritually benefit humanity”, says the author, giving the analysis of their works (pp. 638).

Two more glorious examples of Indian Christian priests are given, Fr Anthony De Mello and Fr Anthony Elanjimittam to show the Samanvaya process in action. The former priest was a spiritual celebrity during his lifetime and genuinely engaged with Hinduism respecting the boundaries, but his legacy was quietly buried, and his works were silently censured by the official Catholic Church.

The latter priest, a true Gandhian, was the one who famously coined the term pseudo-secularism and wrote a prophetic book portraying RSS positively, the first English studying the Hindutva movement. Both these illustrious lives, largely unknown to the public today in India, are given due place in this book.

Such a high admiration for Dara Shukoh as mentioned above and such sincere and honest urge to meticulously present real-life examples of positive Hindu-Christian interactions. This is not just some flowery writing to create an image for Hindutva, but the author really means it, in all seriousness.

I am not sure how many of the keen and observant readers of this book would take note of that sentence under ‘Acknowledgements’ in the beginning of the book: “My wife, Fontia Daniel Neelakandan, my son, Shukoh Neelakandan, and my daughters, Shuptah and Shubruh, have been my greatest supporters in writing this book”, and would correlate that with these Samanvaya themes.

Just imagine a youngster giving the background to the name Shukoh to his curious friends and strangers and explaining why his parents named him that way. And you get the idea of how intensely Aravindan has internalized and assimilated the grand ideas articulated in his thesis.

***

The two middle chapters on Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Hindu Sanghatanists before the Sangh provide dense historical material on the evolution of the modern Hindutva movements. This can be thought of as a continuation of the narrative set in the phenomenal book Decolonizing the Hindu Mind by Dr Koenraad Elst and the two great books on RSS by Anderson and Damle, while supplementing them with more new data and perspectives.

The author questions the validity of “anti-intellectualism” charge levied upon the Sangh Parivar by the Sita Ram Goel – Elst school of Hindutva, while fully appreciating the great contributions from that school.

He critically re-evaluates the intellectual discourses of Sangh veterans like Deendayal Upadhyaya, Dattopant Thengadi, HV Seshadri and KR Malkani and convincingly establishes that they were truly remarkable and impactful, contrary to the popular opinion created.

He further presents a case study of Manthan, a magazine of the 1980-90s to prove the intellectual churning process within the RSS. But the fact that this high-quality magazine became defunct after that period due to some reasons, instead of continuing and reinventing itself in the Digital and Internet era is a sad commentary. “Unfortunately, even with the Hindutva sympathizers, the stereotype image of the Swayamsevak as a kind of muscular, non-cerebral automaton persists. A deeper look shows that with no State support or support from extra-territorial agencies, the thinkers from the Sangh, usually spending most of their times sleeping on railway platforms and working among some of the most marginalized sections of the society, evolved an intellectual tradition, unborrowed from Western academia and socio-political philosophies but rooted in Indian soil”, concludes the author (pp. 403). No true Hindutvaite can disagree with this empathetic and realistic evaluation.

The chapter on the “Lives, Controversies, Values and Visions” of four pre-Sangh Hindutva icons – viz. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Lala Lajpat Rai, Lala Hardayal and Bhai Parmanand is another gem in this book. In fact, Madan Mohan Malviya also belongs in this galaxy, and he is referred to at multiple places in the book, though not made part of this list.

This chapter “shows the historical roots that lead up to the space for the presence of Hindutva’s own left wing within the Hindutva universe which makes it difficult to classify Hindutva as ‘right-wing’ proper”, notes the author (pp. 211). This is a very important and much needed perspective, which even many Hindutva insiders are ignorant and confused about.

***

Having followed Aravindan’s writings for close to two decades, both in English and Tamil, I can say this book is a consolidation of the many profound and overarching ideas, themes and insights that he had conceived and expressed through his articles, talks and interviews over the years. These are not just based on his deep research and study but are shaped by the grassroot level understanding of the Hindutva movement and the Hindu society.

It is notable that Kanyakumari, his native and place of residence is one of the most communally sensitive districts of India that witnessed rampant conversions and Hindu-Christian conflicts till a few decades back. All this together has played a role in contributing to his unique thought-patterns and insights.

It would not be surprising if some readers find that the book packs “encyclopaedic” material that can easily expand to three full length books, a trilogy. But I think that Aravindan has intentionally structured and presented it this way so that the framework is grasped and discussed in its entirety, instead of bits and pieces which might lead to speculations and ambiguities. As a result, what we have got is a masterly work that deserves to be called a Hindutva classic.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest