Culture

Why Did Buddha In A Traffic Jam Invite Left-Lib Anger

- Apparently the so-called “Hindu right” were supporting Buddha in a Traffic Jam (BITJ) while a lot of the Indian Left chatter was in opposition.

- This violent polarization about the movie is strange. BITJ is hardly a propaganda film, by any account.

- If you were to read the horrified reviews from Rediff to Huffington Post to Scroll.in, the movie is “a propaganda film”.

- Data by independent bodies such as the Global Terrorism Database and the South Asian Terrorism Portal corroborate that Maoist terror is by far the biggest killer in India.

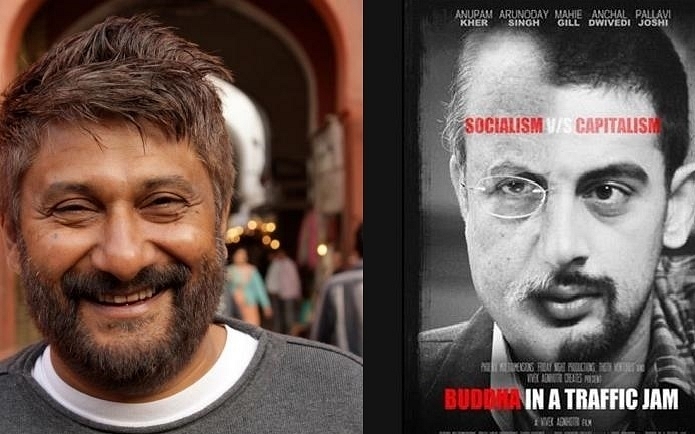

Picture Courtesy: YouTube

The film Buddha in a Traffic Jam (BITJ) was appearing so regularly on my Twitter feed that I had to finally go and see it. I went to see it with family, though my sister, who is a college professor in Delhi NCR, hadn’t even heard of it. She relies on newspapers for most of her movie reviews and selections, and clearly, the movie had not received much coverage in the mainstream press to come to her attention.

The Twitter chatter before the movie seemed quite polarized. Apparently the so-called “Hindu right” were supporting it while a lot of the Indian Left chatter was in opposition. At Jadavpur Univerity, known as a hotbed of far-left activism, the film’s screening was first cancelled by authorities and, later, an open-air screening was violently opposed by a section of students who gheraoed and manhandled the director and script-writer Vivek Agnihotri.

(Warning, some spoilers from the film ahead)

This violent polarization about the movie is strange. BITJ is hardly a propaganda film, by any account. Rather it quite clearly rejects social conservatism, caricaturing those opposed to “women in bars” with a remake of the “pink chaddi” campaign. The story-teller wants to make a relative limited point and support for social conservatism isn’t that point.

The film opens with the scene of a tribal family in Bastar, which is apparently unchanged for millennia. In comes a government official, who pruriently eyes the young daughter while forcing her father to sign a form that he supports Salwa Judum, the counter-naxalite group. Later the naxal group shows up with their own brutality. It even has the government official forcing some “Bharat Mata ki Jai” slogans, strangely out of place in the scene, but remarkably prescient of the 2016 controversies for a film shot a few years ago. Propaganda should be made of sterner stuff.

The story meanders in the first half, setting up the characters and the scene. Vikram Pandit (Arunoday Singh) is a somewhat earnest business school student while Ranjan Batki (Anupam Kher) is his business schools professor, who turns out to be a closet Naxalite. There are vignettes of over-the-top scenes of drunk students and random swear words, some of which were quite unnecessary and tend to give the movie a wannabe feel. If the director was trying to be edgy in these, he did not succeed. Nonetheless, the movie did convey a sense of how certain extreme-Left professors “groom” students to draw them into the “comrade” cause.

Ranjan Batki’s wife runs an NGO that promotes tribal pottery, which unbeknownst to her, is a conduit setup by her husband to funds the violent Naxalite insurgency. When the government turns off funding for the NGO, the entire scheme falls apart. So Batki suggests that Vikram Pandit uses his marketing skills to come up with a new plan.

As someone who has been part of many tech startup ventures I find this part a bit thin. An app is hardly a revolutionary idea, and there is many hurdles to be overcome before something like that can actually succeed in the market. Nevertheless all the assorted comrades get very worked up about the very idea of this, even before it has made any real world impact. In the end the film is a fairly simplistic plea for a disintermediated market-economy to help lift people out of poverty rather than the whole NGO-Naxal-Comrade deal.

Coming as I do from the tech world, I may naively be assuming the obviousness of this proposition. Not that it is a cure-all. The colonial state remains far too intrusive and centralized. But it’s a mild economic-right view, hardly one I’d imagine, that would cause violent protest from JNU to Jadavpur. Yet I may be underestimating the intellectual fossilization of the Indian Left eco-system.

If you were to read the horrified reviews from Rediff to Huffington Post to Scroll.in, the movie is “a propaganda film.” Scroll.in’s Nadini Ramnath says “warnings about the “red menace” … sound like direct quotes from the speeches of Baba Ramdev and Mohan Bhagwat.” This is hilarious, since data by independent bodies such as the Global Terrorism Database and the South Asian Terrorism Portal corroborate that Maoist terror is by far the biggest killer in India, where the so-called “Hindutva” violence is barely a rounding error.

Suprateek Chaterjee in HuffingtonPost calls it a “right-wing propaganda piece”, Raja Sen, writing in Rediff says BITJ “makes me feel sorry for Indian Right Wingers” because it is apparently not good enough propaganda. Sarit Ray, writing in the Hindustan Times, calls it “ propaganda disguised as cinema.”

This commentary is hilarious because it assumes, a priori, that Agnihotri’s film was a propaganda film. It is anything but. My sister, the professor of English, found it very thought-provoking, and she was dismayed by the relatively empty hall. “Such independent voices should be encouraged,” she opined, perhaps because our academic institutes have stilled so much real debate. My mother, who had joined us, was put off by the gratuitous swearing, smoking and sozzling. I myself had expected more, both from the film script as well as its message. I was also turned off by excessive English use made worse by English-only subtitling. Clearly not something aimed at the common audience. That plus an unnecessary A rating, made the film stillborn as a mass film. Though my sister loved it, I thought the narrative was jagged. In the end, the message too was a rather simplistic socially-liberal economic-right view. Free markets and the internet will save us.

I thought the message was obvious a few decades ago with the collapse of totalitarian left regimes and China switching to a market economy. But given the violent reaction from India’s communist-left, and the reviews from left-leaning commentators, perhaps that message has still not penetrated India’s intellectual Don Quixotes. They’re still tilting at windmills of “Hindutva” and “American Imperialism” while collecting NGO-paychecks from Ford Foundation and tweeting on their IPhones. Like Catholic Church Priests aghast at the Protestant reformation, the idea of a disintermediated economy and narrative irks them no end. What could be worse than the Subaltern speaking (when Harvard professors do such a fine job speaking for them) than the Subaltern selling. On the internet. Stalin save us.

The ideologies of the Indian Left would be simply a bad joke, like lawyers wearing 19th century black gowns in the Delhi heat, if left-wing terror in India didn’t take real lives everyday. The story has been that not all of those on the “Left” support the extreme violent murderous Maoist gangs. Yet going by the reviews one would wonder if that analysis is misplaced and Maoist groups do have a fairly sympathetic cheering club among the urban Chaterjees and Sens. Watch the movie, if for nothing else than to see how even a mild critique of their dogmas irks them.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest