Culture

Tradition and challenges

Mandolin Shrinivas was an Indian classical musician who excelled in world music. But he is a rare example. What are the obstacles Indian musicians face, and how does their success story read?

One person is speaking in German, the other, in Italian. In front of them is a group of listeners, very few of them familiar with both—or perhaps even either of—the languages. But they understand the essence of the conversation. Is that possible?

Relocate the context. Trained in Indian classical music is a gifted performer who creates a composition with his counterpart from the disparate worlds of jazz, rock, or Western classical. The result is a diptych of seamless artistry.

Onstage, their conversation in two different musical languages gives rise to a third language that has a connect—and yet no connect—with conservative knowledge of grammar. This third language communicates with the listener because the outcome isn’t defined by tradition. With its freedom-seeking character, it conjures up an atmosphere of harmony which everyone can sense and enjoy.

U. Shrinivas, who passed away yesterday, will always be a key turning-point figure for reasons beyond his mastery over Carnatic classical music. Firstly, he played the mandolin, an instrument typically associated with the West. And he took it into that rarefied space where music knows no cultural boundaries.

He worked with many artists, among them eclectic guitarist-composer Michael Brook and guitarist John McLaughlin. Collaborating with McLaughlin is a big challenge, the artist having mastered different genres of music right from jazz to psychedelic rock. He is the quintessential adventurer who glides from one form to another with the sort of ease no other guitarist has ever matched. Shrinivas had worked with him. He had worked with others, too. His take on, and interpretation of, music was as unique as the instrument he played.

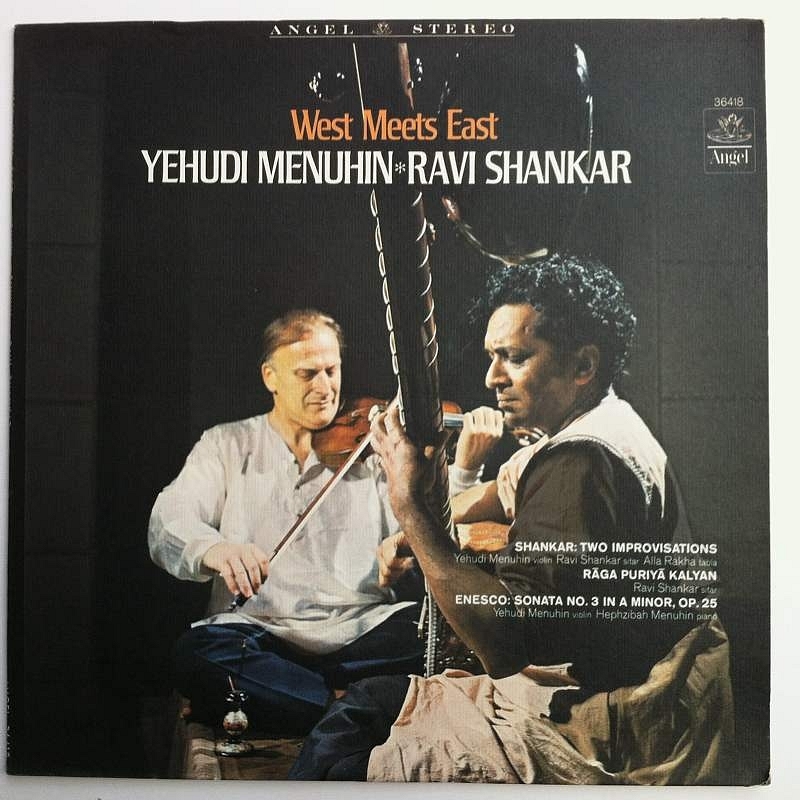

Most Indian classical musicians who venture towards new territories need courage. Endeavours to do away with constrictions is difficult because of the environment they are brought up in. Pandit Ravi Shankar began the process of change. Having realised that an instrument must not be limited to its usage in a specific idiom, Shankar began his quest for discovering new areas by working with master violinist Yehudi Menuhin and jazz saxophonist John Coltrane in the mid-20th century. His search for a new kind of purity led to classics such as the chamber music album Passages with the minimalist American composer Philip Glass.

Shankar’s most frequent accompanist on the tabla was Ustad Alla Rakha Khan whose nimble fingers on the tiny drums mesmerised John Densmore of The Doors, which he mentioned in his autobiography Riders on the Storm. Densmore was not an adventurous drummer. What made him respond to Khan? Being a musician first and a drummer only thereafter, he had reacted to the complex rhythm structures which Khan’s fingers created so effortlessly.

That Indian expertise, if incorporated within the larger framework of international music, can enrich the form of art itself has been proved by others. Had he played longer, Shrinavas might have come close to the stature of L. Subramaniam whose violin has spun endless yards of melody to create epics with jazz violinist Stephane Grapelli and jazz keyboardist-pianist Joe Sample among many others.

Khan’s son Ustad Zakir Hussain has had a glorious career. Ghatam maestro Vikku Vinayakram and now his brilliant son L. Selvaganesh who plays the kanjira, and Subramaniam’s brother violinist L. Shankar who is well known for forming the band Shakti with McLaughlin are part of the lengthening list of those who are taking this tradition forward.

Compared to Ravi Shankar’s era, the percentage of purists that questions the ‘dilution’ in the music of the intrepid seeker has lessened. However, the disciple is usually confined to learning patterns of notes, thousands of them, whose distinctive identities classify their existence in classical music. To be able to ignore the closed minds of those who want them to adhere to their specialised form isn’t easy. The ability to appreciate crossover music is the second, which is more difficult than it sounds because many classical musicians are happy to play within their comfort zones.

This is ironical because excellence in classical music is dependent on the resilience of the artist. If a spontaneity-driven performance—which Indian classical music is—fails to look beyond the obvious, the artist is lost in a huge crowd. The handicap for these quality performers therefore is a psychological one which grows because society as well as the gurus train the mind to think in one direction.

Then comes adaptability. Diversity in jazz is undeniable. Blues branches out in many different directions. But when a jazz musician performs with a classical musician, how can one retreat from the limelight to give space to the other? Which is that portion where both of them can combine their two diverse styles? When would a classical instrumentalist try to innovate with a segment that a jazz performer creates and vice versa?

Such questions must be asked and answered repeatedly in concerts where the composition’s theme is reduced to a basic structure. More than one’s mastery over one’s own art form, a musician acquires the confidence to adapt only after he understands the character of other schools of music.

It is true that what we know as world or fusion music isn’t popular in India. But the equally big truth is that some of our musicians have taken their craft outside the shores of the country and elevated it to a high level of acceptance. Having learned to toy with the note structures and rhythm patterns of the compositions they have grown up playing, many of them have understood that making music in a broader sense of the word is possible as well as necessary.

Exporting our instruments with their individualistic sounds, their pitch-related limitations and strengths and unveiling the merits of Indian classical music to the world couldn’t have been easy. Because of insufficient exposure in their younger days, the toughest part for most is understanding, appreciating and merging their styles with others who have evolved from other backgrounds. It is a process of learning, which manifests itself when Zakir’s younger brother Taufiq Qureshi shows us his percussion skills with instruments imported from Africa.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest