Culture

The ‘Phantom’ Coda: Will There Be An Apology For The Theo-Racism They Poisoned Our Minds With?

- Directly and indirectly, the ‘Phantom’ comic series furthered a negative stereotype of Hindus. Those who grew up on the comics are today adults.

- Will the publishers of the comics apologise for its content, or at least include a disclaimer in future editions?

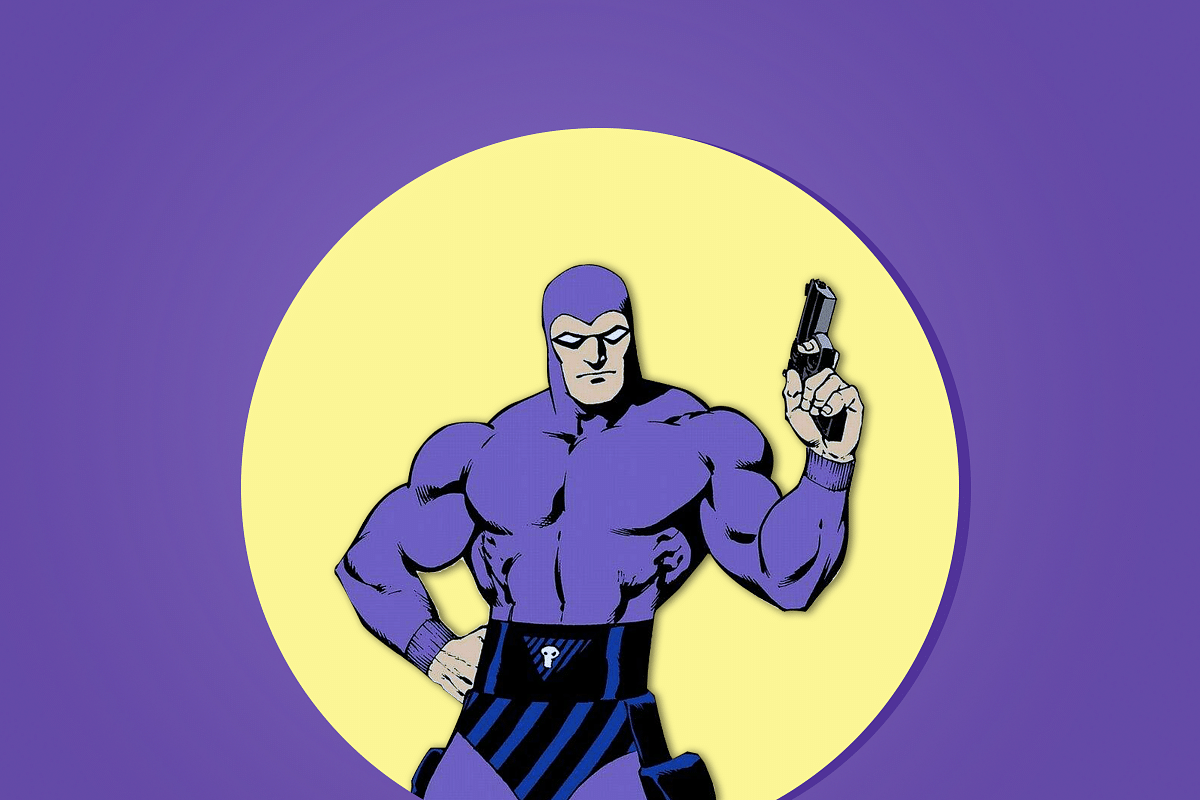

Phantom comics

The outcry against racism is becoming a huge movement. Statues are being toppled. Heroes are being revisited and questioned.

Colonialism acted as a vehicle for racism in most parts of the world. Colonialism also produced varieties of racism. Among these, the skin-based racism is easy to detect and fight against.

There are other forms of racism which can be persistent and escape questioning. They are not predicated on skin colour.

So, it is hard to detect, and still harder to identify the perpetrators of such racism as even racists.

Astonishingly, it is equally harder for the victims to understand that they are victims.

Often, such forms of racism come with ‘civilising missions’. A prime example being theo-racism.

Theo-racism involves hatred for a form of worship and considering the adherents of that particular spiritual tradition as inherently deficient.

Consequently, it is posited that they need to be brought to the ‘true path’.

This makes one form of belief system appear superior to another.

Here, in this piece, a particularly effective form of dissemination of theo-racism is brought out. This dissemination happened in the post-colonial period and the targets happened to be innocent and impressionable children and teens.

For the kids growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s in urban India, Indrajal Comics (IC) (1964 to 1990) have been an integral part of their childhood and early teens. Most probably, there are still adults who are hooked to these comics.

Indrajal comics brought to Indian kids 'The Phantom', a masked fighter of evil and injustice created by Lee Folks in 1936. The children grew up with these comics which imparted their own values invisibly and subliminally. That these values have at their core theo-racism would never dawn on readers, except for those who also had to participate in the resistance to expansionism of monopolistic religions.

For many Indians (this author included), initially, the impression had been that the events in The Phantom series occur in Africa.

However, in reality, they are shown as happening in India.

One of the earliest issues of Indrajal comics not only made it clear that the evil pirates whom Phantom fights throughout history, generation after generation, are not only Hindu but that the traitor responsible for the death of the previous Phantom was one ‘Rama’.

Rama, in the issue, double-crossed everyone who trusted him.

One would think that that was just a name. Naming an evil double-crosser Rama may be just a coincidence. But when placed in the overall Phantom ‘universe’, the name acquires a special significance.

IC number 32 is ‘Oogooru — the murderous deity’.

Dr Axel, is the good white doctor who serves the ‘native’ people with modern medicine.

The ‘native’ witch doctors are angry at Dr Axel because his medicine has made their reputation fall. The youths no longer respect them. They want their people to come back and worship their ancient gods.

So, they conspire to attack and kill Dr Axel. They challenge the ‘Phantom’ who stands between them and doctor. They challenge him to confront their god — an idol that spits fire through simple tricks.

This idol is ‘Oogooru’.

The Phantom, using a mixture of modern technology and his own prowess, shows himself to be immortal to the ‘natives’ and more importantly, smashes the idol of ‘Oogooru.’

Almost quarter of a century later, we find IC returning to the same theme.

This time it is even more improvised. Titled ‘The Conspiring Witchmen’ (Vol.25 No.22), here, the religious leaders of the indigenous traditions try to poison and kill a democratic leader of their own people — a West-educated, non-white leader because he favours Western medicine over the indigenous during an epidemic.

It is quite interesting that ‘the Phantom’ smashes down idol after idol of the ‘native’ faiths.

IC number 67 is ‘Phantom and the Sea God’.

Here, a coastal tribe worships a god that is half-fish and half-man. That it is a ‘superstition’ and that the all forest tribes have a ‘superstition’ each is implied in the very first panels of the comics.

Then, Western gangsters use this ‘superstition’ to rob the coastal community of their valuable pearls.

After ‘Phantom’ thwarts those attempts and proves that the person who was impersonating the deity was a white crook, the idol of the half-fish/half-man god is destroyed by the very people who worshipped that deity.

Note the panels from this issue shown above.

The Phantom with the ‘White Man’s burden’ tolerates the ‘native superstition’ as long as the tribes respect the ‘Phantom peace’ — the colonial order, which in post-colonial age becomes the Western religious ethos.

Note also the suggestion of using the pearls which the tribe believes as belonging to their deity, to buy the speed boats.

And then the deity-impostor, a Western criminal, is arrested by the Phantom and the result is that the tribe throws away their deity and accepts to use the sacred pearls to buy speed boats.

IC No. 87 is the ‘Legend of the Durugu’ which again tells the story of an idol of an ape-god whose worship the Phantom had forbidden in order to create peace in the jungle.

He had also thrown down the gigantic ape-god idol.

However, a ‘native’ finds a gigantic white wrestler who in an ape-outfit claims to be the idol-come-to-life. With this living ape-idol, the scheming ‘native’ scares the ‘superstitious natives’ and challenges the Phantom. Of course, the Phantom exposes the fraud after defeating the living ape-god idol and peace returns.

The Phantom comics also cultivate a strong aversion for the religious marks on the forehead.

Not only the traditional shamanic villains display the ‘U’ or ‘V’ shaped symbols on their foreheads but also some long-standing Western criminal cults sport bald head and ‘V’ shaped mark — ostensibly to imitate bald-headed eagles, yet having a strong resemblance to ISKCON which was then gaining a foothold in the West.

The 'Phantom’ is called the ‘Guardian of the Eastern Dark’ by the ‘natives’. This again refers to a human-sacrificing, idol-worshiping cult of drug-pushers, which the Phantom destroys.

Like ‘Singh pirates’, this cult is also an enduring generational enemy of the ‘Phantom’.

This particular comics issues (IC No. 319 & 320) are quite amusing for the way they repeatedly show the gruesome human sacrifice as a ritual associated with idol-worship.

Here, the skin-colour based stereotypes are altered in a different way. The ‘Eastern Dark’ cultists are fair-skinned idol-worshipers.

These non-European, fair-skinned people raid the dark-skinned ‘native’ villages for human sacrifices to be offered to their deity Zaal.

The deity is multi-armed and there is always a fire inside the belly of the idol into which the priests throw the dark-skinned victims.

The ‘natives’ by themselves are powerless to fight this evil.

Of course, the Phantom fights them.

As usual, he topples the idol and makes it go to sleep.

Two hundred years later, the present Phantom would come and finish the job of his ancestor. In two hundred years, the human-sacrifice slave-raiding cult has transformed itself to become a drug-peddling one.

In the case of drug peddling, we see a clear and explicit stereotyping of Hindus.

A criminal drug peddler makes jungle youths addicts to drugs and uses them for robbery.

This can be considered as the ‘Phantom Coda’ of Western encounter with non-Western cultures and traditions — particularly Hinduism.

The writer remembers (though could not locate now) one cartoon in the Western media, showing Vajpayee as similar to this particular Zaal image and titled ‘Shiva’ in one of the Western magazines in the aftermath of Indian nuclear tests.

Perhaps, Hindu scholars should start studying the psychology of both the Western observers of Hindutva and their Indian-born, PhD qualified academic informants — there is a strong possibility of the unconscious influence of the ‘Phantom’ comics.

One can see how the native white, idol-worshiping priesthood making slaves of the dark-skinned natives who in turn are to be freed and protected by the Phantom maps neatly to the myth of Aryan Brahmins initially massacring and later enslaving dark-skinned natives.

The Phantom also fights against secular criminals, tyrants, swindlers, muggers etc. He is also romantic. Thus, the anti-idol-worship and anti-indigenous-traditions streams which run throughout the Phantom comics with decades of consistency come in an attractive package.

So, they seep in effectively into the minds of the impressionable pre- and early-teens.

The ‘good natives’ are the ones who side with the Phantom, who is symbolic of Western colonialism in its benign form.

By nature, the ‘natives’ are ‘superstitious’ but they can become rational and good by Westernising themselves.

‘The Phantom’ is the brave mid-wife of this process.

Those who resist it are usually the priesthood of the ‘natives’.

They are clever exploiters who have a vested interest in protecting the ‘native’ religion.

Though seemingly set in Africa, that the villains in the ‘Phantom’ universe resonate mostly with the only living non-monotheistic culture of diverse spiritual traditions and theo-diversity, the Hindu Dharma, is not an accident.

In Tintin comics, we see these days a disclaimer in titles like ‘Tintin in the Congo’. It runs:

One wonders if for Indrajal Comics, its original owners, The Times of India would make a similar statement regretting importing into India such openly Hindu-phobic comics.

Will those who continue the Phantom comics now also make a similar apology to living Hindu Dharma and its adherents for such negative inhuman stereotyping of idol-worship and indigenous knowledge systems?

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest