Culture

Subaltern Resistance To Islam And Prospects Of Dalit-Muslim Alliance in West Bengal

- The point of departure for Jogendranath Mondal came in 1950, when his own caste members were attacked by Muslims in his home district of Bakarganj in East Pakistan.

- In West Bengal, he associated himself with active politics and espoused the rights of the lower caste refugees from East Pakistan.

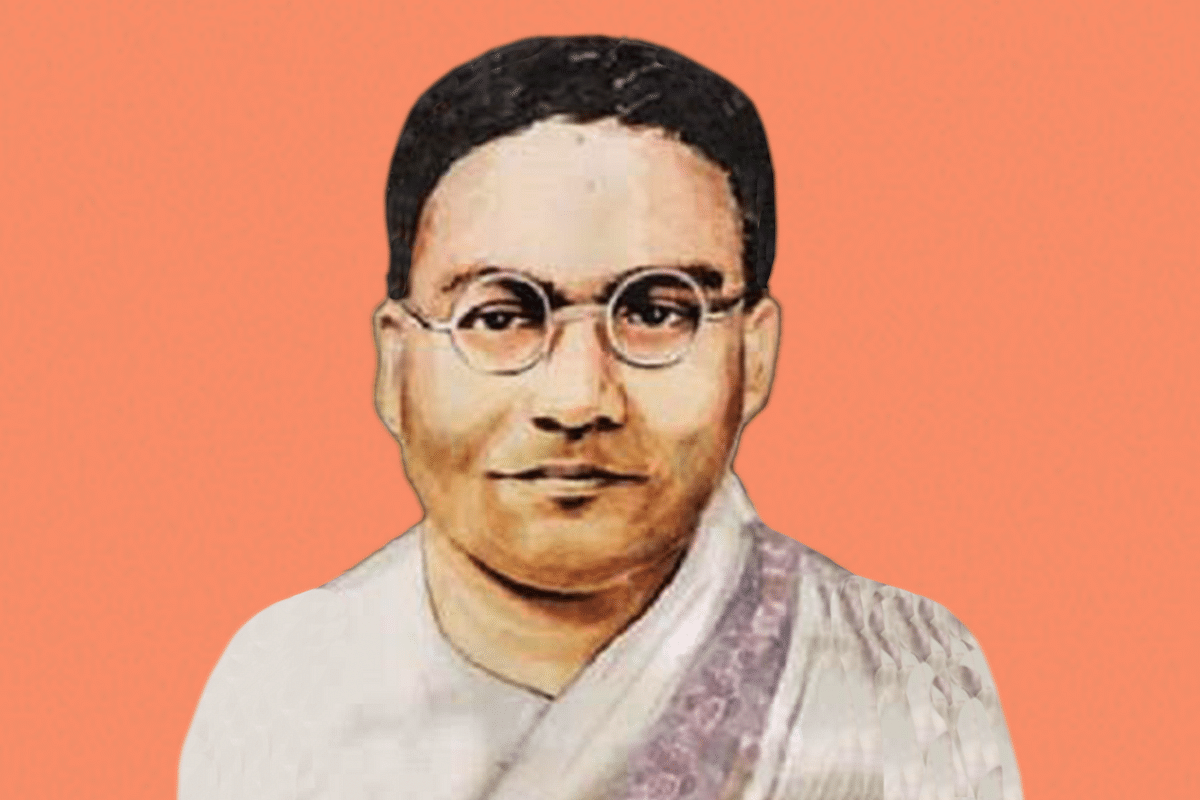

Jogendranath Mondal.

Today, 8 October, marks the day when Jogendranath Mondal, the only Hindu minister in independent Pakistan’s first Cabinet, tendered his resignation and returned to India.

At the time of Partition, Mondal was swayed by the assurances given to him by Muhammad Ali Jinnah that the interests of the seven million scheduled castes of Bengal would be taken care of in the Islamic state of Pakistan.

Mondal, a Scheduled Caste leader and trusted aide of Dr B R Ambedkar, joined the Liaqat Ali ministry as the Minister for Law and Kashmir Affairs.

Mondal was one of the staunchest proponents of Dalit-Muslim unity in Bengal. He advocated such a social coalition based on the premise of a common economic background. But within days of assuming office in Pakistan, he realised the folly of his decision and was disgusted by the anti-Hindu biases of the Muslim League government.

Regardless of caste, Bengali Hindus were subjected to the phenomenon of "othering", as Sekhar Bandyopadhyay puts it, within the new Islamic nation. Being the only Hindu minister in the cabinet at this crucial juncture, Mondal was espousing the rights of the Scheduled Castes, on the one hand, and the aspirations of the larger Hindu cause, on the other.

Mondal had dissuaded the Scheduled Castes from participating in anti-Muslim riots as he believed that the Congress was ‘using’ them for petty political motives.

The point of departure for Mondal, however, came in 1950, when his own caste members were attacked by Muslims in his home district of Bakarganj in East Pakistan. He voiced the interests of persecuted Bengali Hindus before the government but to no avail. He was upset at the indifference shown towards him and his co-religionists in East Pakistan.

In order to evade arrest, Mondal tendered his resignation as minister and returned to West Bengal as a refugee.

In West Bengal, he associated himself with active politics and espoused the rights of the lower caste refugees from East Pakistan. Mondal was largely unsuccessful in making a dent in Bengal politics. He lost every election he fought and died in 1968.

His dream of a common strategic alliance of the Dalits and Muslims did not endear him to the mainstream, nor did it fructify.

The relationship between Dalits and Muslims has been one of both cooperation and conflict since the advent of Islam in Bengal. This article will give an account of Bengali Hindu Dalits, who offered resistance to the Islamist designs in Mondal’s home province.

Subaltern Resistance To Islam In Mediaeval Bengal

Resistance to aggressive Islam in Bengal in the mediaeval period was provided by the so-called subaltern and lower-caste Hindus like the Bagdis, Poundras and Tibars, who exerted considerable influence in the Bengal polity. We shall examine the episodes of resistance one by one.

In the aftermath of the Islamic month of Ramzan in 1375 CE, the Sultan of Delhi, Giasuddin Balban, had sent a large Islamic army to occupy the vast expanse along the Hooghly-Bhagirathi river in Bengal.

This region was ruled by various subaltern communities like Bagdis, Poundras, Koch-Rajbongshis and Kaibarttas. The sultan was determined to crush the dominance of these Hindu tribes and establish Muslim rule over the region. The Islamic armies were accompanied by the Alis who were Sufist Darbesh, tracing their ancestry to the Sayyids of Arabia.

The region around Furfura Shariff, the second-holiest Islamic pilgrimage centre for Bengali Muslims, was known as ‘Ballia-Basanti’ during the rule of the Bagdi Rajas, who were sovereign overlords. This place is still known as Bagdi-Rajar Gor (Fort of the Bagdi Lords). They were related by blood to the rajas of Pandooa and the maharajas of Mallabhum. The Sufi sultan Hazarat Shah led an army towards Pandooa and another army led by Hossain Bukhari marched in order to wrest Ballia-Basanti from the Bagdi rajas.

The two Muslim armies plundered Hindu dwellings and looted and desecrated temples along their march to Pandooa and Ballia-Basanti. They were resisted by the Bagdis, led by local sardars who fought courageously and they soon outnumbered the Muslim invaders.

However, the Alis were shrewd diplomats and warmongers who had a distaste for the ethics of war. They were adept in spreading Islam by the might of the sword. They employed the cruellest of tactics for the sole purpose of wresting the regions from the Bengali Hindu rulers.

The Bagdi Raja, Gopala fought with utmost chivalry yet failed to rescue his kingdom from the invading Alis. He decided to seek refuge under Malla suzerainty and marched towards Mallabhum.

At this juncture, the Bagdi militants faced the Muslims in Kabandhamari and resisted them while they attempted to deter the journey of the Bagdi Raja to Bishnupur. The Bagdis fought with exemplary courage. They lost in both Ballia-Basanti and Pandooa, but in the process, executed four Alis. The Bagdi resistance to Muslim invasion can be compared to the Thermopolis War or the Fall of Gajpur by the Marathas.

During the reign of Gaudeshwara Hussain Shah, the Koch-Rajbongshis, also known as ‘Tibars’, were sovereign rulers of the territory between Rajmahal Hills and Suti in present-day Murshidabad.

Once, while the mother of Hussain Shah, traversed through the Rajbongshi kingdoms, the Tibars ridiculed her by yelling at her, “Gour Badshahr maa nachon dekhiye jaa” (O Mother of the Badshah of Gour, present your dancing steps before us!) The sultan did not take this insult lightly and launched an attack on the Tibars.

The Muslim army led by Hussain Shah destroyed the forts of the Tibars and desecrated the Hindu temples on their way. They desecrated the holy Jibat Kunda. The Hindu rulers of Bengal at that time declined to offer aid to the Tibars. The Rajbongshi kingdoms were devastated and Muslim rule was consolidated in the region.

History would have been written differently had the Hindu rulers of Bengal sent their assistance to the Tibars in wresting their motherland from Muslim invaders. (The Koch-Rajbongshis are classified as a Scheduled Caste in West Bengal.)

The invading Muslims led by Mobarak Gazi and Kalu Gazi faced stiff resistance from the local Bengali Hindu ruler of Khari Mandal of Pundravardhana Bhukti, Dakshin Rai and his brother Kalu Rai who were Poundras by caste.

The Gazis converted a large section of Poundras to Islam. Dakshin Rai and his mother, Narayani Devi, faced the Islamists and attained martyrdom.

The locals worship Dakshin Rai as a ‘Lokdevta’, or folk deity, and regard him to be an avatar of Shiva who manifested himself in order to protect Hinduism and the Poundras from the scourge of Islamic proselytisation.

The Muslim proselytisers led by Pir Gorachand faced resistance from the Bagdi Raja of Hatiyagarh Pargana, Mahidananda. His sons, Aakananda and Bakananda led the local peasants and fishermen of Bagdi and Poundra communities to face the Islamists. Pir Gorachand was executed and the proselytising mission of the Muslims was foiled in its first attempt.

The history of Bengal is incomplete without a mention of the protracted yet glorious resistance of subaltern Bengali-speaking Hindus to the Islamic invasions, who fought with the utmost chivalry and attained immortality. Decades of leftist adulteration of school textbooks deprived generations of Bengalis of their chivalrous past and heritage.

Now we come to the role played by Jogendranath Mondal throughout the episode on Bengal’s Partition in 1947.

Partition, Jogendranath Mondal And Bengali Dalits

The prime target population of Jogendranath Mondal and his associates were the Namasudras of eastern Bengal. Mondal was of the opinion that the Bengali Namasudras were ‘closer’ to Bengali Muslims as both the communities engaged in the same occupations – ie, peasantry.

The Namasudras also have had a history of challenging the dominance of caste Hindus in the past, evident from the swadeshi movement itself. The Namasudras of Faridpur and Bakarganj had largely endorsed the Partition of Bengal (1905) and turned down the Congress’ call to boycott foreign goods.

Eastern Bengal was the only region where an overtly moderate relationship existed amongst the Bengali Dalits and Bengali Muslims. However, their relationship was frequently interrupted by violent riots. And there are historical reasons for it.

Eastern Bengal was primarily an agricultural society where peasantry and fishing were the primary occupations of the majoritarian population. This region was constituted by a large peasantry, which was fairly divided between the Namasudras, the largest Dalit caste, and the Muslims.

In colonial Bengal, the Namasudras were the second largest Hindu caste, and in the districts of Faridpur, Jessore, Bakarganj, Khulna, Dhaka and Mymensingh, the Namasudras were the largest Hindu caste.

According to the 1931 census, Namasudras constituted nearly 85 per cent of the Hindu population in these six districts. This fairly organised character of the Namasudras enhanced their capacity to articulate protest movements, which culminated in the Matua Mahasangha’s self-respect movement (1872-1937).

The perpetual state of cooperation between Namasudras and Muslims has to be seen from an economic perspective.

Both the Namasudras and the Muslims were tied to land. It is obvious that any peasant community would avoid entering into conflicts with a neighbouring peasant community for the sole reason that such conflicts lead to large-scale destruction and displacement of property.

Such aberrations arising out of communal skirmishes often endanger the livelihoods of either or both the communities whose primary source of income is derived from tilling the land.

Also, the Namasudras and Muslims were employed under a common institution, viz. the zamindari system, which was dominated by caste Hindus and Ashrafi Muslims.

However, the relationship between the two communities was equally one of conflict and competition. During the reign of Pratapaditya Bhuiyan, the last Hindu king of Jessore, the Namasudras had joined his forces in offering resistance to the invading Mughal army led by Raja Man Singh. Pratapaditya had an armed contingent of Bahanno Hajar Dhaali (52,000 armoured men) that comprised Namasudras.

The struggle between Namasudras and Muslims for land is a historic one. Often minor verbal skirmishes or sports between Namasudra and Muslim children would lead to violent riots. The communal violence between Namasudras and Muslims in Gopalpur in 1906, at the height of the swadeshi movement, and in Padmabila in 1923, were evidence of the deep-seated fissures within the East Bengali peasantry. Often economic cooperation was marred by communal conflicts.

Both the Hari Lilamrita and Guruchand Charit, the two foundational texts of the Matua Mahasangha, extol the chivalrous heritage of the Namasudras. Harichand Thakur, the founder of the Matua Mahasangha, the religious movement to which the majority of the Namasudras adhere to, was born as a Namasudra who were then known by the pejorative slur of ‘Chandal’.

Widely regarded as ‘Purnabrahma’ (Complete God), Thakur’s ‘earthly descent’ amongst the Namasudras swayed them away from Islamising influences. Thakur was able to offer an independent and alternative space to the Namasudras, away from both Islam and Brahminical Hinduism, but closer to 'Dharmic syncreticism', an admixture of pre-Vedic Kaumadharma, Sahajiya Buddhism and Vaishnavism.

The Guruchand Charit is replete with vivid descriptions of the two incidents of communal violence between the Namasudra-Matuas and the Muslims in Eastern Bengal. Guruchand Thakur, the second Sanghadhipati of the Matuas, often addressed Namasudras as ‘Bir Jaati’ (brave race) and called for resisting any attempt to denigrate their collective honour.

When the Bengali Bhadraloks were agitating for a separate Bengali Hindu homeland in West Bengal, Jogendranath Mondal was supporting the Pakistan demand. He had previously received assurances from Jinnah that the interests of the Scheduled Castes would be taken care of in the new Islamic state.

As a reward of his loyalty to the Muslim League, he was awarded a major cabinet portfolio in the first cabinet of Pakistan. It goes without saying that he was erroneously swayed by the deceit of the league. However, this was only one side of the story.

The Bengali Namasudras led by Pramatha Ranjan Thakur and the Depressed Classes Association joined the pro-partition side in large numbers. But as partition neared, they became increasingly concerned about their future in an Islamic nation.

The Great Calcutta Killings of August 1946 that witnessed a faceoff between the Muslims and the lower castes, sealed the fate of Dalit-Muslim unity that Jogendranath Mondal envisaged. At this juncture, Pramatha Ranjan Thakur, the third Sanghadhipati of Matua Mahasangha, left his habitat in Eastern Bengal and migrated to West Bengal after independence along with Matua followers.

Led by Thakur, the Matua-Namasudras reinvented a space for themselves in the newly-established Thakurnagar in West Bengal, more in the spiritual sense than political.

However, the mass exodus of Bengali Namasudras and other lower castes was yet to happen.

Finally the point of departure came in 1950 when there were massive anti-Hindu riots in East Pakistan and the lower castes, of which Namasudras constituted 95 per cent, started flocking to India. A majority of them chose West Bengal and the two districts of 24 Parganas and Nadia absorbed two-thirds of the lower caste peasant refugees.

Despite the monstrosity of the riots, Namasudras did not migrate en masse to India. They migrated in dribs and drabs.

Sekhar Bandyopadhyay offers an explanation to this phenomenon. Communities that have been traditionally tied to land, migrate only at the last moment, when all hopes of survival in their original homeland have been exhausted. The lower castes of East Bengal lacked the required cultural and social capital to aspire for sound living in India.

In the absence of fair compensation for property and goods lost, the lower castes declined to migrate to India. This is evident from caste figures that depict the Hindu Namasudra population in Bangladesh as being close to 33 lakh, and that in West Bengal to be 35 lakh. This homogeneous distribution of the Namasudra population along either side of the border establishes the constraints of an inter-play of historical trends and economic restraints.

However, it must be noted that though the proposal of population exchange between India and Pakistan was declined by our national leaders in 1947, the Bengali subalterns initiated enforced population exchanges, though not on as massive a scale as East Punjab, in the border districts of West Bengal.

The incoming Namasudra refugees evicted the Muslims from their land in Nadia and 24 Parganas and squatted on their properties. This chain reaction was enacted in the 1964 riots as well.

‘Dalit-Muslim Alliance’: Myth Or Distant Possibility?

The Partition of Bengal in 1947 had jeopardised the livelihoods, properties and self-determination options of Bengali subalterns. With the popular request of population exchange being turned down, the 70 lakh Scheduled Caste people of Eastern Bengal were compressed within the newly created state of Pakistan. The soon-displaced Namasudras and Koch-Rajbongshis lost their natural habitats.

With rising Islamic nationalism in play in East Bengal, the Bengali Hindus were subjected to a conspicuous phenomenon of ‘othering’ where a common Hindu identity transcended all pre-existing caste and political affiliations. This ‘othering’ of the Bengali Hindu had a ripple effect in Indian Bengal as well, more prominently after 1950.

With the entry of Jogendranath Mondal in the politics of West Bengal after 1950, the politics of caste assumed a new flavour. The displaced Namasudras lost their spatial capacity to organise and articulate mass protests.

When the Congress government was sending the Scheduled Caste refugees to far-away places like Dandakaranya and Andaman Islands in 1950s, Jogendranath Mondal accused the Congress of conspiring to turn West Bengal into a ‘caste Hindu state’.

Mondal was not successful in mobilising the subaltern refugees because their ‘caste’ identity was subsumed under the circumstantially relevant ‘refugee’ identity.

Being active in refugee politics for some time, Mondal tried to experiment with the ‘Unity of the Oppressed’ that he had long fought for in undivided Bengal. But to no avail. He failed to the extent that he lost all the elections he contested as an independent backed by the Left Front.

With his death in 1967, things were thought to be ‘under control’.

Soon, with the meteoric rise of the Left in 1967 and their coming to power in 1977, caste assumed the cloak of ‘class’.

The Scheduled Castes were pacified with path-breaking land reforms and co-option in the rank and file of Left parties. The increasing instances of communal riots in the state since 2016, coupled with the politics surrounding Ram Navami, have seen Bengali Dalits acting as vanguards of Hindutva to the extent of confronting Muslims on many occasions.

After a period of vacuum, the caste discourse resurfaced in 2010 when the Trinamool Congress reached out to the forerunner of Dalit resurgence in colonial Bengal, the Matua Mahasangha. Matua leaders were co-opted in the rungs of all major political parties, and furnished with electoral candidatures.

The clerics of the Furfura Shariff and far-right Muslim organisations have plans to re-enact the social coalition of Muslims and Scheduled Castes in the build-up to the upcoming assembly election in 2021.

Though the success of this social coalition on the ground remains subject to the constraints of time and the imagination of election analysts, yet ‘caste’ ought to play a major role in shaping the public and intellectual discourse of West Bengal in days to come.

Avik Sarkar is a writer on socio-political issues of Bengal and Bengali subalterns. He is a graduate in political science from St Xavier's College, Kolkata.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest