Culture

Why I Am A Hindu – Let Ursula K Le Guin Tell You

- Ursula K Le Guin sees how a system like Dharma, if undefended, not just vanishes but vanishes with a tragic loss to humanity.

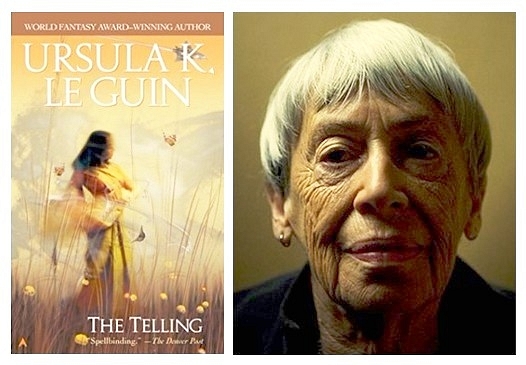

The Telling, Author Ursula K Le Guin

Ursula K Le Guin loved Taoism. Then she realized something. Taoism has almost been abolished from China. A religion, a complex body of religion, that survived for thousands of years was destroyed in a few decades of the ‘Great Leap forward’ under Chairman Mao. It pained and troubled her. She wanted to write about the loss. And she wrote ‘The Telling’ (2000). In her own words:

This novel is important in ways more than one. For Le Guin, the science fiction she writes is more descriptive than predictive. And hence, this novel becomes a deeper description of not only the destruction of Taoism – the natural religion in China by the Marxist state religion but also explores how the expansionist mono-cultural system can hunt down and destroy the natural religion – branding the latter’s organic structures as superstitious and exploitative.

‘The Telling’

The novel centres around Suttee (‘Sati’), an Indian born girl who had lost her lesbian lover Pao (‘Tao’) to a religious terror group. Suttee has grown up seeing how the religion she grew up in, along with other natural religions, was destroyed by a ‘One God, One Truth and One Earth’ religion of Unist Fathers. A global monotheistic theocracy arises. However the religious structure soon falls with the intervention of ancestral aliens federation - Hainish Ekumen (Hainish - Ekumen is part of the larger universe common in the fantasy-scifi of Le Guin). Though Unists do not like Ekumen, the change becomes inevitable. Soon the monolith created by the Unists crumbles and devolves into numerous competing as well as mutually opposing religious terrorist cults - but all rooted in ‘One True God’ theology. Meanwhile democracy returns and Hainish education centres increase.

Suttee is a scholarly product of these institutions in Terra. Now she goes on a mission to another world – Aka – to knowledge-mine their natural religious system and culture. In Aka she discovers a situation that very much resembles the Unist religion eliminating natural religions in her own planet. A singular ideological state is waging a war like inquisition against the natural traditions evolved in the planet. With the knowledge she had gained from her Terra based Hainish education, she tries to comprehend the natural system of Aka and through her eyes the story unfolds.

Through the novel, Ursula Le Quin describes the destruction of natural religions in two planets. Their destruction on Terra (earth) – a thing of the past – surfaces as a parallel and a warning when Suttee comprehends what is happening in Aka. For a Hindu, the novel is both descriptive of her present and a predictive warning about his future.

Problems in Defining Hinduism

One of the basic issues raised again and again starting from colonial Indologists to every modern day Hindu baiter, academic, political or media person, is the inability o define Hinduism. Hence, often they come to the conclusion that Hinduism is an artificial construct. This conclusion is often a starting point for hatred against Hinduism – both psychologically and strategically. At best, their ability to comprehend a non-monotheistic non-belief based system can extend only up to Buddhism. So, in most of the modern day discourses, Buddhism and Chrsitianity/Islam are shown in Western discourses as two major contradictory religions while Hinduism is discounted.

Ursula Le Guin goes to the root of this problem in her novel. When Suttee tries to categorise the Akan system, what she sees is a system that is similar to Buddhism or Taoism.

Note how easily Suttee chooses Buddhism and Taoism. Le Guin critically hints here at the inability of the West to raise above their own comfort-zone categories. So far so good. Clear categorization – what a typical Western anthropologist, even one sympathetic to ‘Eastern’ religions, would end up doing. But then Aka system throws up confusing surprises at attempts of such concrete categories:

It is not hard to identify the beautiful young deity - sometimes a man and sometimes a woman. Suttee soon becomes ‘unhappy with her definition of the system as a religion; it seemed not incorrect, but not wholly adequate. The term philosophy was even less adequate. ‘

In other words, Suttee is wrestling with the same problem as do sympathetic Indologists. By bringing in a girl from a real natural religion, who actually discovers in another planet, her own ancestral religion and yet is at a loss to understand it through the categories of her secular education, Le Guin, perhaps unintentionally, creates a powerful metaphor for what the Indologists are doing to Hindu culture.

Now Suttee ends up calling it 'the Great System’: (reminding one of Hinduism being called merely Dharma - Sanathana Dharma - the eternal Dharma: Esha Dharma Sanathana:) Then she calls it ‘the Forest’, and Le Guin adds enigmatically, ‘because she learned that in ancient times it had been called the way through the forest.‘ : (reminding a Hindu reader of Aaryankas - the forest books or Tagore’s statement that the culture of India has essentially been a culture fueled by forest culture). Then: ‘She called it the Mountain when she found that some of her teachers called what they taught her the way to the mountain. She ended up calling it the Telling.‘ The young observer from Terra discovers:

The most important thing is the sentence that Le Guin adds to this statement enigmatically: ‘ Until, perhaps, the present time.’

As we go through the novel, it becomes clearer that the unfolding story deals with many questions of ignorance which pass for perspective in the Western social sciences and media discourse studying Hinduism.

Does not Bhagavad Gita also promote Holy War?

One such question which pseudo-seculars and also many Western intellectuals ask Hindus is about Gita and Mahabharata war. Is not what happened in Kurukshetra Indian version of holy war or Jihad? And does not Gita also condone violence similar to Koran? Ursula provides an answer in this in her novel:

In other words, the civil wars are not holy wars. The allusion here is clearly to Mahabharata and the irony is again hard to escape. Suttee is studying in another planet an epic and its related sacredness and she is puzzled by the inability of the frameworks she had learned to deal with it. The reader knows that she could have easily understood it had she used the knowledge from her own ancient culture.

Why do Indologists fail to understand Hinduism?

Ursula Le Guin makes a very pertinent observation as to why the colonial knowledge-hunters cannot understand a natural religion (like Hinduism). Perhaps every social scientist who wants to understand Indic culture and spirituality in a holistic manner or for that matter any natural religion and its evolution, should etch these words in every endeavour they make:

If one remembers what the broken mirror piece of colonial Indology did in studying Indian history, culture and spirituality, then one can understand well how the broken mirror not only distorted Indian culture through the Aryan race theory but also cut the very hand that held it with the concept of Aryan race giving birth to Nazi racist ideology killing millions in the West.

So what happened to Hinduism?

Not that Suttee is completely unaware of her ancestral religion. She remembers but only very vaguely. Yet the memories become important in the narration of the tale. She recounts to the ‘Monitor’ of the corporation, the past history of Terra as a warning to what horrible destruction an expansionist monoculture of the mind can bring to a planet. So, she remembers and tells. The meaning of her name and how its layered meanings were taught to her – her uncle explained it to her.

She remembers and tells how varied forms of worship co-existed and how the same individual could easily move between these varied forms of worship and deities:

Then she recounts who the Unists were and what they did to the Hindus:

Suttee was telling all these to an official of the state-religion that promotes the worship of ‘One True God of Knowledge’ in Aka by destroying and ‘reeducating’ the Maz - the traditional system of sacred community who pass on ‘the Telling’. She was hoping that the official would see the parallel. And when she gets to the part of Unist Fathers the official at once draws parallel between the Maz and the Unist Fathers, reminding any Hindu reader of how our own pseudo-secular intellectuals are creating such false comparisons. Suttee of course corrects him pointing out the fallacy in such a comparison.

The Hindu Identity of 'The Telling’

There are several places in the novel where Le Guin leaves the readers with no doubt about the nature of the religious-cultural system she favours. For example, Suttee explores the Aka for sacred literature:

As she struggles to understand the 'the Telling’ of the Maz, whether it is memory or history or belief, she hears the voice of her uncle in the mind:

As Suttee continues to discover what ‘the Telling’ is , what can be a much needed definition of what Hinduism is , arises:

Replace the words ‘on this world’ with ‘in India’ and you have one of the most accurate definitions of ‘Hinduism’. The description of Ursula Guin independently echoes what Sri Aurobindo writes about India’s creativity:

Also it finds resonance with the following words of Savarkar in his paper on Hindutva:

A comparison of the above three passages can show a clear similarity.

Le Guin even brings out a humiliating case of temple destruction in her novel. In Aka there are temples. Again, there is the limitation of language. She does not know if they can be called ‘temples’. But then, under the rule that favoured one God of Knowledge, all their temples had been demolished and so was their most holiest of the holiest ‘the Golden Mountain far to the East’.

The anti-Brahmin hatred in India both shares many similarity and differs from the anti-Semitism. Brahmins are seen as cunning alien Aryans who enslaved non-Brahmins. In this, the parallel between anti-Semitism and anti-Brahminism is very clear. However, the description of Brahmins as the evil priests who exploited the people through religion is part of the larger hatred towards Hinduism. The Brahmins are hated not because they are really alien. They are hated because they are seen(rightly or wrongly) as the custodians of Hindu Dharma. In 'The Telling' a very similar propaganda is made by 'Office of Ethical Purity' of 'The Corporation' that promotes the cult of the one True God of Knowledge.

Just replace ‘the maz’ with ‘Brahimins’ or ‘Hindu priests’ and one can see the passage becoming indistinguishable from a typical Dravidian pamphlet or the anti-Hindu propaganda literature one finds at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Ursula Le Guin with all her deep understanding of the Dharma, its literary aesthetics, spiritual truths and high philosophy also sees the agony of its destruction. She sees how such a system if it is undefended not just vanishes but vanishes with a tragic loss to humanity. Ursula Le Guin sees the the holistic Hindutva nature of Dharma.

We can contrast this holistic understanding even better if we compare it with the highly decorative and partial understanding Shashi Tharoor exhibits in his latest book ,‘Why I am a Hindu’.

Tharoor sees Hinduism as a kind of beautiful exotic flower vase of high philosophy in his drawing room - with no understanding of the sufferings which the generations of Hindus have undergone to protect and preserve it for posterity. He chooses not to see any danger to Hinduism. Having disembodied it from its historic and present context, Tharoor’s Hinduism is more an abstract leisure activity of the affluent than anything else. In ‘The Telling’, with the emphasis on the need to remember this painful past destruction of the Dharmic natural religion, not to seek revenge or harbor vengence but in order to prevent the repetition of similar expansionist annihilation in another planet, Ursula Le Guin emerges as a passionate defender and describer of Dharma. The novel also makes a sensitive and sensible Hindu understand the futility of drawing the artificial line between Hinduism and Hindutva.

If you want to know why you are a Hindu today then read ‘The Telling’.

Also read:

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest