Culture

Tagore And The Art Of Transcendence

- In freedom’s poetic landscape, as a colossus straddling the multifarious worlds of poetry, painting, music and prose, the artistic corpus of Rabindranath Tagore stands tall. Really tall.

- Tagore’s genius lies in presenting love as the poetic medium of transcendence and hope as transcendence itself.

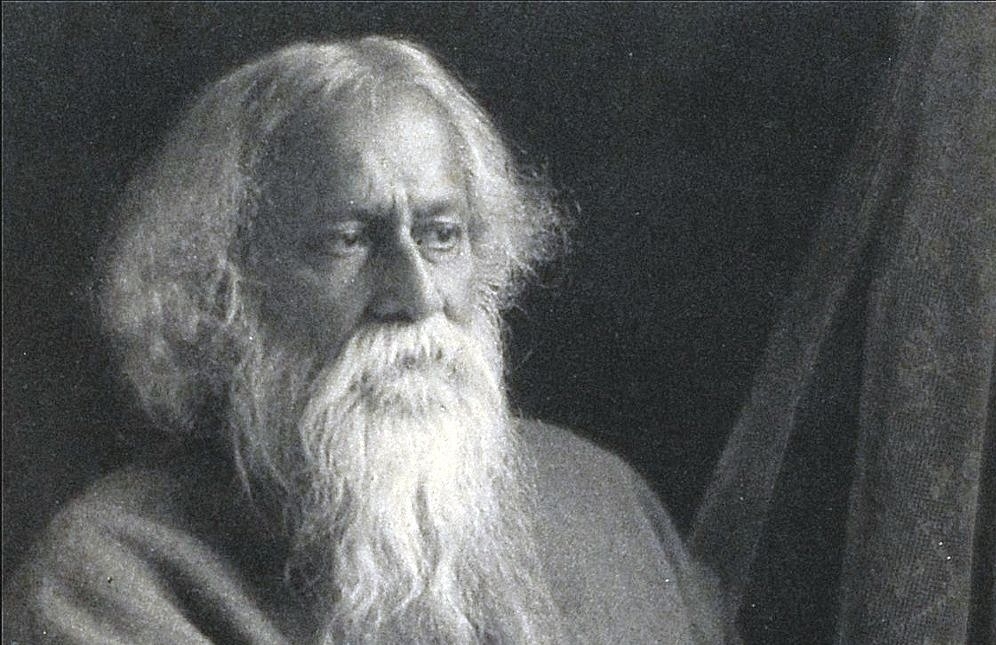

Rabindranath Tagore (Image courtesy Wikipedia)

In my writings over half a year, I have been examining different dimensions of that fundamental entity called "freedom".

Lachit Borphukan, in defending his land from Mughal aggression, embodied with great ferocity, the strong human desire for political freedom. Guru Tegh Bahadur, in choosing martyrdom over conversion, symbolized the inalienablility of spiritual freedom which no tyrant could deprive a man of. Swami Vivekanananda, as a culmination of India's civilizational spirit of freedom, incorporated it into a living philosophy, Vedanta: a dialectical path to freedom through self-realization. And the festival of Holi, exemplifying the humanist foundations of Hindu thought, endures till date as a cultural expression of the childlike innocence of freedom.

Today, I shall dwell upon yet another dimension of freedom: its poetics, or its translation from cosmic heights into our human language of jealousies and insecurities; desires and memories. And in freedom's poetic landscape, as a colossus straddling the multifarious worlds of poetry, painting, music and prose, the artistic corpus of Rabindranath Tagore stands tall. Really tall.

The French absurdist author, Albert Camus, once wrote, "Man is the only creature that refuses to be what he is." This is admittedly the most accurate definition of "man" I have ever encountered. It draws its beauty from the fact that it defines man in opposition to himself but leaves his direction and limits undefined, as if hinting at the infinitude of possibilities that lie open to man, the maker of his own destiny.

In other words, it projects man as a seemingly contradictory, negative-positive, finite-infinite being. The task of an artist, then, is to represent through his art, the tension that characterizes human existence at this twilight zone between the finite and the infinite, when the familiar faces of yesterday stare at the distant-yet-near tomorrow. Preceding Camus by many decades, Tagore's artistic project aimed precisely at such a representation: the constant tension between the "me" that I am and the "that" which I want to be.

In most of his head portraits, for example, the subject emerges from a dark background into faint or bright light. Most subjects stare directly into the eyes of the observer, articulating to the individual a truth of a universal nature. In a few other works, the subject shrouded in darkness, might stare across the observer into infinity, suggesting a conscious presence of an infinite space out there.

The central characters of his classic literary works too are such liminal figures who despite their spatio-temporal limitations, momentarily succeed in transcending the individual human condition to become one with the Eternal Man who alone is the standard against whom we individual beings must measure ourselves.

An illustrative example is Rahamat, the Kabuliwala, who sees in little Minnie, a reflection of his own daughter left behind in Kabul. With this 5-year-old Bengali girl, he forms a beautiful friendship, which is tragically interrupted by his imprisonment. Upon his release after ten long years, when he visits her home in search of little Minnie, to his surprise it is the wedding day of her now-grown-up self. His excitement and longing, though, are brutally shattered when his dear old Minnie fails to even recognize him.

In that flash of a moment, he suddenly realizes the time he has lost in these ten years, along with the childhood of his own daughter he had left behind in Kabul, who too must have grown up to be a young woman like Minnie. And here we, the readers, for once catch a fleeting glimpse of the truth, beautiful in its naked harmony with Tagore's Universal Man. If Rahamat's imagined equivalence between his own daughter and Minnie is an attempt to transcend his spatial limitations, his futile hope that Minnie would remember him is an attempt to transcend temporal limitations.

In another story, The Castaway, we see Kiran, a young upper class Chandernagore housewife desperately trying to transcend the limitations of class and family to give shelter to castaway Nilkanta, who in turn tries to transcend his melancholy condition by seeking the love and attention of Kiran. Although the tale ends on a poignant note of separation, the last scene sees Kiran transcending materiality by throwing an expensive inkstand into the river.

The beauty of such Tagorean transcendence lies in the hope that it encapsulates. Like a Vedantin, Tagore realized early on the complex longings of the human soul. After all, man is "earth's child but heaven's heir". Although "at one pole of my being I am one with sticks and stones, at the other pole of my being I am separate from all."

However, despite this infinite personality of man being his lifelong muse, Tagore did depart from the single-minded focus of the Upanishads on self-discipline and knowledge, looking instead to the Bhagavad Gita for an alternative and more human approach to Reality – through love and devotion – for, "love easily withdraws most of the obstacles that the Self interposes between the contemplator and the contemplated." Tagore's genius then lies in presenting love as the poetic medium of transcendence and hope as transcendence itself.

Nowhere does this element of hope shine brighter than in the art of doodling that he mastered. While penning his compositions, Tagore would often cross out a word or two. Troubled by the sight of these islands of error scattered across his manuscripts, he decided upon their redemption by joining them through lines into beautiful designs resembling different living forms. In his own words,

This makes it abundantly clear that the rhythm of hope is what fuels the dynamism in Tagore's art. Hope, or better still, faith, that the ugly error from yesterday would blossom into a fresh flower tomorrow. It is hope, again, that finally results in man's realization of his own infinite personality, his universal nature. [This could be contrasted with Swami Vivekananda's thought whereby reason is the what drives human intellect towards self-realization.]

Tagore's belief in the universal nature of man did have deep repercussions in the literary world of his time, and continues to subtly influence the scientific world of today. Both, the Judeo-Christian and Enlightenment worldviews that shaped Western Literature, view Man and Nature as fundamentally distinct, if not opposed. This view dominated the writings of almost every major Western litterateur, most notably Shakespeare.

Tagore, on the contrary, once wrote to his niece:

Queer or not, his readers in the war-ravaged West did understand him in the unfolding years and absorbed this refreshing view of the universe, clearly rooted in the Hindu way of life.

Barely three decades after his death, through the work of scientists and philosophers like Rachael Carson and Arne Næss, this conception of nature gained wide acceptance as Deep Ecology. Tagore, in fact, had gone deeper than even the deep ecologists, for, while the latter view man as only interrelated with nature, Tagore saw nature as realizing itself through man! This was a truly revolutionary thought, far ahead of its time.

As the world now descends deeper into a melancholy quagmire of alienation, it is perhaps time to revisit Tagore and transcend our limited selves in a leap of faith, which Tagore, once in his inimitable style, compared with the bird that sings when the dawn is still dark.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest